The nascent commercial entities focusing their business plans on the commercial potential of space resources utilisation are operating at the bleeding edge of current space-related legal and regulatory frameworks. Governments are in initial stages

of defining national legal schemes associated

with space resources development, and how it relates to existing international law regarding space activities.

Both the companies and the governments that oversee them find themselves in an environment where political decisions and changes can have significant impacts on the potential economic outcomes of commercialisation of space resources.

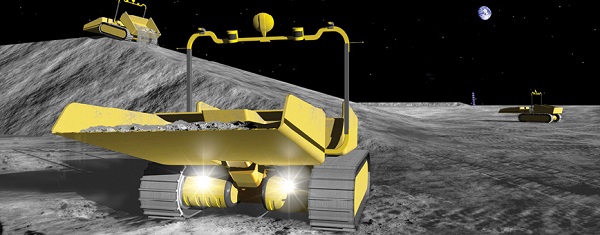

Excavating robots could be used on the Moon to recover water and/or hydrocarbon resources under the topmost layers of the Moon’s surface, potentially yielding material for rocket propellant and life support supplies

Excavating robots could be used on the Moon to recover water and/or hydrocarbon resources under the topmost layers of the Moon’s surface, potentially yielding material for rocket propellant and life support supplies

The environment is characterised by a level of political risk. As Peter Marquez, Vice President for Global Engagement at asteroid mining company Planetary Resources, says: “Every time we’ve had a discussion with investors or potential investors the discussion has not been about ‘is the technology doable?’ The thing that gave them pause was, ‘Can you actually protect my investment?”

Current status

Before discussing policy issues, it is useful to briefly examine the focus of business plans based on space resources utilisation (space mining). Commercial business plans in this area focus on characterising, accessing, extracting, and processing useful materials from natural objects in space. These materials might include both precious and non-precious minerals, as well as volatile gases and water. These resources could potentially be sold into multiple markets and applications, including supporting human operations in space, providing raw material for in-space applications and manufacturing (including serving as rocket fuel), and providing material for production applications back on Earth.

Existing regulatory approaches which were originally developed for communications, remote sensing and space launch services will not be sufficient

At least initially, most business plans are focused on in-space applications for space resources, as both the physics and the economics are more favourable than for transporting resources back to Earth.

Full-scale space mining activities are many years away - those commercial companies involved in the activity are in what is best described as a technology development and capital raising phase. They are testing and proving technology, and may be flying small-scale satellites to conduct prospecting operations - identifying and characterising potential mining targets.

Legislation and access

Like most areas of economic activity, space resource utilisation business plans are based upon the ability to access a resource, produce a product, service, or goods based from the resource, and produce revenue from that product based on established market activities.

An economic system requires a level of regulation and oversight to ensure it functions. Regulation and governmental oversight is part of an overall market framework that provides stability and confidence in validity for commercial entities and those that invest in them. Just as the commercial companies are in the initial stages of developing and validating hardware, governments have begun to establish regulatory and policy frameworks.

US President Barack Obama signed into a law in November 2015 a fairly comprehensive piece of legislation focusing on the development of the US commercial space sector, the ‘US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015’. One title of this law, Title IV - Space Resource Exploration and Utilization, has elicited considerable international attention.

It authorises US commercial entities engaged in the recovery of space resources to possess, own, transport, use and sell space or asteroid resources obtained in accordance with US and international law. In layman’s terms, the Act makes asteroid mining permissible under US law for US entities.

This provision has led many to question whether the US law violates the Outer Space Treaty (OST), the document which represents the primary source of international law governing space activities. At issue is whether authorising the use of space resources violates Article II of the Treaty, which states ‘Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claims of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by other means’.

The most prohibitive interpretation of this Article would suggest all extractive or consumptive uses of space resources on celestial bodies would be prohibited. An interpretation of this type would have obvious negative impact on business plans focused on space resources utilisation, and by extension the security of investments in those plans. However, opinion is consolidating around the interpretation that the US law is in compliance with the OST.

A scenario in which multiple nations develop multiple different regulatory philosophies for space resources heightens the political risk faced by the commercial players

Both the International Institute of Space Law (IISL) - the primary international professional society for attorneys in the space sector - and European Union (EU) officials have issued statements indicating belief that the Act is compliant. The Act itself contains an explicit disclaimer of extraterritorial sovereignty.

In February 2016, the Government of Luxembourg announced its intent to develop a specific legal and regulatory regime focused on space resources. While the exact details of this legislation are unknown at this time, it is certain that it will be supportive of the legal right to access, possess, use, transport and sell space resources, as the policy is part of a broader initiative designed to attract space resources companies to operate from Luxembourg.

Regulation and risk

While the question of how the US Act relates to Article II of the OST is not the primary focus of this article, the discussion does highlight the current role of political risk in the nascent space mining industry.

Speaking at a panel in 2013, Bob Richards, CEO of prospective lunar resources company Moon Express, stated there was a risk in assuming governments will be supportive in defending space resources businesses’ rights to operate in space. He said: “We are making some broad assumptions and interpretations to existing treaties that were set up by governments in the past. We are assuming that commercial ventures will be allowed and there will not be some kind of international backlash.”

Signalling this support - ie, reducing political risk and establishing the underlying frameworks to enable activity - is one reason governments enact legislation of the type represented by the US Act. Legislation and regulation is also a means by which governments ensure that they meet obligations to international agreements and treaties. In this regard the US law is as notable for what it does not include, as for what it does.

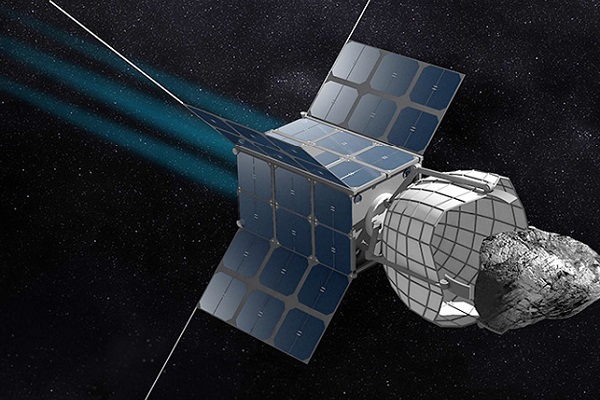

Artist’s concept of DSI’s Dragonfly - its job is to capture an asteroid and retrieve small samples for study and processing

Artist’s concept of DSI’s Dragonfly - its job is to capture an asteroid and retrieve small samples for study and processing

Article VI of the OST establishes an obligation for states to be responsible for the space activities of their entities, including non-governmental actors such as commercial companies. It states, in part, that ‘the activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorisation and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty’. States typically respond to this obligation through national regulations, laws and licensing regimes.

The space resources provisions in the US Act did not establish any elements of this regulatory framework, instead requiring the executive branch of the US government to deliver a

report with recommendations (which would cover other activities in addition to space resources). It can be expected that the pending legislation in Luxembourg might also address a regulatory approach.

This results in a condition of uncertainty – or risk – as the commercial entities continue to execute their business plans. The lack of a regulatory framework does not necessarily create an environment conducive to business development.

The current situation in the US is one in which the government has clearly signalled its intent to support commercial space resources development - but has yet to fully implement the regulatory framework to enable that support. The passage of the US Act, legislative action in other countries and the increasing activities of space resources-focused commercial enterprises creates a window - and a need - for additional action to define a regulatory scheme that reduces the political risk faced by the commercial sector while simultaneously upholding national obligations to the international legal system.

On-orbit authority

The window for further policy and regulatory action is important beyond just the space resources community. The current debate and discussions over the legal and regulatory environment for space resources utilisation can be contextualised into a broader discussion of expanding commercial activities in space.

Many other commercial applications, such as commercial space stations, on-orbit servicing and on-orbit fuel depots may be approaching viability in the coming years. Governments must consider how they will satisfy their supervision and oversight requirements for these new applications. As they do so, the existing regulatory approaches which were originally developed for communications, remote sensing and space launch services will not be sufficient. As commercial activities develop into new areas of application, the regulatory environment must also evolve. The regulatory uncertainty seen in the space resources segment is present elsewhere and, as such, the way in which governments proceed may serve as precedent for how it is addressed in other applications.

In the United States, policymakers have been working to address this issue, under a broad concept known as ‘on-orbit authority’, which would provide for regulatory authority for in-space activities between launch and re-entry that are not covered by existing regimes. The reports required under the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act will contribute to this definitional activity.

International environment

Ultimately, regulatory regimes are developed and implemented at the national level, because space activities are inherently international in execution and the markets being targeted in space resources business plans are global in scope.

Regulation and governmental oversight is part of an overall market framework that provides stability and confidence in validity for commercial entities

While the US and Luxembourg currently have the most visible space resources governance activities, it is unlikely that they will be the only nations to address this topic, and it is unknown whether the approach ultimately adopted in the US will be reflected internationally.

As the IISL states in its December 2015 ‘Position Paper on Space Resource Mining’, the new US Act is ‘a possible interpretation of the Outer Space Treaty. Whether and to what extent this interpretation is shared by other States remains to be seen’.

Although different interpretations of the treaty could exist simultaneously, such a situation could complicate the merchantability and marketing of space-derived resources or products fabricated from them.

The potential for a scenario in which multiple nations develop different regulatory philosophies for space resources heightens the political risk faced by the commercial players. It also increases the risk for political friction between nations over the potential economic benefits of space resources.

One of Planetary Resources’ targets is an X-type asteroid which may contain more platinum than has ever been mined on Earth to date. Composed of primarily metal, they are known for being extremely dense, unlike any metallic ore bodies we find on Earth today

One of Planetary Resources’ targets is an X-type asteroid which may contain more platinum than has ever been mined on Earth to date. Composed of primarily metal, they are known for being extremely dense, unlike any metallic ore bodies we find on Earth today

To mitigate this concern, a group of government, academic, civil society and commercial entities (including many of the space resource focused companies) have joined to form The Hague Space Resources Governance Working Group, of which the author’s organisation - Secure World Foundation - is a founding partner.

Over a two-year period, which began in the autumn of 2015, the Working Group aims to build consensus on the elements of a regulatory framework for space resources activities. That framework will then be presented to the international community for consideration in both international and national regimes.

An international consultative process, such as that represented by the Working Group, is the best path forward to ensuring that the development of space resources activities occurs in a way that reduces uncertainty faced by commercial actors and builds confidence in the international community that activity will be fully compliant with international obligations.