With space forecast to be a US$1.8 trillion market by 2035, the claim that it’s “everyone’s business” at the 2nd annual Space Economy Summit in December 2024 was not far wide of the mark. The Summit, organised by The Economist magazine group and sponsored by the Portuguese Space Agency, brought together 500 space industry attendees from all corners of the globe to hear and interact with a high-profile list of speakers at the Nova School of Business and Economics in Carcavelos, Portugal. Clive Simpson, ROOM Editor-in-Chief, reports on two of the keynote speakers, neither of whom shied away from throwing out a challenge on opposite sides of the spectrum, not only to those present but to the global space community at large.

In a passionate keynote speech, astrophysicist and space environmentalist Moriba Jah centred on the idea that humans have shifted from acting as stewards of the planet to pursuing ownership, a worldview that he argues is accelerating environmental harm in domains ranging from land and ocean to outer space.

Drawing parallels with how colonialism disrupted indigenous cultures in Hawaii, his birthplace, he suggested that as a general principle “stewardship” was preferable to “ownership” because it leads to more “responsible” actions.

Keynote speaker Moriba Jah, co-founder and chief scientist of GaiaVerse Ltd.

Keynote speaker Moriba Jah, co-founder and chief scientist of GaiaVerse Ltd.

Reflecting on the increasing severity of climate and environmental crises, Jah emphasised that “year after year we witness Mother Earth displaying signs of ecological stress” – from rising temperatures to flooding and other extreme events” – a stark warning that everything is interconnected. “Land, air, ocean and space are not disjointed mutually exclusive domains, it’s all very holistic,” he said.

“Year after year we witness Mother Earth displaying signs of ecological stress”

Jah suggested that humanity had largely abandoned its “intergenerational contract” in lieu of “ownership” and warned that such abandonment is also unfolding in space, where “every single domain of human exploration has been led by those most resourced and has resulted in the detriment of the environment, and space is no different.”

Jah recounted his professional experiences at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the European Space Agency and the US Air Force Research Laboratory on Maui, where he found himself astonished by the vast number of non-functioning objects orbiting Earth. “In 2006, out of 26,000 objects, 1200 were working and everything else was garbage.” By 2024, that catalogue had doubled. “We are now tracking 50,000 objects and space will not ever, ever be what it was in 1956 – it will never be clean,” he stated.

He likened discarded satellites and spent rocket bodies to “single-use plastics” in orbit. “Everything that we launch in space is a single use plastic equivalent,” he lamented. Despite the convenience and technological benefits of sending satellites into lower orbits, Jah underscored the questionable practice of simply waiting for atmospheric drag. “Leave, abandon, wait for Mother Nature to take care of it. That is the name of the game in space,” he said.

For Jah, part of the solution lies in transitioning from a linear space economy to a circular economy - in other words, designing spacecraft from the outset for reuse or recycling. “Re-usable rockets are possible - that’s got to be the way. Re-use and recycle is the name of the game and we need governments to incentivise circularity.”

He drew attention to historical environmental responses, such as global efforts to curb chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) to protect the ozone layer, and the sudden return of wildlife during COVID-19 lockdowns as evidence of nature’s resilience. “When humans take the foot off the gas pedal of stupidity, Mother Nature shows that she is capable of achieving equilibrium,” he stated.

Jah urged the audience not to underestimate their individual and collective power to drive responsible change. “I’m telling you this, because people here feel that they’re powerless… let’s start demanding stuff, reclaim your sovereignty, recognise that you have choices.” But he warned that “if we lose space, we can’t achieve Earth sustainability,” since satellites provide critical observations for managing life on Earth.

Moreover, Jah decried the rush to populate orbit “just because we can”. Reflecting on how the public often waits for a large-scale disaster before acting, he said: “People keep on telling me - we’re not going to change anything until something bad happens… has something bad not happened already?”

Panel discussion chaired bv Alok Jha (left), science and technology editor, The Economist.

Panel discussion chaired bv Alok Jha (left), science and technology editor, The Economist.

Moriba Jah’s keynote challenged the space community to abandon the mindset of ownership in favour of stewardship, invoking parallels between polluted oceans and an increasingly crowded and debris-strewn orbit. His advocacy for a circular space economy highlights the urgent need to rethink how we design, launch and dispose of satellites.

By taking responsible measures now, adopting reusability and insisting on improved regulatory frameworks, the space sector has an opportunity to safeguard orbital highways for current and future generations, according to Jah.

“People keep on telling me - we’re not going to change anything until something bad happens… has something bad not happened already?”

“In doing so, we not only protect vital satellite infrastructure essential for life on Earth - but also uphold our intergenerational contract to care for the planet, from the ground beneath our feet all the way to space.”

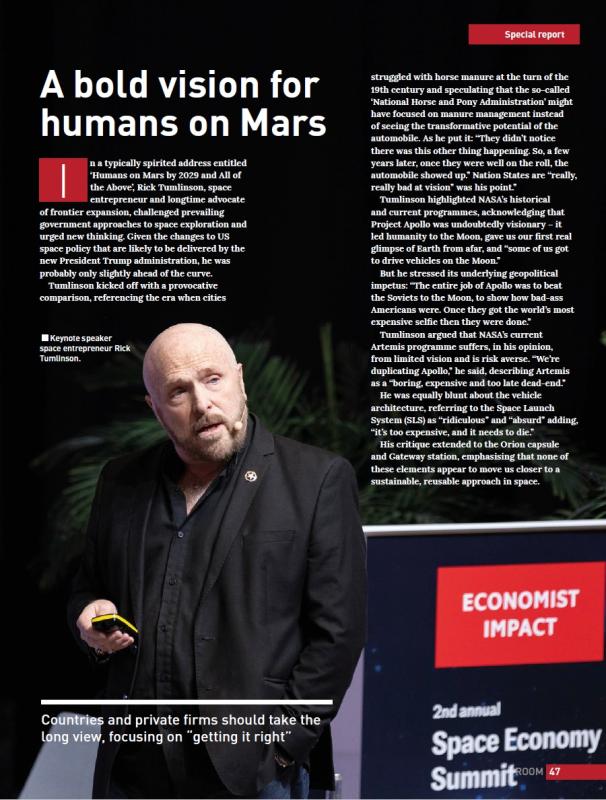

A theme of Tumlinson’s address was the importance of reusability. He firmly believes the future belongs to “rocket ships” rather than single-use rocket stages and capsules: “You notice I’m using the words rocket ships… we can use them over and over again.” He observed that large-scale reuse is already happening in the private sector - both from new entrants and established names - and he suggested this trend heralds a new era of space access. For Tumlinson, this is reminiscent of the advent of the railroad, the steamship and the aircraft. “We are about to open the railroad to space,” he asserted.

Central to Tumlinson’s message is the idea of landing humans on Mars by 2029. He suggested that persuading leadership - particularly in the United States - to commit to a near-term Red Planet goal could inspire the next generation and continue to expand private-sector innovations in space.

Among the dozens of speaker participants were Anousheh Ansari (pictured), chief executive, XPRIZE; Dylan Taylor, chairman and chief executive, Voyager Space; Ricardo Conde, President, Portuguese Space Agency; and Lindy Elkins-Tanton, principal investigator of NASA’s Psyche mission.

Among the dozens of speaker participants were Anousheh Ansari (pictured), chief executive, XPRIZE; Dylan Taylor, chairman and chief executive, Voyager Space; Ricardo Conde, President, Portuguese Space Agency; and Lindy Elkins-Tanton, principal investigator of NASA’s Psyche mission.

He quipped about the persuasive tactics an influential entrepreneur might use: “What would I do if I was that guy? Elon M… I would say, let’s go to Mars. Let’s pick Mars if we can. Why not? You can be like John Kennedy, you can be famous.”

While Tumlinson admitted that he once opposed quick-return “flags and footprints” missions, he sees a new scenario emerging - one driven by passion, private funding and a repeated cycle of trips that ultimately leads to permanent settlement.

Practical challenges remain, but Tumlinson suggested these are “way simplified” compared to the complexity of the Artemis architecture, especially if “we leverage fuel depots and repeated in-space refuelling”.

Tumlinson urged governments to stop “down-selecting” too early on potential solutions, comparing NASA’s approach to awarding single or limited contracts as reminiscent of an older era in which “they’re still existing in this old way of doing things.”

Instead, he advocated a broader approach, saying: “There’s a lot of great ideas, they all have very different approaches and each one of them seems to have at least one or two major breakthrough ideas.”

He suggested enabling “the orbital street to grow” by using policy tools - like zoning, taxes, or tenancy incentives - akin to how a mayor would revitalise a city.

As for the Moon, Tumlinson argued that countries and private firms should take the long view, focusing on “getting it right”. He strongly supports international and commercial cooperation on the lunar surface, advocating the concept of a global base where “we can keep an eye on them”, turning former international competitors into collaborators.

Yet he proposes the ‘Lunar Bella Protocol’ which would forbid large-scale industrialisation on the Earth-facing side “I do not want to condemn all of future generation to having to look up and see the Man on the Moon cut up by a strip mine. Let’s at least show a little class as we go this way.” He pointed out that “most of the good stuff is in the poles on the far side”, so balancing aesthetics, cultural heritage and resource exploitation could be feasible.

Many of the great achievements of all time were not driven by the bottom line

Beyond the Moon and Mars, Tumlinson championed the idea of free space habitats - huge, rotating structures in which humans could maintain full Earth gravity. He invoked Gerard K O’Neill’s vision and alluded to Jeff Bezos’s fascination with it, describing a future of giant orbital cities. The true hurdle, in his view, is not technology but psychology - being willing to imagine “why we are here”.

Ethan Barajas, co-founder and CEO of startup Icarus Robotics, questions one of the speakers.

Ethan Barajas, co-founder and CEO of startup Icarus Robotics, questions one of the speakers.

For Tumlinson, the driving force in humanity’s push outward is summed up in three words - heart, vision and dreams. While paying for spaceflight and enabling commerce matters, it is not the sole cause for exploration because many of the great achievements of all time were not driven by the bottom line. He argued that we need both the dreamers and the doers if we are to “open up the universe”.

Rick Tumlinson’s keynote underscored a yearning for boldness and inclusivity in space exploration. He insists that governments must relinquish old approaches, embrace the swift innovation of the private sector and focus on building a sustainable, forward-looking framework for Moon and Mars missions. Above all, he reminds us of the power of vision and the uniquely human drive to push beyond horizons - a drive that, if harnessed correctly, could usher in a new age of cosmic exploration and settlement.

Kathryn Lueders, general manager, Starbase, SpaceX, being interviewed by Oliver Morton, briefings editor, The Economist.

Kathryn Lueders, general manager, Starbase, SpaceX, being interviewed by Oliver Morton, briefings editor, The Economist.

Editor’s note

The 2nd annual Space Economy Summit in December 2024, organised by The Economist magazine group and sponsored by the Portuguese Space Agency, was held at the Nova School of Business and Economics in Carcavelos, Portugal

Photos courtesy of Space Economy Summit photographers.