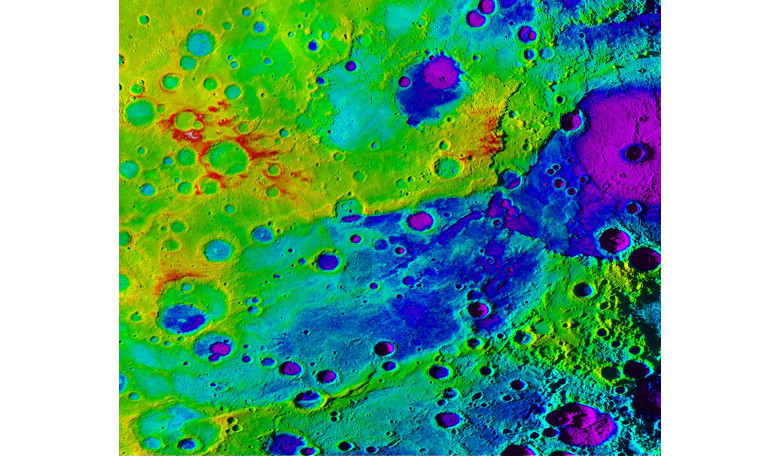

An international team of astronomers have found a giant valley on Mercury that if it existed on Earth would be almost twice as deep as the Grand Canyon and would reach from Washington, D.C. to New York City, and as far west as Detroit.

The ‘great valley’ which lies in the planet's southern hemisphere and overlaps the Rembrandt Basin – a large crater formed by a relatively recent impact – was found using stereo images from NASA's MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft.

Its discovery reveals important clues as to the geologic history of the innermost planet in our solar system as the sheer vastness of the valley indicates processes at work that have not occurred on our own planet during its early history.

Earth has a crust and upper mantle which together are known as the lithosphere. The lithosphere is divided into multiple tectonic plates, and it is at these boundaries where earthquakes and volcanic eruptions arise as the plates push against each other, or ride under or over each other. However, Mercury has a single, solid lithosphere that covers the entire planet, therefore it is suggested that as the planet cooled and shrank roughly 3-4 billion years ago, the planet’s lithosphere buckled and folded to form the valley.

"This is a huge valley. There is no evidence of any geological formation on Earth that matches this scale," said Laurent Montesi, an assistant professor of geology at UMD and a co-author of the research paper. "Mercury experienced a very different type of deformation than anything we have seen on Earth. This is the first evidence of large-scale buckling of a planet." This buckling has been likened to the skin of a grape as it dries to become a raisin leaving deep folds in its once smooth surface.

Exactly how the valley formed is as tantalising as the sheer size of it according to Montesi and his co-authors. From the images, the team have ascertained that the valley's walls appear to be two large, parallel fault scarps that plunge steeply to the flat valley floor below. The fault scarps are step-like structures where one side of a fault has moved vertically with respect to the other. Consequently, the team suggest that the best explanation to explain the formation is that the entire floor of the newly discovered valley is one giant piece of Mercury's thick lithosphere that has dropped between the two faults.

Nonetheless, this explanation only works if it is assumed that like most planets, Mercury has been steadily cooling since its formation. However, evidence for recent volcanism and an active magnetic field imply that the planet is still warm inside. "Everyone thought Mercury was a very cold planet – myself included. But it looks like Mercury might have heated significantly in recent planetary history,” said Montesi. If true, this analysis would overturn some time-tested assumptions about Mercury's geologic past.