This week the Massachusetts Institute of technology (MIT) hosted the first TESS Science conference dedicated to the multitude of discoveries NASA’s planet hunting telescope has helped uncover in its first year of operation.

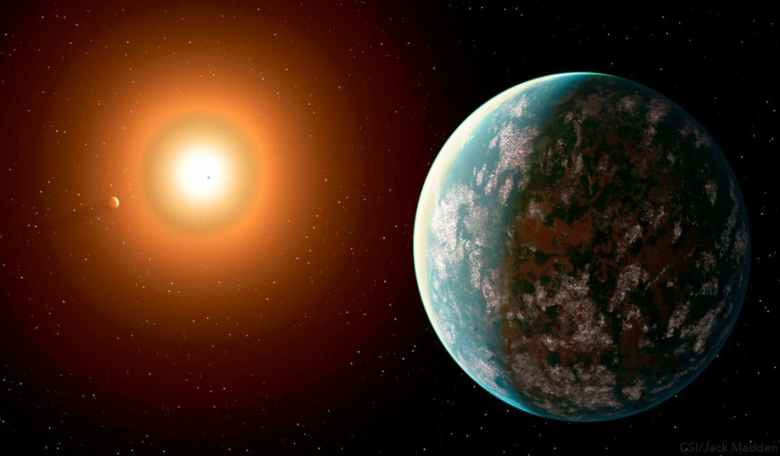

One of the most intriguing discoveries just announced is GJ 357 d; a super-Earth located about 31 light-years away orbiting a diminutive M-type dwarf star that has been described as relatively inactive.

So far nearly 200 exoplanets have been discovered orbiting similar type stars in the solar neighbourhood. However out of all of these, bulk properties such as density, mass and radius are only known for 11 M dwarf planet systems.

Why is this important? Scientists need to know a planet’s mass and radius in order to calculate its mean density. With this information then can then derive its composition and work out how amenable it is to hosting life.

Interestingly, GJ 357 d is not alone. Two other planets also circle around the same host star; a so-called “hot Earth” that is about 22 percent larger than our planet. Known as GJ 357 b, this scorching world orbits 11 times closer to its star than Mercury does our Sun. Without accounting for the additional warming effects of a possible atmosphere, this gives this piping hot exoplanet an equilibrium temperature of around (254 degrees Celsius (490 degrees Fahrenheit).

Its companion, GJ 357 c, which although more Earth-sized – it has at least 3.4 times Earth’s mass – is also a sizzler. This hot-body is as hot as 126 degrees Celsius (260 degrees Fahrenheit) and it orbits the star every 9.1 days.

Of this trio of planets, both the mass and radius is only known for GJ 357 b and the international team of scientists led by Rafael Luque, at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands (IAC) on Tenerife who discovered the system, have calculated that it has a mean density like Earth. However GJ 357 b is far too fiery and unbearable hot for life as we know it to exist.

What makes its smaller neighbour GJ 357 d so interesting is that it is located within the outer edge of its star’s habitable zone, where, as it whizzes around around its host star in 56 days, it receives about the same amount of stellar energy from the dwarf star as Mars does from the Sun. This places the exoplanet right in the sweet spot for life to occur.

Although its density is not known, yet, chances are it could be a rocky world like its neighbour and, if it turns out GJ 357 d has a dense atmosphere for example, which future studies could help determine, “it could trap enough heat to warm the planet and allow liquid water on its surface,” said co-author Diana Kossakowski at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany.

Wasting no time in determining just what type of conditions GJ 357 d might succumb too, in an additional paper completed by Lisa Kaltenegger, associate professor of astronomy, director of Cornell’s Carl Sagan Institute and a member of the TESS science team, along with doctoral candidate Jack Madden and undergraduate student Zifan Lin, the team simulated three different types of atmosphere for GJ 357 d to see which could sustain surface habitability.

The team found that if GJ 357 d has a geological cycle that regulates carbon dioxide concentration like on Earth, then the surface would be lovely and warm and possibly quite liveable. However if it doesn’t then the news is not so favourable and GJ 357 d is likely to be a frozen rocky body that is not so hospitable for heat-loving humans.

To find out for sure, GJ 357 d needs to pass in front of its host star so that researchers can use the transit information to work out its density - like they did for its larger, hotter accomplice GJ 357 b.

If this happens, GJ 357 d would become the closest transiting, potentially habitable planet in the solar neighborhood. Even if GJ 357 d does not transit, Kaltenegger and colleagues go on to say in their paper “the brightness of its star makes this planet in the Habitable Zone of a close-by M star a prime target for observations with Extremely Large telescopes as well as future space missions.”

“This is exciting,” says Kaltenegger who helped discover GJ 357 d, “as this is TESS’s first discovery of a nearby super-Earth that could harbour life.”