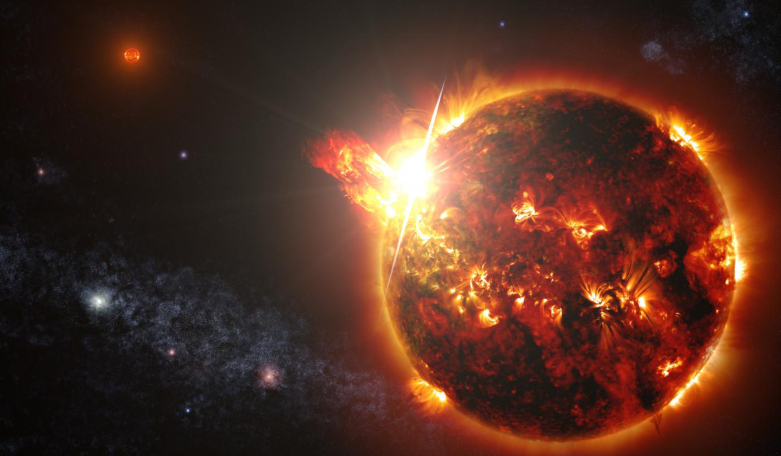

When researchers discovered an exoplanet around our nearest star four years ago, it seemed the perfect object in which to mount an exploration mission in the hopes of finding life. But then further studies showed that Proxima b was subjected to regular outbursts of radiation from its nearby star in the form of stellar flares, dashing hopes that the planet might be habitable.

But now a new study by scientists at Northwestern University say that actually, stellar flares are not such a bad thing and that they could play an important role in the long-term evolution of a planet's atmosphere and habitability.

With a vast human population dependant on satellites for everyday life, stellar flares from an Earth perspective are not that great.

They may look pretty when viewed from far away, but the very high-energy particles spewed out by the Sun have the potential to affect power grids, bathe high-flying airplanes with radiation, disrupt satellites and even cause them to fail.

Solar storms in space are also dangerous. If large enough doses of radiation are received by an unshielded astronaut, it can have fatal consequences for the unlucky recipient.

The situation doesn’t get better elsewhere in the universe, as robust stellar flares have the ability to deplete and destroy atmospheric gases, such as ozone (O3).

Ozone is a key molecule on Earth as it helps block harmful levels of ultraviolet (UV) radiation from reaching the ground. If allowed to penetrate through our planet's atmosphere unheeded, it could have a damaging impact on surface life.

But despite the damage these unpredictable and often violent stellar flares can inflict, it might not all be doom and gloom.

After an extensive study of planets orbiting within the habitable zones of M and K dwarf stars – the most common stars in the universe – a team of researchers used a combination of 3D atmospheric chemistry and climate modelling to see what effects the flares have on an exoplanet’s habitability.

"Habitable zones around these stars are narrower because the stars are smaller and less powerful than stars like our sun. On the flip side, M and K dwarf stars are thought to have more frequent flaring activity than our sun, and their tidally locked planets are unlikely to have magnetic fields helping deflect their stellar winds,” says Daniel Horton, an assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences in Northwestern's Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and the study's senior author.

Their study was no easy task as flares can last for hours or days and as such these brief timescales can be difficult to simulate.

In order to form a more complete picture of exoplanet atmospheres, the researchers incorporated flare data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Satellite Survey, launched in 2018, into their model simulations.

The team, made up of scientists at Northwestern, University of Colorado at Boulder, University of Chicago, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and NASA Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS), found that surprisingly, stellar flares emitted by a planet's host star do not necessarily prevent life from forming.

"We compared the atmospheric chemistry of planets experiencing frequent flares with planets experiencing no flares. The long-term atmospheric chemistry is very different," said Northwestern's Howard Chen, the study's first author. "Continuous flares actually drive a planet's atmospheric composition into a new chemical equilibrium."

"We've found that stellar flares might not preclude the existence of life," added Horton. "In some cases, flaring doesn't erode all of the atmospheric ozone. Surface life might still have a fighting chance."

Whats more, stellar flares might make it easier to detect life if it has managed to get established. This is because stellar flares can increase the abundance of life-indicating gasses such as nitrogen dioxide, nitrous oxide and nitric acid, from barely there to detectable levels.

"Space weather events are typically viewed as a detriment to habitability," Chen said. "But our study quantitatively shows that some space weather can actually help us detect signatures of important gases that might signify biological processes."

The team’s study, the “persistence of flare-driven atmospheric chemistry rocky habitable zone worlds," was published this week in the journal Nature Astronomy.