In our search for a planetary home away from home, the hunt for Earth mark II might prove more difficult than imagined as a new analysis of known exoplanets has revealed that Earth-like conditions on potentially habitable planets may be much rarer than previously thought.

We need only look at our neighbours, Mars and Venus, to see that if conditions are not right, then the essential ingredients to make a planet habitable for life as we know, such as liquid water and a decent non-toxic atmosphere, are long lost, rendering the surface unliveable. For humans at least.

We need only look at our neighbours, Mars and Venus, to see that if conditions are not right, such as a lack of liquid water or a toxic or thin atmosphere, then the chances of intelligent life getting established are pretty slim.

And, as far as we know it, a planet also needs to be placed in a sweet spot known as the habitable zone - the region around a star where the temperature is just right for liquid water to exist on the surface – to boost its chances of harbouring life.

It’s a lot to ask for, perhaps too much, as after taking all of these caveats into consideration, it turns out that from the thousands of known exoplanets in the Milky Way, only a handful of such rocky and potentially habitable exoplanets are known.

Even then, none of these worlds has the theoretical conditions to sustain an Earth-like biosphere by means of ‘oxygenic’ photosynthesis - the process plants on our planet use to convert light and carbon dioxide into oxygen and nutrients.

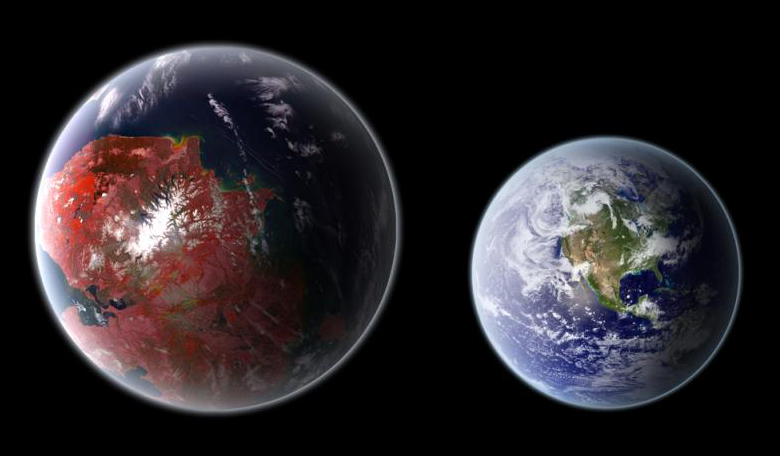

All except one. That planet is Kepler-442b; a rocky planet about twice the mass of the Earth, orbiting a moderately hot star to receive just about enough stellar radiation necessary to sustain a large biosphere.

Making the dire prediction that habitable planets are few and far between is a team of Italian astronomers who looked in detail at how much energy is received by a planet from its host star.

The energy they were specifically looking at comes from a region in the electromagnetic spectrum that corresponds more or less with the range of light visible to the human eye; a spectral range known as photosynthetically active radiation (PAR).

By studying the amount of PAR a planet receives from its host star, the team where able to measure whether living organisms would be able to efficiently produce nutrients and molecular oxygen via normal i.e Earth-like oxygenic photosynthesis.

The results were not great. The data showed that stars with temperatures about half that of our Sun, which sizzles at 5,778 K, cannot sustain Earth-like biospheres because they do not provide enough energy in the PAR wavelength range of 400 to 700 nanometres.

Oxygenic photosynthesis would still be possible, but such planets could not sustain a rich biosphere say the team.

Red dwarfs, the most common type of star in the galaxy, that has temperatures roughly a third of our Sun’s, did not fair much better either. Although these smaller stars can shine for more than a trillion years, the study showed that they could not receive enough energy to even activate photosynthesis.

This could be a blow for those hoping to find signs of life around TRAPPIST-1, a system with 7 Earth-sized planets, three of which reside in its habitable zone, that lies around 40 light years away.

“Since red dwarfs are by far the most common type of star in our galaxy, this result indicates that Earth-like conditions on other planets may be much less common than we might hope,” Giovanni Covone of the University of Naples, lead author of the study says.

When the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) launches later this year, it will have the sensitivity to study the atmospheres of exoplanets and to search for the building blocks of life elsewhere in the Universe.

However, with such stringent conditions on stellar and planet properties needed for complex life to evolve, are hopes already dashed before JWST gets off the ground?

“Unfortunately it appears that the “sweet spot” for hosting a rich Earth-like biosphere is not so wide,” Covone says.

This research has been published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.