Scientists using a neural network to search through the enormous Kepler dataset have found an eighth planet in a distant exoplanet solar system known as Kepler 90. This is the first system other than our own that has been found to harbour eight planets orbiting its host star.

Kepler 90 is G0 type star, meaning it is a little bit hotter and a little bit more massive than our Sun and is located 2, 545 light years away. The newly discovered planet – Kepler-90i – is a small, rocky world about 30 percent larger than Earth, and it whizzes round its host star once every 14.4 days.

All of the planets in the Kepler-90 system are closer to their central star than the Earth is to the Sun. Because Kepler-90i orbits so close to its host star, its average surface temperature is believed to exceed that of Mercury's – around 427 degrees celsius (~800 degrees fahrenheit). With a surface temperature that is hot enough to melt lead, it is unlikely that life as we know it could exist there.

Speaking at a media conference today, Andrew Vanderburg, a NASA Sagan Postdoctoral Fellow and one of the two scientists who discovered the planet, said; “This is the first system that we know of that has a family of eight planets orbiting its host star just like our own.”

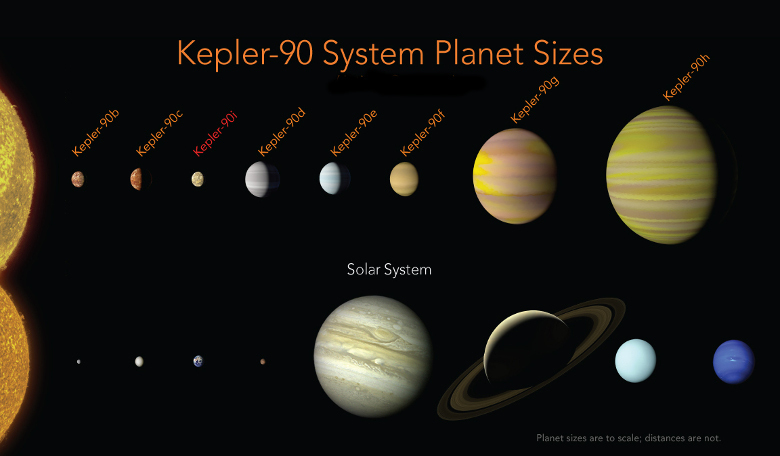

“The Kepler-90 star system is like a mini version of our Solar System. You have small planets inside and big planets outside, but everything is scrunched in much closer,” explained Vanderburg.

Kepler’s four-year dataset consists of 35,000 possible planetary signals, and even if someone had managed to sift their way through all of those images, it is possible that the planet could have been overlooked anyway due to the weak signal it produced in the data.

The space telescope is set up to detect the miniscule change in brightness captured when a planet passes in front of its host star, but small, rocky worlds such as Earth are notoriously difficult to detect at the best of times.

Instead, Vanderberg, along with his colleague Christopher Shallue, a senior software engineer with Google’s research team Google AI, trained a neural network to do the work a human couldn’t. By scanning 15, 0000 previously-vetted signals from the Kepler exoplanet catalogue, the network ‘learned’ to detect what an actual transiting exoplanet signal looked like.

Once completed, the researchers set the network to the task of searching for weaker signals in 670 star systems that already had multiple known planets - a good place to start when looking for more smaller companions.

In the test dataset, the neural network correctly identified true planets and false positives 96 percent of the time. “Machine learning really shines in situations where there is so much data that humans can't search it for themselves,” said Shallue.

“We got lots of false positives of planets, but also potentially more real planets,” continued Vanderburg. “It’s like sifting through rocks to find jewels. If you have a finer sieve then you will catch more rocks but you might catch more jewels, as well.”

To show that Kepler-90i was not a one off find, the team also identified a sixth planet in the Kepler-80 system. Now known as Kepler-80-g, this newly found Earth-sized world is locked in an extremely stable system with four of its neighbouring planets by their mutual gravity – a system that is reminiscent of TRAPPIST-1 set of planets.

“These results demonstrate the enduring value of Kepler’s mission,” said Jessie Dotson, Kepler’s project scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. “New ways of looking at the data – such as this early-stage research to apply machine learning algorithms – promises to continue to yield significant advances in our understanding of planetary systems around other stars. I’m sure there are more firsts in the data waiting for people to find them.”

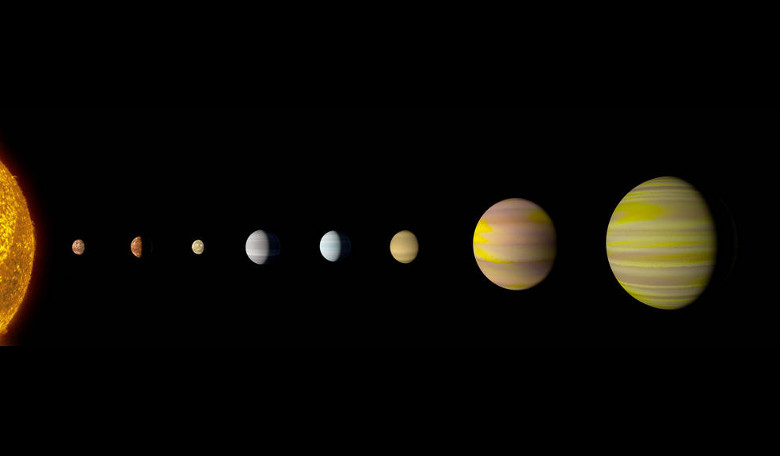

The Kepler-90 planets have a similar configuration to our solar system with small planets found orbiting close to their star, and the larger planets found farther away. However all of these planets orbit closer to their central star than the Earth is to the Sun (planet sizes are to scale, distances are not). In our solar system, this pattern is often seen as evidence that the outer planets formed in a cooler part of the solar system, where water ice can stay solid and clump together to make bigger and bigger planets. The pattern seen around Kepler-90 could be evidence of that same process happening in this system. Image: NASA/Ames Research Center/Wendy Stenzel