Overcoming challenges of all kinds is a mainstay of global space exploration and commercial space development, but how do those in the business feel about challenging the very essence of humanity’s future in space - or at least the pathway to get there? In her new book, Ground Control, anthropologist Savannah Mandel experiences an everyday ‘moment of rupture’ which sets off deep reflections about the journey ahead. Her article for ROOM, an edited extract from Ground Control, raises a series of tough questions for the commercial space industry and humanity at large.

I continued to stare, causing the line of disgruntled passengers being shepherded out of the station to come to a shuddering halt. Someone pushed me, bumping my shoulder as they shoved past. I exhaled. How long had I been holding my breath?

It was as if roots had sprouted from my feet and grown straight down through my boots. As if Mother Earth herself had turned my head and said, “Look. Look, you fool. They will be left behind. What say have they had in these conversations about space, child? You’re dreaming of the stars while this is happening?”

It was March 2018 and protesters were calling for an end to the Turkish invasion of Syria and the mass murder of Kurdish people. We, London commuters, weren’t forced to stay in King’s Cross Station, and let’s be honest, that would have made bigger news than the protest itself. Instead, transport officials kept the rear entrance farthest from the protestors open.

Watching demonstrators protesting against Turkey’s military offensive on the Kurdish-controlled town of Afrin in Syria at London’s Kings Cross station in November 2018 was the start of Savannah Mandel’s ‘moment of rupture’ that caused her to challenge the largely accepted norm of human exploration.

Watching demonstrators protesting against Turkey’s military offensive on the Kurdish-controlled town of Afrin in Syria at London’s Kings Cross station in November 2018 was the start of Savannah Mandel’s ‘moment of rupture’ that caused her to challenge the largely accepted norm of human exploration.

But rather than leave and escape the conflict, I walked up to the second floor of the station, sat down and stared out the window at the individuals packed together, holding signs, marching the streets of London. It had started to rain. My field notes hung limp in my hands.

Who was really benefitting from human space exploration? How many other protests were happening around the world at that moment? What problems were facing Earth then, at the very moment I was daydreaming about creating colonies on Mars and sending tourists into low Earth orbit? And why was I, an anthropologist, researching outer space? Weren’t we supposed to dig up artifacts and study villagers in a rainforest? Or maybe solve murder mysteries with forensics? Why was I helping any space capitalists hide skeletons in their closets?

Alternative future

My story starts at a moment of rupture, a night when the curtain was ripped down and an alternative future behind the veil was exposed. I’m speaking in metaphors, of course, as those who write about human space exploration often do, but let me pause before continuing and make myself very clear: there are no utopian visions or interstellar daydreams or biographies of ‘rockstar’ billionaires in this story about space. This is a story that is as raw as it is grounded. It doesn’t leave out the awkward small talk or the inappropriate jokes made over happy hour cocktails. These words are messy. They are human.

I was challenged to consider who really benefits from human space exploration if access is granted only to those who have the money to get there in the first place

In my book I trace the commercial space race (as many have before), but rather than focus on its rise, I describe what might arguably be its downfall. I make an argument for an alternative future. One which includes the voices seldom invited into techno-scientific conversations.

I investigate the construction of global priorities and beliefs as ‘global’ becomes increasingly local. I do so through a realm of expertise as new as the commercial space race: outer space anthropology. And it is through this lens of expertise that I confront current and historic perceptions of human space exploration.

Who really benefits from human space exploration when access is granted only to those who have the money to get there in the first place? Should humans explore space at all? Is it worth it to send humans to space? What cultural outcomes will result from continued human space exploration and the colonisation of other worlds? And lastly, what can we learn about our present selves by studying our most extreme visions of the future?

My confrontation began at King’s Cross in 2018 and caused me to travel back in time to examine moments in our history and the present that act as analogues for our future.

To understand what motivates our species’ drive to explore - and our most imperialist urges - I’ve examined colonial histories and inequitable social structures stretching from ancient Greek history to the present day. I’ve resurrected often unacknowledged Apollo-era protests and dissent, which are reflective of space ethics and protests that circulate in social media today. I have, from there, revisited historic moments, such as the invention of Concorde and the exploration of Antarctica, as a way of understanding technological ventures such as Virgin Hyperloop and Virgin Galactic.

I have also endeavoured to shine a spotlight on congressional discourse, annual budgets, fictional representations, the narratives promoted by leading commercial space companies, space law and social media, to tease apart answers to the questions posed above.

Sometimes this story is full of love and hope. Sometimes it’s full of anger and resentment. This is how I was trained to write as an anthropologist: not to avoid bias but to be up front with it, to acknowledge emotion and reflexivity as part of the story. This is why I start with a moment of personal transformation.

Was my railway station protest revelation the moment I transitioned from a firm believer in and advocate for the space industry, to someone who couldn’t shake a guilty feeling that shadowed the prospect of human space exploration?

Not exactly. Like most personal transformations, this coming of age is akin to a botanical creeping. Vine-like tendrils pried away celestial concrete one brick at a time. An Earthly growth, sometimes painful, sometimes breathtaking. But make no mistake - I want to go to outer space. I want to see humankind construct cities on far-off planets and moons. That doesn’t make it right though, and it doesn’t mean that now is the time to do it.

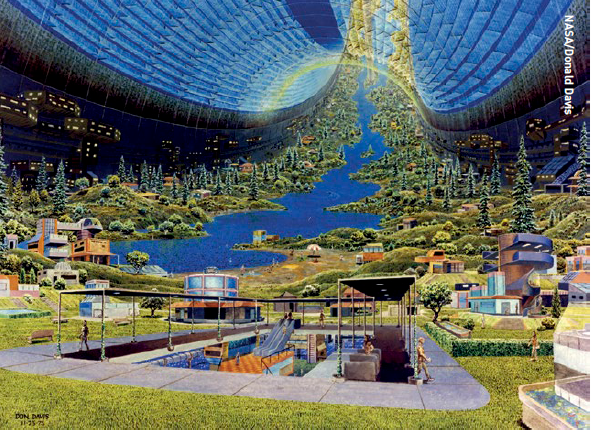

The ‘Stanford Torus’, a space station design from the 1975 NASA Ames/Stanford University Summer Study by Donald Davis. In his painting, the artist wanted to emphasise the challenge of sustaining a closed ecosystem in space. The urge to explore outer space, to discover, to colonise and ensure humanity’s future, goes back much further than we might think. Human space travel first appeared in literature many centuries before it became a possibility in the ‘real world’.

The ‘Stanford Torus’, a space station design from the 1975 NASA Ames/Stanford University Summer Study by Donald Davis. In his painting, the artist wanted to emphasise the challenge of sustaining a closed ecosystem in space. The urge to explore outer space, to discover, to colonise and ensure humanity’s future, goes back much further than we might think. Human space travel first appeared in literature many centuries before it became a possibility in the ‘real world’.

Utopian demands

The startling idea that human space exploration might not be the best decision for mankind destroys the part of me that yearns for voyages into the unknown

Humankind is faced with two very different utopian demands. The first is the demand to explore outer space. To colonise. To ensure humanity’s future. To search. To learn. To acquire new resources and conduct research.

The second is the demand to stay on Earth, to conserve, to repair, to care, to maintain and to sustain. This alternative vision of the future flows from the mouths of caretakers and conservationists - individuals who seek out restoration of the planet our species was designed for.

The ‘Caretaker’s Demand’ argues that the money spent on advancing human space exploration might be better spent focusing attention back on planet Earth: on realising post-scarcity futures, socialised healthcare, a world without territorial claims-making or colonialism and other Earth-focused demands.

I can’t deny that coming to terms with the prospect of not exploring outer space is hard. The startling idea that human space exploration might not be the best decision for mankind destroys the part of me that yearns for voyages into the unknown. A restlessness creeps in, not unlike a restlessness I felt through the Covid-19 quarantine.

As someone who has researched the space industry for several years now, who has engaged deeply with speculative ideals, the prophetic and the imaginary, and as someone who intensely loves the legacy of science fiction, I struggle with letting go of some of these more transcendental dreams.

I also recognise the social fallout that can occur when making such a decision. If I side with utopian demand number two - the Caretaker’s Demand that asks us not to explore the unknown but to focus attention on socioeconomic problems here on Earth - there go my prospects of working in the space industry, there goes my LinkedIn network.

If my anthropological fieldwork taught me anything, it was that arguing against human space exploration would alienate me from the space industry. But we have to make tough decisions as adults, don’t we?

We have to choose to tell the stories that go untold, to share the memories that might get us blacklisted, to stand up for the perspectives shadowed by the legacies of billionaires, to address racism, sexism, ableism and colonialism. And the decision to leave Earth is one our entire planet is facing as we get closer and closer to the goals shared by so many commercial space companies. But it is a decision that very few get a say in.

Expansive dreams

What would it do to humankind’s collective psyche if we let go of the dreams of expanding human civilization into space?

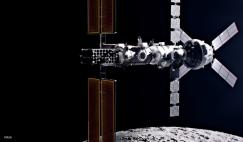

In November 1998, the first module of the International Space Station (ISS) was launched into space. A decade prior to that, the Russian Mir space station was already maintaining a human population in space - beginning in March 1986 until it was decommissioned in June 2000. Which means that for the entirety of my life human beings have been up there, looking down on us.

What if we stopped seeking out poisonous atmospheres and bad relationships with foreign bodies, and focused on the wreckage in front of us?

My mother used to wake us up to go trace the ISS with our fingers as it passed above our home, and I used to think, “There they are… astronauts. Always watching. Always there. Always above us.”

Now there’s talk of the ISS’ imminent demise - due to its age, maintenance requirements and expensive upkeep - and its replacement with a commercial space station. Though the prospect of the ISS’ end shakes me, I’m left wondering what would happen if we didn’t replace it. What if, like any other bad, crumbling, expensive relationship… we let it go? And instead of jumping into another bad, crumbling, expensive relationship, what if Mother Earth and her beautiful inhabitants just stayed single for a while and focused on themselves?

What if we stopped seeking out poisonous atmospheres and bad relationships with foreign bodies, and focused on the wreckage in front of us? That absolutely decimated, overpopulated, polluted planet we were born into.

What if we focused, not on the spacefaring generation, but every generation? What if Earth became our trillion-dollar project? What if, instead of looking up and always begging for more, more, more, we stopped, accepted what we were given, and spent all that pent-up passion and wonder and curiosity on harnessing the deepest, hottest hydrothermal vents, the blistering desert sun, windswept northern oceans and frozen tundra?

What if we found new ways of existing in the harsh places we’ve ruled out on our home world before forcing ourselves into the ecosystems of others? The depths of the oceans, the vast plainlands, and the Arctic Archipelago. What if we revisited the ways of the ancient seafaring cultures and the desert nomads? Drawing inspiration not only from the speculative but also from the real, the here, the now, the pragmatic and the historic.

Ground Control: An Argument for the End of Human Space Exploration, by Savannah Mandel, published by Chicago Review Press, July 2024, ISBN 978-1-64160-992-0. Available to purchase online and from bookshops.

Ground Control: An Argument for the End of Human Space Exploration, by Savannah Mandel, published by Chicago Review Press, July 2024, ISBN 978-1-64160-992-0. Available to purchase online and from bookshops.

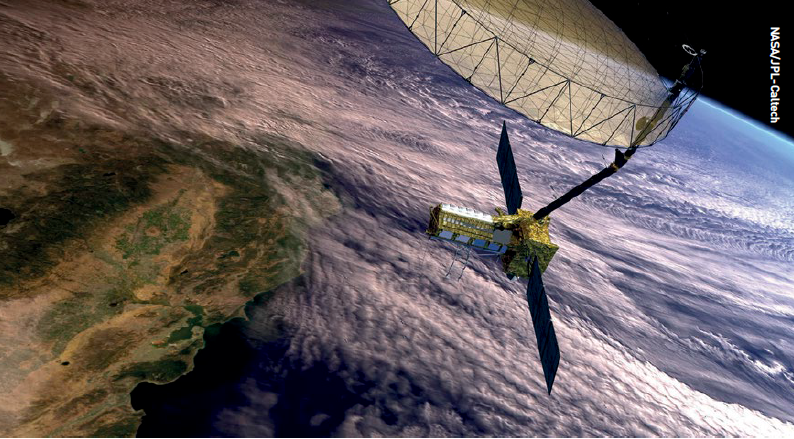

What if we focused on unmanned space travel and let the last astronaut go?

Just like Assata Shakur’s call for collective action - which seeks not only to reform but also to revolutionise and works to upend current systems that fail to value black lives - the Caretaker’s Demand must conjure up a vastly different world without apologising for radical social changes. A world where planet Earth takes priority in research and the collective mission to ensure the sustainability of the human species works from home.

Consider this story a call to arms.

About the author

Savannah Mandel is an anthropologist who researches all things speculative, futuristic and industrial. She is currently a PhD Candidate in Science, Technology and Society at Virginia Tech, holds a MS in Social Anthropology from University College London, MS in Science and Technology Studies from Virginia Tech, and a BA in Anthropology from the University of Florida. She has conducted ethnographic fieldwork at Spaceport America, worked for the commercial spaceflight industry, and is a non-fiction and fiction author.