The United States is profoundly reliant on its ability to use space for its security and its space assets are vital to US defence and intelligence issues. However, the US military is not currently superior to its potential adversaries because it has stronger soldiers, bigger guns or more tanks. It has the upper hand because it can understand better what is taking place in the midst of conflict - what its own forces and those of an enemy are doing amidst the ‘fog of war’. As a result, the United States can employ force around the globe more rapidly, more precisely and more effectively, making it uniquely capable of applying decisive power against an adversary.

Exploitation of space is particularly critical to effective US power projection, as it provides the US military with the ability to operate effectively over global distances, beyond the reach of what US ground-based and aerial assets, limited by range and endurance, can provide. As General John Hyten, Commander of US Air Force Space Command, recently said on CBS’s ‘60 Minutes’, because of space, “we can attack any target on the planet, anytime, anywhere, in any weather”. Thus, Washington’s ability to project credible and effective military power to key regions such as the Western Pacific, Europe and the Middle East relies on space. And this reliance is increasing.

Furthermore, space is also vital for crucial homeland defence and deterrence functions, while space-based assets provide early warning of missile attacks and serve as a crucial component in the command and control system for US forces in the event of war.

Vulnerability

But this reliance is becoming increasingly problematic because potential US adversaries have noticed the degree of US reliance on its space architecture and have been working to threaten US space and space-related systems. Indeed, many observers have noted that these potential opponents judge the space architecture to be the Achilles’ heel of US military power.

Countries like Russia, China, and even nations with more modest capabilities and resources, are gaining the ability to hold US satellites at risk not only through kinetic direct-attack methods such as anti-satellite (ASAT) missiles but also through non-kinetic and more limitable techniques such as jamming, ‘dazzling’, cyber and other electronic methods.

Secrecy and the relative ignorance of space matters among large swathes of the policymaking echelons in the US, Russia and China makes it even more difficult to formulate principles

The result is that the US space architecture is becoming increasingly vulnerable, with US satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) already targetable by a nation such as China and those in higher orbits likely to become similarly exposed soon. China’s 2007 destruction of one of its own weather satellites in LEO demonstrated its ability to hit satellites at that range. Its 2013 test of an ASAT weapon reportedly propelled a missile approximately 18,600 miles into space, just shy of the 22,236 miles at which US satellites in geosynchronous orbit - including essential missile warning and communications satellites - are located.

The US has built an enormously expensive and delicate architecture of space assets upon which it greatly relies for its military pre-eminence and left it increasingly vulnerable to attack or disablement. The question now is what is to be done about it?

In perhaps the most revealing reflection of the DoD’s increased anxiety about the US position in space, the Pentagon recently established an initiative to invest as much as US$8 billion more in space capabilities over the next five years, a serious signal of how gravely the Pentagon considers the problem. As a consequence, it has undertaken a number of internal reviews on how to chart the course for a future US space architecture.

For example, the DoD is making its new satellites more manoeuvrable to evade attack, and rendering them more resistant to jamming, while building a new radar system that will better enable it to track objects in space. The US has also deployed two space surveillance satellites to observe what other countries are doing in geostationary orbit. While these steps represent encouraging progress, the changes will take time to bear fruit, not least because it can take upwards of a decade to develop, build and launch military satellites.

The United States relies so much on space that it is becoming a domain like any other - air, sea, land, and electromagnetic - in which the nation has to compete for access. The US will therefore need to adapt to this emerging reality of reliance on space coupled with growing vulnerability. The question is how best to do so.

Response to threat

One obvious way to address the growing threat to the US space architecture is to seek to defend against it. This can be achieved, in part, by increasing the hardiness of the satellites themselves to enable them to defeat, survive or ride out attack - by providing future satellites with active defences of their own; by deploying additional, dedicated systems to guard satellites and their associated architectures; and by improving space situational awareness (SSA) to better anticipate and understand threats.

Airman Ashley Risk (foreground) and Airman 1st Class Jasper Platt oversee a satellite system procedure at Schriever Air Force Base, Colorado. They are space ground link operators with the 4th Space Operations Squadron

Airman Ashley Risk (foreground) and Airman 1st Class Jasper Platt oversee a satellite system procedure at Schriever Air Force Base, Colorado. They are space ground link operators with the 4th Space Operations Squadron

Alternatively, the threat can be negated or minimised through the development of strike capabilities for use against anti-space assets. These could include kinetic and non-kinetic capabilities to attack an adversary’s systems, as well as the command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) architecture needed to guide and control them.

The problems with this defensive approach lie in the formidable cost and technological difficulties of providing direct defence capabilities for satellites, the inherent fragility of space assets and consequent challenges and limits to increasing their survivability.

Staff Sgt Raymond Polasky points out changes in weather patterns on radar. The weather flight uses tools like weather sensors, satellites and radar to accurately forecast for eight different airframes

Staff Sgt Raymond Polasky points out changes in weather patterns on radar. The weather flight uses tools like weather sensors, satellites and radar to accurately forecast for eight different airframes

Another method for dealing with the increasing threat to the US space architecture is to alter its overall composition to make it a less vulnerable target and improve its resiliency (its ability to recover from damage). The options could include:

- disaggregating the architecture into a larger number of smaller satellites

- building more manoeuvrability into future space assets

- improving SSA to better understand the space environment

- developing future satellites that are more replaceable and thus expendable

- building more redundancy into architecture to diminish points of vulnerability and failure

- streamlining production processes to aid replacement

- improving the nation’s space launch capabilities

- augmenting the ability of the US to inspect, repair and relocate its satellites in orbit.

Indeed, the United States has begun to explore and pursue this avenue. The problem is that solely emphasising resilience without credible ways of defending against or deterring attacks courts failure, as it provides no meaningful disincentive to an adversary, which could simply take the steps required to attack this more resilient US space architecture.

The US needs a more discriminating and flexible deterrent, capable of meeting the intensifying challenge of highly capable potential opponents such as China or Russia

An additional avenue of approach for the United States is to seek to mitigate the consequences of its growing vulnerability in space by relying more on terrestrial and air-breathing assets, such as unmanned aerial vehicles, for a range of missions than orbital assets. Along these lines, last year the US Secretary of Defense called for the military to reduce its dependence on the increasingly vulnerable Global Positioning System (GPS) constellation.

While it makes sense to reduce the dependence of US forces on space assets, this too can only be an element of a broader space strategy. The United States cannot sacrifice its ability to use space in the event of conflict and hope that its military will be remotely as effective as it is today.

Limited war strategy

Unfortunately, there seems to have been little effort to develop a serious defence and deterrent posture for space until recently, and it is not clear that even the commendable recent efforts to strengthen the US space posture are guided by a clear strategic logic. Indeed, Congress was sufficiently concerned by the absence of such a coherent approach and the apparent lack of movement within the executive branch towards this goal that it felt compelled to mandate in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 that the US government develop such a strategy.

The US legacy approach to deterrence of attacks against space assets relied, explicitly or latently, on the threat of a potentially overwhelming retaliation against even limited space attacks. But such a threat is of substantially decreasing credibility. In today’s context, no one really believes that a limited space attack would necessarily or plausibly be a prelude to total nuclear war. Any US space deterrence strategy that is predicated on an all-or-nothing retaliation to space attacks will become increasingly incredible and thus decreasingly effective.

So the US needs a more discriminating and flexible deterrent, capable of meeting the intensifying challenge of highly capable potential opponents such as China or Russia. At the same time, this flexible deterrent must contribute to dissuading such an enemy from striking at the nation’s broader military and civilian space architecture. Put simply, the United States will need to find ways to limit war in space.

The US is also going to want to shape any such conflict in ways that are sustainable and favour American objectives. This means proposing the rules of the fight and then building the assets and strategy to incentivise an adversary’s observance of them. At the same time, to be attractive to Washington, such rules or principles should enable the US to employ force, including in space, in ways that can allow it to attain its basic political objectives. It is, of course, difficult to formulate principles that can both enable one’s own success and attain the consent of one’s adversary.

The DMSP mission is to collect and disseminate global, high-resolution visible and thermal cloud cover imagery, and other critical air, land, sea and space environment data to Department of Defense (DoD) forces and the intelligence community

The DMSP mission is to collect and disseminate global, high-resolution visible and thermal cloud cover imagery, and other critical air, land, sea and space environment data to Department of Defense (DoD) forces and the intelligence community

Moreover, the secrecy that shrouds the programmes of the US, Russia and China, and the relative ignorance of space matters among large swathes of the policymaking echelons in all three countries, makes it even more difficult. Yet we know from history that such limitation of conflict can work, and can work in ways that enable a country prepared to fight a limited war to achieve its aims. Indeed, almost all wars are limited in some way, and all conflicts involving the nuclear-armed states since 1945 have been constrained in some meaningful way or another.

What, then, should such proposed US principles of limitation look like for space in the emerging strategic environment?

The formula for limitation might include the following principles:

- being the first to carry war into space is escalatory and irresponsible

- attacks on or interruptions of strategic space assets would be construed as highly escalatory, and should be presumptively disfavoured

- kinetic attacks that cause lasting damage to humanity’s ability to exploit space abilities are prohibited

- satellites and space assets not directly and substantially involved in a conflict are not legitimate targets for attack

- attacks in space justify responses outside of space.

While these principles and approaches are offered primarily as illustrative examples - more stimulants for discussion than dictates to be etched in stone - they reflect the genre of rules the United States would want to promote. They are informal laws that are sufficiently general and impartial to enlist the support and approbation of third parties, and even potential adversaries, but that also would allow the United States to execute its military operations effectively and ultimately to prevail in a limited conflict.

The more firmly these principles became established, the more the US could adapt its space architecture to them, focusing resiliency, defensive and redundancy efforts more efficiently to exploit the opportunities afforded by a relatively stable set of expectations. Accordingly, the US should seek to gain international diplomatic acceptance of these principles to the greatest extent possible.

Put simply, the United States will need to find ways to limit war in space

However, the United States should not confine its deterrent and defensive efforts to the enforcement of these general norms. In particular, it should seek to develop a strategy and posture to protect even its space assets directly implicated in a conflict using deterrent threats and appropriate defences. What would emerge is a layered or differentiated deterrent posture for space, one with different deterrent threats covering different space systems depending on their involvement in a conflict, their role in strategic missions and other such factors.

US space defences should be effective and cost-efficient enough to make a material difference in adversaries’ potential calculations of how worthwhile attacking US satellites would be. While a full space defence may be unobtainable in the foreseeable future, the better defended, hardier and more resilient the US space architecture is, the more drastic will be the steps an adversary needs to take to materially damage it.

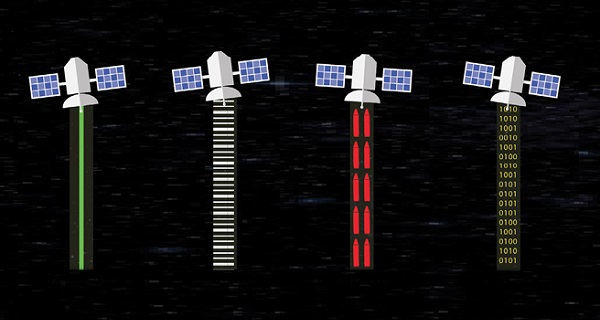

US satellites are at risk from several categories of attack

US satellites are at risk from several categories of attack

This effort should also include an active diplomatic approach, particularly focused on semi-formal and non-treaty-based arms control. Indeed, such activities can play an important part both in promoting stability in space and in advancing specific US interests in this regard.

The US is also going to want to shape any such conflict in ways that are sustainable and favour American objectives

For instance, US diplomacy should seek to promote the norms or rules of a preferred US formula for limitation and advance methods of verification and enforcement. If the US can gain broad diplomatic support for its preferred rules of the road, this can create additional pressure on potential adversaries to observe such norms.

Moreover, Washington should make a special point of encouraging Russia and China to join it in disaggregating strategic from non-strategic space systems in the interests of strategic stability. Additionally, the US could pursue agreements to ban or at least punish the creation of debris in space, particularly from kinetic space attacks.

Policy implications

What does the adoption of such an approach mean in practice, in terms of changes to existing US deployments, strategy and organisation? It is beyond the scope or ability of this article to make recommendations regarding specific capabilities, but the following propositions can be made.

To further its interests in space security, the United States should:

- build a future space architecture that is prepared for war - and particularly for limitable war

- develop effective but limited forms of space attack, particularly non-kinetic ones that do not result in space debris

- procure and emplace space defences on satellites in a way that raises the costs, risks and uncertainty an adversary would encounter by striking the system

- strive to segregate its strategic space architecture from other functions, especially conventional war-fighting functions

- develop deliberate and adaptive planning capabilities for conflict in and affecting space and highly capable command and control systems

- understand what the diplomatic ‘market will bear’ and seek agreement to preferred US principles of how a war in space could acceptably unfold

- seek to influence space-related technology development in ways favourable to this strategy through engagement with allies, cooperation with industry, export controls, and the like

- seek to change perceptions of what the interests of the US and its allies require - and what is legitimate - with respect to defences and conflict in space.

As a basic principle, the United States should build a space architecture designed to conform to this defence strategy. This means that no future space assets should be built without the defensive and resiliency capabilities needed to integrate them into such an architecture, even at the cost of some sacrifice in capability. In brief, the future US space architecture should be one prepared for war - and particularly for limited war.

A Global Positioning System IIF-series satellite undergoes final encapsulation inside a four-metre diameter protective payload fairing. The GPS IIF system provides improved navigational accuracy through advanced atomic clocks, a longer design life than previous GPS satellites, and a third operational civil signal (L5) that benefits commercial aviation and safety-of-life applications.

A Global Positioning System IIF-series satellite undergoes final encapsulation inside a four-metre diameter protective payload fairing. The GPS IIF system provides improved navigational accuracy through advanced atomic clocks, a longer design life than previous GPS satellites, and a third operational civil signal (L5) that benefits commercial aviation and safety-of-life applications.

The limited war strategy outlined here is one that, while acknowledging the reality of vulnerability and scarcity of resources, proposes a way of constructing a space defence and deterrence posture. It is built around a preferred formula of limitation, enforced by intelligently-targeted investments in retaliatory capabilities and space defences, and strengthened by efforts to improve the resilience and redundancy, lower the costs and minimise the fragility of the US space architecture.