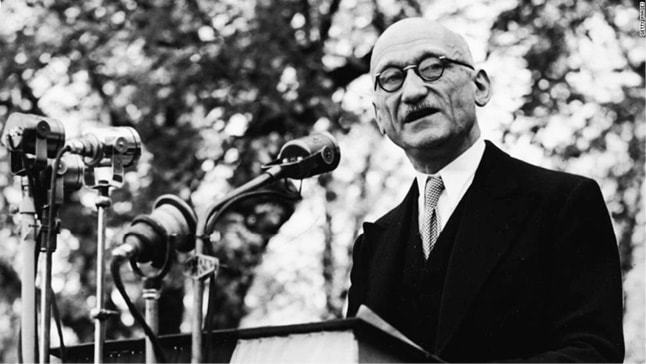

n May 1950, the French minister of foreign affairs made a speech from the l’Horloge du Quai d’Orsay in Paris, in which he famously launched the European coal and steel community project.

n May 1950, the French minister of foreign affairs made a speech from the l’Horloge du Quai d’Orsay in Paris, in which he famously launched the European coal and steel community project.

Born to a French father, who became a German national after the war in 1870, and a mother from Luxembourg who became a French citizen after the treaty of Versailles in 1919, he was a member of the first government of Vichy before escaping to the ‘free zone’.

As a member of French parliament since 1946 and drawing on his rich experience of life, Schumann asserted: “World peace can only be safeguarded with the efforts of its creators at the level of the dangers that threatens it.” He spoke of the necessity to construct a united Europe in order to assure peace in the world - and discussed the efforts needed to get there.

His proposal was specific and began by placing the joint production of French and German coal and steel under a joint high-level authority in an organisation which is open to participation of the other European countries. “We have,” concluded the French minister, “to not only make war unthinkable but also physically impossible.”

Space is not only defined by its physical characteristics but also by its technical characteristics

This Schumann speech is considered one of the founding texts of Europe. And reading it again brings to mind one single undertaking in which many European countries have engaged for more than 50 years - the exploration and exploitation of space.

In its Dictionnaire de spatiologie, the international council of the French language defines space as ‘a short form of the usual extra atmospheric space’ and ‘the domain of human activities which are linked to the extra atmospheric space’.

But there is another interesting definition - because space is not only defined by its physical characteristics but also by its technical characteristics. In other words, space is not only the territory which starts at a theoretical altitude of 100 km above Earth’s surface - space also encompasses all what humankind do there and what they do with it.

One can also say that space does not have a precise definition nor a precise boundary because, fundamentally, there is a problem in giving such a boundary to an ‘atmosphere’. And with the prospect of seeing the cosmic horizon extend further and further as we continue to explore and make use of space, surely this is the same with Europe and peace?

French politician Robert Schuman is regarded as one of the founding fathers of the European Union, and (below) Charles De Gaulle.

French politician Robert Schuman is regarded as one of the founding fathers of the European Union, and (below) Charles De Gaulle.

Charles de Gaulle, who created the French national space agency (CNES) in December 1961, also knew the difference between running after a theoretical dream and acting positively to make it happen.

He was astute enough to perceive the inevitability of a political dimension to the construction of Europe, initially conceived only in economic terms. And he displayed contempt to those who confined themselves to a Europe of words, tirading during a speech in 1965 “Europe! Europe! Europe! - bleated like a goat” which in itself, he stated, would not lead to anything meaningful. His view was that the ‘construction’ of Europe would only find its true significance in the creation of close political co-operation between the states of Europe.

In space terms, the failure of the Europa programme - developed by the European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO), a former European space research organisation - and the subsequent success of the Ariane programme are testimony of the requirements to which people and institutions have to surrender themselves when they engage in the kind of direction and ambition - as defined by Schumann - to formulate European cooperation for the service of peace.

Ultimately, the Europa programme was too decentralised, too abstract and too defused, and so one has to both prefer and accept a centralised mode of operation and a focus of efforts around one single project with a defined industrial leadership - as shown by the success of the European commission for coal and steel (ECCS) and Europe’s Ariane rocket.

One has to both prefer and accept a centralised mode of operation and a focus of efforts around one single project with a defined industrial leadership

One also needs a complicity of participants who are willing, charismatic and daring for an objective that is both clear and ambitious - peace in Europe after two World Wars in less than half a century. For an objective this challenging and ambitious there is a plethora of actions and decisions to overcome and be made, not to mention ambushes designed to bring about failure.

Of course, Europe without its ‘borders’ but with its plethora of nationalities, institutions, organisations, laws and legislators has still not achieved the ultimate goal of its mission, so eloquently proposed by Schumann and the other founding fathers of Europe.

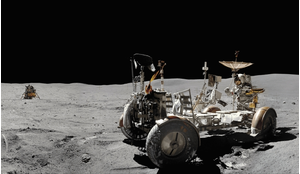

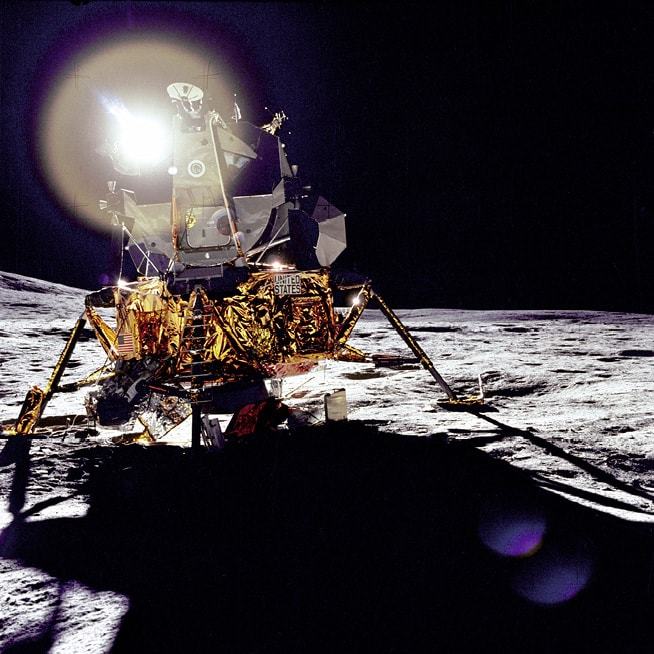

Programmes like Apollo, along with more recent space missions, have changed humanity and society in an irreversible way.

Programmes like Apollo, along with more recent space missions, have changed humanity and society in an irreversible way.

High above our heads the space successes of yesterday are put into question by other emerging powers whether public or private - and for Ariane to survive it will have to confront new challenges in finding both its technical and commercial raison d’etre. There are many reasons for concern and it would be vain and even dangerous to ignore them. But we should not easily forget how far we have already travelled along this road.

So, let’s think again about the history of space and recall the words of Neil Armstrong on the 21 July 1969, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind”. Has that small step been effectively followed by a giant leap? Some would say not, simply because mankind has not returned to the Moon for 45 years. But do not forget how the missions of Apollo - and more recent space programmes - have changed our humanity and society in an irreversible way, perhaps in the process forcing us to accomplish not one but many giant leaps?

It is wrong, as some would suggest, to pretend that images of Earth brought to us by American astronauts journeying to the Moon gave birth to the ‘green’ movement and were solely responsible for raising environmental awareness. But nevertheless these images were an effective catalyst which certainly reinforced the birth of the ecologist movement.

Never before has humanity had such common consciousness about what it is like to live in a real cosmic oasis - beautiful, fragile and endangered. Today, it is hardly relevant that the first observation satellites were launched with the goal of military espionage, the surveillance of both enemies and friends. But thanks to them the tensions between the East and West, so powerful in the 1980s, have not led to a new world conflict or nuclear war.

Undoubtedly, we needed this first military-led step before arriving at the civil Earth observation satellites, along with the GPS satellites and the telecom satellites, all of which have revolutionised daily life on Earth. With programmes like Copernicus and Galileo, Europe continues to move along this path.

It is right to be aware of the dual military and civil character of space activities - and Europe’s approach is right in this regard. It is necessary to take stock of the evolution and even the revolution provoked by these technologies. The time where it was possible to ignore, or even to pretend to ignore, what was happening at 100’s of km or even at tens of km from home has gone.

There are many reasons for concern and it would be vain and even dangerous to ignore them. But we should not easily forget how far we have already travelled along this road.

To justify our incapability or unwillingness to act, our governments and every one of us can no longer plead ‘we did not know’. Space technologies have contributed to the birth of a common responsibility towards each other. And the future of Europe, the Europe of Copernicus and Galileo, will only happen if we take this responsibility seriously.

Even if we have to give in, at least partially, to the dual character of space, our laws implore us to forsake turning Earth orbit into a military zone, whilst at the same time recognising we can still derive benefits from military observation satellites.

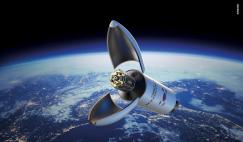

The third liftoff of a heavy-lift Ariane 5 in 2016 carrying EchoStar XVIII and BRIsat.

The third liftoff of a heavy-lift Ariane 5 in 2016 carrying EchoStar XVIII and BRIsat.

For Europe’s aspirations in human spaceflight, cooperation as a partner in the International Space Station is the most evident illustration. But I am dreaming of a day in the future when a man or a woman from Europe will wear a blue star flag on their spacesuit rather than their national flag. Do we need to wait until they put foot on the Moon or on Mars?

An Ariane rocket on its launch pad in French Guiana - the programme can be viewed as a symbol of European cooperation.

An Ariane rocket on its launch pad in French Guiana - the programme can be viewed as a symbol of European cooperation.

I am ready to believe because it is only in confrontation with the unknown that humans can agree to surpass the sanctity of their own national identity - protected, preserved and sometimes defended - and have access to another level of themselves, and a new identity.

Socrates taught his disciples to know themselves in order to know the universe and the gods - and he was right when he spoke against the priests of Delphi in Ancient Greece. On the front of their temple it was first written ‘know thyself’, and they had added, ‘and leave the universe to gods’.

Ultimately, I believe there exists a unique bond between the human will and the decision to confront space, both in terms of locations and technologies, and in doing so we can embrace the possibility of expanding our personal knowledge and awareness. I am convinced that this kind of understanding establishes a way to respond to the invitation of Robert Schumann in constructing a peaceful and cooperative Europe. And, just as this is the case for the nations of Europe, it is also the same for space. Ultimately it is about what we do in it and what we do with it.

Jacques Arnould is an engineer in agronomy, historian of sciences and a theologian. He takes an active interest in the interrelation between science, culture and religion. He works with the French Space Agency (CNES) where he is an expert in charge of ethical aspect of space activities.

If you would like to submit an opinion, letter or comment article to ROOM please contact or send via email to: Clive Simpson, Managing Editor - clive_simpson@room.eu.com