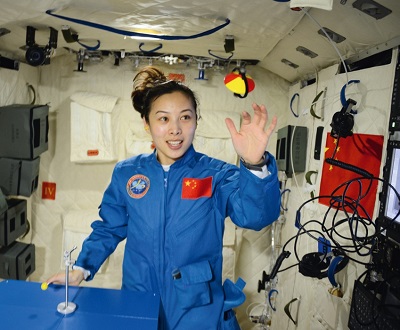

My name is Wang Yaping and I am a taikonaut. Fifty-one years ago, Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space, and a door was opened. One after another, women began going into space, setting a trend. Their stories inspired other women. So, on behalf of all those who followed in Tereshkova’s footsteps, I’d like to honour our predecessors. After 51 years, nearly 60 women have gone to space, including two female taikonauts, Liu Yang and myself.

Many people have asked me why, as women, we feel the need to join men in space. The answer is that without the participation of women, the human space programme is incomplete, the space family is missing something.

Women are just as capable of taking responsibility, energizing their colleagues, and taking on serious and tough missions with spirit and harmony. Not to mention the fact that the participation of women makes it possible to study the physical and psychological differences between how men and women are affected by going into space. Last but not the least, my body weight is less than most male taikonauts, which makes me a fuel-saver.

A new kind of teacher

We all have different dreams as children. I was born in a beautiful small village in northern China, and when I was young, my world was small. To my eyes, the sky was merely a limited space, surrounded by mountains. The sky was a home for birds, not me. I never thought the sky would call to me. My dream was much more simple: to go beyond the mountains and to pay back all that my parents had given me.

I never thought the sky would call to me

At the time, I thought I would be a lawyer or a teacher. But then I was recruited to be a pilot and later selected into the taikonaut corps. I ended up very far away from the realm of lawyers, but I am now closer to the dream of being a teacher – a special kind of teacher, one who brings knowledge of space.

A woman in space

Becoming a qualified taikonaut is never easy, especially for a woman. In our daily life here on Earth, the standards and requirements for male and female are different in physical labour and in sports. But in space, you can’t catch a break simply for being a woman. So the training subjects, training contents and test standards for women are almost identical to those of male taikonauts. That means that we women often have it much harder. The facts, however, speak for themselves: what male astronauts can do, we female astronauts can also do. And maybe it was due to my “manly” style in training that our commander Nie Haisheng told the media during an interview, “Yaping is a nice girl, we always want to take care of her. But it seems she doesn’t need any help.”

Neil Armstrong famously said during his moon landing, “That’s one small step for a man…One giant leap for mankind.” But I also feel that one small step in space means a huge leap to an individual life. The experience, the feeling and the value given to our life by spaceflight is precious and irreplaceable. In this sense, no flight is ordinary. I had all of that on my mind when, at 17:38 on June 11, 2013, when the command of “Ignition” was spoken, my crewmate Nie Haisheng, Zhang Xiaoguang and I started our space journey as the Shenzhou 10 crew.

Teaching space class

My major responsibilities were space class and day-to-day care of our crewmembers. Of course, I was also responsible for routine spacecraft status monitoring, equipment operation, and space experiments, not to mention manual rendezvous and docking. The space class was unique, however – it was the first such educational endeavour for China’s human space mission and it was broadcast live not only in China but all over the world. The responsibility of being the primary teacher fell on my shoulders. This was not just an honour, it also presented a great challenge to me.

The spinning top experiment was inspired by Wang’s grandparents

The spinning top experiment was inspired by Wang’s grandparents

It took great effort to select the kind of experiments that I wanted to show in space class. The idea is to have something that would be interesting to children, to both expand their horizons and improve their knowledge. We also have to consider the prospect of outreach, visualisation and implementation of concepts that people on Earth can relate to. For instance, the spinning top is one of the few toys of the generation of my grandparents, as far as I know. It was a great source of entertainment for them. Even today, many children still like them. We know how the spinning top behaves on the ground but how will it do in space? Because I know that many people back home would be interested in such a simple but fun subject for space class, I selected it.

Another good example for a space class topic is the mass measurement experiment. Because of the restrictions on lift-off mass, the number of teaching apparatuses onboard is always limited. So we adopted the in-situ approach. We used the mass measurement device left in Tiangong-1 to measure our body weight changes in space and dedicated a space class to this.

When teaching was assigned to me, I was excited and nervous. I have never been a teacher before and I was not entirely confident in my abilities. To make the space class interesting, I spared no effort. For instance, I watched teaching videos made by our foreign colleagues and studied the teaching methods and skills of professional teachers. Moreover, I tried to change my role from teacher to student, watch my teaching videos and pinpoint my own shortcomings.

Becoming a qualified taikonaut is never easy, especially for a woman

On 20 June 2013, as the primary teacher of space class, I spent 40 unforgettable minutes with over 60 million primary and middle school students and teachers from over 80 thousand schools all over China on the 300 km earth orbit. I demonstrated magical physical phenomena in micro-gravity and successfully conducted five small experiments on the movement of objects and liquid surface tension. It was a great way to show the children the world we experience in space.

The space class is unique for China

When conducting experiments in space for the first time, I was curious and nervous, even though I knew what the outcome was supposed to be. This was because all the phenomena were also seen and experienced by me for the first time.

Teaching in zero gravity

On-orbit demonstrations are quite different to what we’re used to on the ground. The operation skill and the magnitude of strength are the keys. Making a water ball in space is a good example: you have to have the water membrane at just the right thickness, you have to make it beautiful as opposed to misshapen. There was a lot of trial and error involved in that. In addition, the micro-gravity environment brought more difficulty to the space class. I had to work hard at keeping my balance while doing my demonstrations.

Back on Earth

After return to Earth, I established teacher-student relations with many children and received many letters from them. One child wrote to me, “Teacher Wang, I saw you sleep in the sleeping bag just like a sausage. It was very funny.” Another child wrote, “Teacher Wang, I saw you floating in Tiangong, like Chang-e, and I really envy you.” Another one wrote, “Teacher Wang, you have given me a new dream, and I am slowly climbing to the top of a tree like a caterpillar. I believe one day I will climb up and like you, turn into a butterfly, fly to the sky and realise my dream.”

Zero gravity was both challenging and amusing

Zero gravity was both challenging and amusing

I was very touched that many children wrote at the end of their letter things like, “I will study hard and I want to be an astronaut in the future, to explore the beauty of space. I want to be of use to our country and to our world.” Every time I saw such words, I was deeply moved.

Each year, during the summer holiday, students from all over China, including those from Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau, come to Beijing space city to take part in the Astronaut Experience Camp. They can experience some of the training courses of taikonauts such as taking the IVA spacesuit on and off, dropping from the escape tower, tasting space food, trying the rotation chair and talking with taikonauts face-to-face. They learn a lot, and come to feel both the pain and the joy of being in the space programme.

After my return to Earth, I have been to dozens of schools. I spoke to many children and saw firsthand their yearning for a new world. Children have an unlimited imagination, which, in turn, makes for unlimited motivation. I never expected that a short space class could have such a great impact on them.

I have to say that it changed me too. I love science, outreach programmes, and love every aspect related to space science. I even felt that being a teacher while up in space brought me more honour than my career as a taikonaut.

Just the beginning

I still remember how someone asked me “what is your next dream?” during a media interview after my return. My dream is to go further and further in this career. Yes, this is just the beginning. Space exploration is endless. I hope that I can make more contributions to human space flight and outreach programmes, taking advantage of my space class experience and the identity of an astronaut. If I could, I would be a space teacher forever.

I believe if I have the chance to return to space, I will communicate with children abroad and learn what ideas they have. During my mission, I communicated with the first space teacher, Barbara Morgan. I hope that we can have face-to-face chats to discuss the development and cooperation.

In China, human space flight and the outreach programmes will be merged. In the future, various outreach initiatives such as call for flight experiment ideas and mission logo contests will all be carried out. I believe with our efforts, more people will feel closer to a new world beyond our planet.

I would like to end with a quote from one of my own space classes: “The space dream will never be weightless, and the science dream has endless energy.”