Humanity’s desire to go into space is dictated by evolution. Far from being strange or aberrant, it is the natural next step for our species. Yet our cosmic expansion is bound to run up against barriers, which could include the rise of a new, post-human species to take our place. As radical as this might sound, it’s nowhere near as problematic as the possibility that the Universe is a fractal, and all life within it is doomed to fail.

Today, the idea that humanity is at the centre of all creation – the anthropocentric view – continues to dominate. Yet the idea of universal evolution can cure that. Humanity is not the main goal, nor the final step in evolution – it’s merely an intermediate stage.

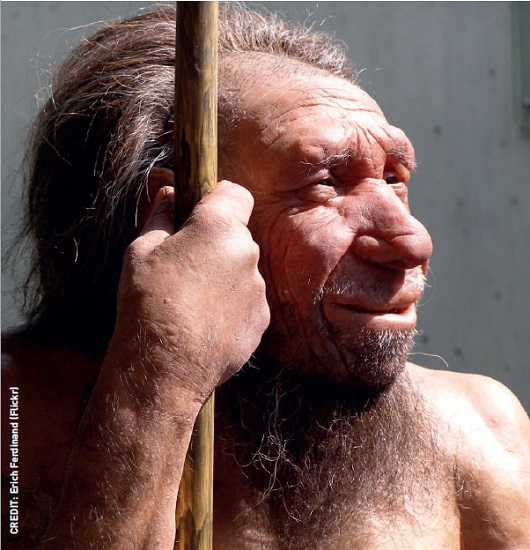

Evolution doesn’t ‘care’ about humanity’s interests, or the interests of any species. At any given time, evolution favours those species that are best equipped to survive. For a time, evolution’s ‘idol’ was the Neanderthal, which was replaced by what we know today as Homo sapiens. Tomorrow, humans will be replaced by something else.

- The main demands of the march of evolution, what we might call evolution’s vector are as follows:

- Increase in complexity

- Increase in diversity

- Intensifications of metabolisms/interactions

- Intensification of cycles

- Growth of structural integrity

- Growth of open systems (the rising role of interaction with the environment)

- Growth in the fractality of evolving systems

Following evolution’s vector isn’t everything. Evolution takes a given set of consequences and wrings out all possibilities, forcing evolving systems to grow more complex and diversified. But what does this really mean? Thanks to Alexei Severtsov (1866-1936), the following idea became rooted in biological evolution: progressive refinements differ from un-progressive ones in that the former pave the way for more refinements.

The cluster of galaxies Abell 1689. Life in our observable universe is doomed if the Universe is a real fractal.

The cluster of galaxies Abell 1689. Life in our observable universe is doomed if the Universe is a real fractal.

If we generalise that we reach the principle of minimax in evolution: in the course of evolution, the intensity of metabolism grows, leading to subsequent intensifications of metabolism.

In my view, the so-called “meaning of life” has to do with following evolution’s vector – this goes for individuals, societies, and humanity as a whole. If we ignore the vector, we will perish or be relegated to the margins. Today, humanity is the evolutionary pinnacle on Earth precisely because it follows the vector.

One of the main characteristics of universal evolution is the expansion of the most highly advanced evolutionary forms that also follow evolution’s vector. This is where humanity’s desire to constantly expand the zone of its evolutionary achievements comes from. Humanity has ‘conquered’ the Earth, but what we might call the “law of expansion” forces humanity to look towards space to further widen the scope of its successes.

Yet humanity will not triumphantly go forth across the never-ending Universe, because its cosmic expansion will be checked in space and time by two barriers.

The post-human stage of evolution

In 1975, Benoit Mandelbrot published his book Les Objets Fractals, which opened our eyes to the fractal structure of the world. For centuries, science thought of material bodies as more or less uninterrupted objects. Mandelbrot showed us that fractal structures dominate, and that they are characterized by extreme roughness.

The phenomenon of fractal evolution is becoming better known. A simple explanation for it involves looking at a tree, with its irregular structure. We all know about the tree of organic evolution – this same tree exists in the more general sense of universal evolution.

Fractal evolution means that evolution occurs via a cascade of branching points, within which alternative evolutionary branches are conceived. This idea is one of the main points of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s Le Phenomene Humain (The Phenomenon of Man) (1955).

Humanity has ‘conquered’ the Earth, but what we might call the “law of expansion” forces humanity to look towards space to further widen the scope of its successes.

Intelligent life is also represented on the tree - one of the branches is humanity. The varieties of intelligent life are many, and possibly go beyond our understanding. According to his fellow academic Alexander Spirin, the Soviet academic Boris Kadomtsev once said that complex cosmic systems could potentially be capable of abstraction and predicting their own future. Vladimir Lefebvre’s book The Cosmic Subject (1996) presents a similar idea of an intelligence of cosmic proportions. According to Lefebvre, cosmic object SS433 - a microquasar - could potentially be such a subject. Lefebvre thinks its structure is magneto-plasmic, and he sees coded musical C-major and C-minor scales in its emissions.

Neanderthals couldn’t compete with homo sapiens – will the same happen to us when post-human species evolve?

Neanderthals couldn’t compete with homo sapiens – will the same happen to us when post-human species evolve?

The nature of Kadmotsev and Lefebvre’s thoughts is extremely speculative, but it’s possible that self-aware macro-creatures exist in the Universe. Cognitive creatures on Earth are extremely diverse, and that’s within a narrow range of conditions. So why can’t life be more diverse in more diverse conditions, both within our own Metagalaxy (the entire system of galaxies making up the large-scale structure of the observable universe) and the rest of the Universe, often called the multiverse, beyond that?

Correlating the idea of the unlimited diversity of life with the idea of universal evolution, it’s inevitable that the human stage of civilisation will evolve to the post-human, assuming civilisation on Earth is not destroyed before then.

Post-humanity will be the next intermediary evolutionary stage, but we don’t know what form it will take. Perhaps a different organic species will replace humans. That may not happen, just like it didn’t happen to prokaryotic organisms. These single-celled organisms didn’t disappear when eukaryotic organisms appeared on Earth. Something similar could occur when we move to the stage of post-humanity, which could continue to evolve from human individuals.

Yet post-human species could take more radical forms as far as humanity is concerned. Indeed, it’s possible that the post-human future will arise as the result of something that is completely unknown to us today.

It’s hard to say how humanity should behave when this, in my view inevitable, future arrives. On the one hand, resistance against the march of evolution is suicidal. On the other, acting according to evolution in such circumstances would mean helping post-humanity to quickly dominate all areas of life and marginalise humanity – or even liquidate us.

Similar situations have occurred many times throughout our history. Look at what happened when Old World conquerors encountered the Native Americans. From today’s standpoint, what would have been the best course of action for the Native Americans? War? Cooperation? Quick integration into a foreign civilisation?

The issue with post-humanity also has to do with the fact that we don’t know when humanity might encounter it. After all, we don’t know whether or not there is intelligent life in the multiverse besides that on Earth. I believe that within the boundless space of the multiverse other intelligent life does exist, and that the number of so-called ‘hotbeds’ of intelligent life is similarly limitless.

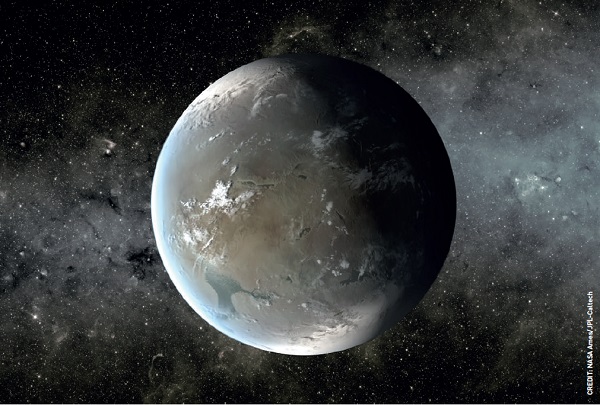

The real question is: how far away are such hotbeds from one another? If the Earth’s biosphere is unique to our observable universe, we are doomed to isolation. But if our observable universe contains many such biospheres, there would be a real possibility of encountering fellow intelligent beings. In the former scenario, we will encounter post-humanity when we give rise to it ourselves. In the latter, an encounter with post-humanity, which will stop our cosmic expansion, could occur earlier.

The discovery of Earth-like planets by the Kepler Space Telescope, adds weight to the argument that intelligent life is widespread

The discovery of Earth-like planets by the Kepler Space Telescope, adds weight to the argument that intelligent life is widespread

This barrier on the path of humanity’s cosmic expansion is not impermeable. Even after encountering post-humanity, we won’t totally disappear. The Neanderthals didn’t – they gave us a certain amount of their genes to pass on. And neither did the Native Americans, who continue to contribute to human civilisation.

However, there is a barrier to our expansion across the cosmos that we cannot get around.

Why intelligent life may be doomed

Fractals have one strange quality that I mentioned in my book Mechanics and Irreversibility (1996) and discussed at length in ‘The phenomenon of humanity against the backdrop of universal evolution’ (2005). If you measure a ‘real’ fractal using ‘cubes’ of topological dimension, i.e. the dimension of space where the fractal is located, the answer you get is zero. This quality only applies to ‘real’ fractals, i.e. fractals in the strict mathematical sense of the word, which appear only in computational exercises. It does not concern material fractals that exist in three-dimensional spaces, such as ash, trees, lungs and galaxies.

… there is a barrier to our expansion across the cosmos that we cannot get around.

It’s best illustrated with a simple example. Imagine an infinitely thin piece of paper. We use it to fill up a room by cutting it into infinitely thin strips, which are then ripped into “points”. These pieces of paper are two-dimensional and each has zero mass. Understandably, we can’t really fill up a three-dimensional space with it – the paper creates a structure of zero density that’s empty everywhere. This paper structure is equivalent to a ‘real’ fractal.

A ‘real’ fractal must retain its qualities no matter how many small measuring cubes are used on it. This requirement isn’t really an obstacle as far as the boundless multiverse is concerned. From the point of view of an observer, and the world that he observes (both of which approach infinity), the sizes of the limited measuring cubes we are using approach zero.

The question is this – is the Universe fractal in the real sense, being the only ‘real’ material fractal? Judging by what I know, the answer is yes. The hypothesis of the fractal universe correlates with the results of our observations.

The average density of cosmic matter falls rapidly to mind-bogglingly tiny quantities as we move outwards from the Sun, which has a density of 1.4 g/cm3) to the Solar System (10-12 g/cm3), the Galaxy (10-24 g/cm3) and the observable universe (2 x 10-31 g/cm3). We can assume that with an unlimited growth of the volume of fragments of the Universe, their density approaches zero.

The hypothesis of a fractal universe results in this:

A fractal universe is limitless (only a limitless Universe could be a ‘real’ fractal)

A fractal universe has a density of zero

Because a fractal universe has a density of zero, the Universe as a whole can neither expand nor contract. Therefore the Big Bang was experienced not by the whole Universe, but by our own observable universe. A fractal universe cannot evolve.

This last point is crucial. Using the theory of the Big Bang, let’s look at what happens if our observable universe, affected by gravity, begins to contract. Sooner or later, all complex material forms that arose within it as the result of its expansion, including organic life and societies, would become hot plasma. The same would hold true of other contracting Metagalaxies.

Eukaryotic organisms like this phytoplankton didn’t replace prokaryotic organisms on Earth

Eukaryotic organisms like this phytoplankton didn’t replace prokaryotic organisms on Earth

With the fractal universe having a density of zero, the processes of contraction and expansion of metagalaxies and other cosmic macrosystems could not cause one to prevail over the other. This means that the evolution of the whole of a fractal universe is impossible – the results of local evolutions in cosmic macrosystems are lost when the process of contraction begins.

Expanding and contracting metagalaxies and other macrosystems in a fractal universe are not some improbable fluctuations in an equilibrium-based universe, as portrayed by Ludwig Boltzmann’s fluctuation model. Almost the whole of the Universe is composed of them. Intelligent life, we can presume, is the natural result of evolution occurring in expanding metagalaxies. A fractal universe is teeming with life. Yet the phenomenon of life in such a Universe is fatally localised in both time and space. Everywhere, life is doomed to destruction. This, sadly, applies to the whole of human civilisation and all of our cosmic expansion plans.

What I am saying is terrifying, but also familiar.

What I am saying is terrifying, but also familiar. All human individuals are doomed to die, but this doesn’t prevent us living out our lives, with all of their sad and happy moments. There is just one serious difference. Individuals have a chance to continue on via their descendants, and by contributing to the evolution of their society and humanity, and all life in the observable universe. But life as it exists on the metagalactic level has no such chance – it simply disappears, leaving nothing behind. If life occurs again in the observable universe when it expands, it will start from a blank slate and have no knowledge of what came before.

Perhaps you disagree. You might say that expansion of some metagalaxies isn’t followed by contraction. Instead, their contents are spread out in the spaces between other metagalaxies. I believe this is impossible, because it would mean that the process of expansion prevails over the process of contraction, which is impossible in a fractal universe. Any matter from metagalaxies that have ‘refused’ to contract will be picked up by other metagalaxies and go through the process of expansion and contraction.

Of course, all of this rests upon the hypothesis of a fractal universe being correct. The question is: is it correct after all?