With strong evidence to suggest that a vast, global, salty ocean is hiding under its thick, icy crust, Jupiter’s moon Europa is high on the list of objects to study for signs of life beyond Earth, even more so now, as new research shows that volcanic activity may have occurred on the moon’s seafloor in the recent past – and may still be happening.

Using 3D computer modelling to study Europa’s interior, a team of international scientists have investigated how the moon’s internal heat production could have melted its silicate mantle through time to feed volcanoes on the ocean floor.

Wedged between Io and Ganymede, Europa is kept warm internally through radiogenic heating – heat generated by the decay of radioactive isotopes – and via a process called tidal friction.

This latter process is caused by the massive gravitational pull exerted by Jupiter. The pushing and pulling motions the moon experiences as it orbits the gas giant causes its interior to flex. This generates heat and the more the moon’s interior flexes, the more heat is produced.

This heat needs to go somewhere and on Europa it helps melt the rocky layer called a mantle, causing magma to spill out onto the seafloor as volcanoes.

Knowing how much magmatic activity has occurred on the seafloor is key to determining how hospitable an environment is to life. This is because long-lived energy sources give more opportunity for potential life to have developed; especially in the dark recesses of the ocean where sunlight cannot reach.

Take for example hydrothermal systems at the bottom of Earth’s oceans, the so called ‘black smokers”.

Like hot springs and geysers on land, hydrothermal vents form in volcanically active areas often on mid-ocean ridges, where Earth’s tectonic plates are spreading apart.

Discovered in the late 70s, black smokers where found to contain a whole entirely different ecosystem of organisms that we never knew about.

Instead of using sunlight to draw energy from, creatures such as tube worms, shrimps and crabs were feeding off chemical energy driven by interactions between ocean water that had been heated by underlying magma.

This discovery fundamentally changed our understanding of how life could develop on Earth.

To understand if a scenario such as that could be occurring in the oceans of Europa, a team led by Marie Běhounková of Charles University in the Czech Republic, looked at how volcanic activity may have evolved over time on the moon’s seafloor.

Using a three-dimensional numerical model, Běhounková and colleagues found that magmatic activity can continue during most of Europa's history even though it progressively decays as the interior cools down.

“The predicted magmatic pulses should be accompanied by the release of volatiles that may impact the oceanic chemistry and may be detected by upcoming spacecraft missions,” say the authors in their recent paper submitted to Geophysical Research Letters.

The team further predicted that volcanic activity is most likely to occur near Europa’s poles – the latitudes where the most heat is generated.

“Our findings provide additional evidence that Europa’s subsurface ocean may be an environment suitable for the emergence of life,” Běhounková said. “Europa is one of the rare planetary bodies that might have maintained volcanic activity over billions of years, and possibly the only one beyond Earth that has large water reservoirs and a long-lived source of energy.”

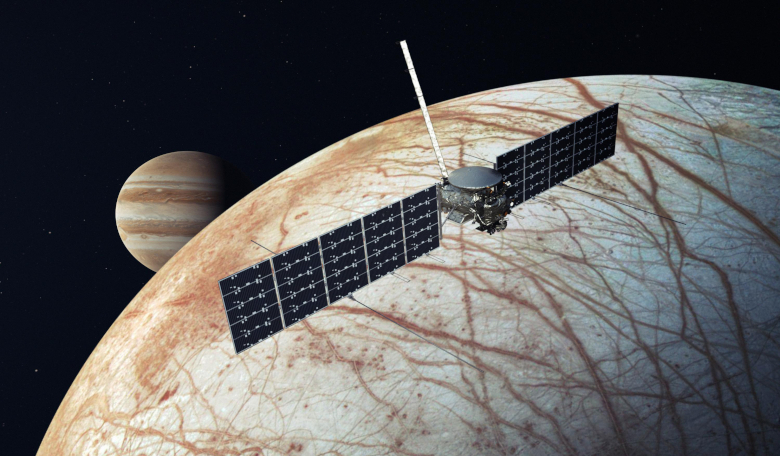

Běhounková and colleagues findings could be tested by NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission, which is targeting a launch in 2024.

Set to reach its target in 2030, the spacecraft will orbit Jupiter and perform dozens of close flybys of Europa to map the moon, sample its thin atmosphere and to investigate its composition.

The surface and atmosphere observations collected by the Clipper will give scientists a chance to learn more about the moon’s interior ocean that in turn could help shed light on whether the right conditions for life are lurking below Europa’s frozen exterior.