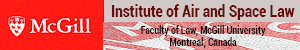

After failing to rendezvous with the International Space Station as planned during Starliner’s first orbital flight test in December last year, an independent review carried out to determine what went wrong has found, “two critical software defects” that were not detected ahead of flight despite multiple safeguards, says a statement by the agency, one of which could have had serious connotations for the spaceship during reentry.

Following Starliner’s troubled Orbital Flight Test (OFT) mission late last year, a joint investigation team consisting of NASA and Boeing officials was established in January tasked with examining the primary issues that occurred during the test flight.

At the time of the incident it was revealed by mission officials that problems with Starliner's onboard timer was behind the capsule consuming more fuel than anticipated, thus preventing Starliner from docking with the space station.

Although engineers regained control of the situation and put the spacecraft into a safe orbit, a further review of other critical components led engineers to uncover a “valve mapping software issue,” within the Service Module (SM) Disposal Sequence said the agency in a teleconference on 7 February.

The service module contains the spacecraft's support systems and is supposed to detach prior to re-entry. Had the problem not been caught and fixed via a software patch before the spacecraft returned to Earth, the cylindrical service module’s thrusters could have fired in the wrong sequence, sending it back into the crew module and possibly triggering a problematic collision of the two components.

"The thrusters' uneven firing would cause the service module, which is a piece of a cylinder, to come away from the crew module and recontact, or bump back into it," Jim Chilton, senior vice president for Boeing Space and Launch, said during the teleconference, adding that "bad things" can happen as a result of that eventuality.

"While this anomaly was corrected in flight, if it had gone uncorrected it would have led to erroneous thruster firing and uncontrolled motion during SM separation for deorbit, with the potential for catastrophic spacecraft failure," said Paul Hill, a former flight director and member of NASA's Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel.

“While both errors could have led to risk of spacecraft loss, the actions of the NASA-Boeing team were able to correct the issues and return the Starliner spacecraft safely to Earth,” says the statement by NASA.

In addition to the two software issues, a poor communications link which impeded the Flight Control team’s ability to command and control the vehicle also contributed to the problems Starliner faced on the test flight.

The investigative review team is still working to determine the exact cause of this interference, but it appears to be associated with cell phone towers, John Mulholland, vice president and program manager of Boeing's Starliner program, said during the teleconference.

This latest failure from Boeing, which is still reeling from two fatal crashes of its 737 Max aircraft, has called into question the company’s safety procedures, and as such, the safety panel has recommended several reviews of the aerospace giant. "The panel has a larger concern with the rigor of Boeing's verification processes," Hill said.

“We want to understand what the culture is at Boeing, that may have led to that,” said Douglas Loverro, a senior NASA official, adding that multiple errors also pointed to "insufficient" oversight by his agency.

NASA is reluctant to discuss the ultimate future of Starliner, but said only after these assessments, will NASA determine whether the spacecraft will conduct a second, uncrewed flight test into orbit before astronauts fly on board.

"Given the potential for systemic issues at Boeing, I would also note that NASA has decided to proceed with an organisational safety assessment with Boeing as they previously conducted with SpaceX," says chair of the safety panel, Patricia Sanders.