The most powerful explosion ever seen in the Universe since the Big Bang has been spotted by astronomers studying a supermassive black hole at the centre of a galaxy hundreds of millions of light-years away.

The huge eruption, which released five times more energy than the previous record holder – MS 0735.6+7421 – occurred in the Ophiuchus galaxy cluster; a colossal cosmic collection of thousands of individual galaxies stationed some 390 million light-years from Earth.

The outburst is thought to result from the feeding habits of the supermassive black hole that sits at the core of the cluster’s central galaxy.

As the behemoth object actively munches on the surrounding gas, it released large amounts of matter and energy as powerful jets that astronomers were able to observe with ESA’s XMM-Newton and NASA’s Chandra X-ray space observatories. The record-breaking, gargantuan eruption was also picked up in radio data from the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) in Australia and the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) in India.

"We've seen outbursts in the centres of galaxies before but this one is really, really massive," says Professor Melanie Johnston-Hollitt at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy in Australia who is a co-author on the research paper detailing the discovery.

"And we don't know why it's so big. But it happened very slowly – like an explosion in slow motion that took place over hundreds of millions of years,” she said.

The first hint that a giant explosion had occurred was reported in 2016 when another team of astronomers studying a Chandra image of Ophiuchus spotted an unusual curved edge in the cluster.

Initially, the team considered whether this edge might point to a hole in the hot gas that had been punched through by the black hole jets, but the possibility was discarded at the time.

However, when lead author of the current study, Simona Giacintucci of the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC and colleagues investigated further, they saw that the cavity was filled with radio emission from electrons accelerated to almost the speed of light.

When placed together, the two pieces of evidence added up to one monstrous blast.

"The radio data fit inside the X-rays like a hand in a glove," said co-author Maxim Markevitch of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "This is the clincher that tells us an eruption of unprecedented size occurred here."

This unrivalled event is like the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, which ripped the top off the mountain, says lead author of the study Dr Simona Giacintucci, from the Naval Research Laboratory in the United States.

"The difference is that you could fit 15 Milky Way galaxies in a row into the crater this eruption punched into the cluster's hot gas," she said.

The finding highlights the difference that multiwavelength observations can make in understanding the various physical processes at work in the Universe; processes that should become more transparent when projects such as the huge continent-spanning Square Kilometre Array (SKA) and others like it reach their full potential.

"We made this discovery with Phase 1 of the MWA, when the telescope had 2048 antennas pointed towards the sky," Johnston-Hollitt said.

"We're soon going to be gathering observations with 4096 antennas, which should be ten times more sensitive. I think that's pretty exciting."

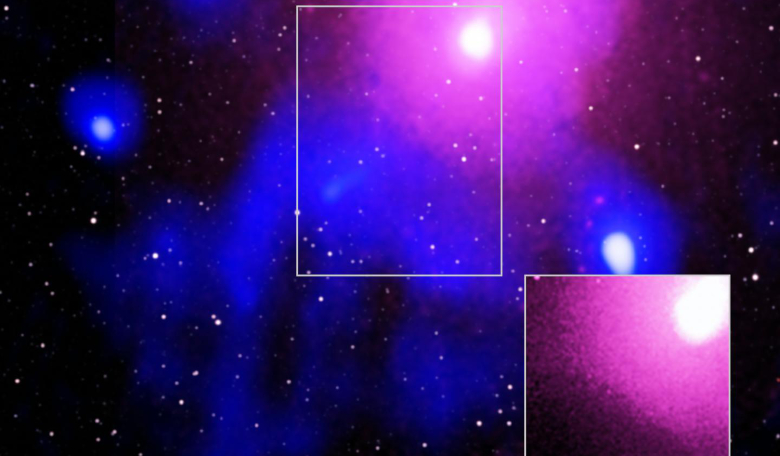

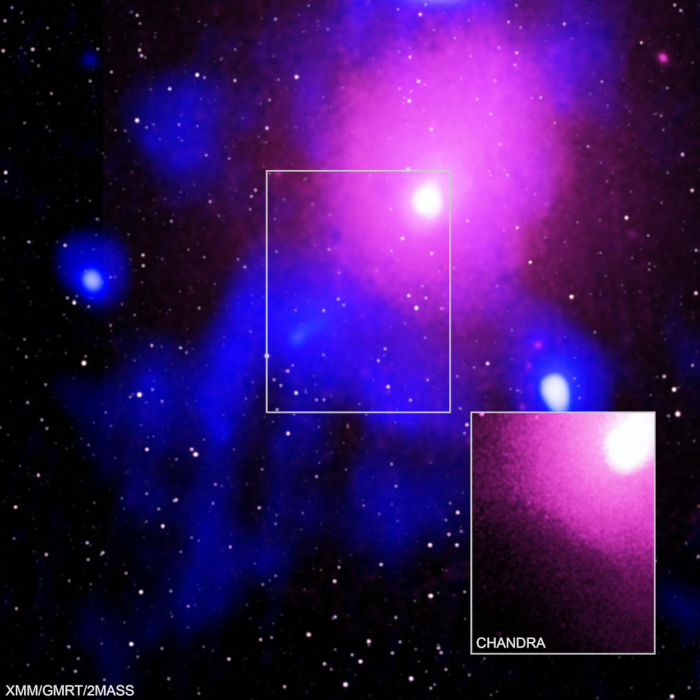

In this image, the diffuse hot gas pervading the cluster is revealed through X-ray observations from XMM-Newton (shown in pink), radio data from the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (shown in blue), and infrared data from the 2MASS survey (shown in white). The inset in the lower right shows a zoomed-in X-ray view based on Chandra data (also shown in pink), while bright dots sprinkled across the image reflect the distribution of foreground stars and galaxies. Image:X-ray: NASA/CXC/Naval Research Lab/Giacintucci, S.; XMM:ESA/XMM; Radio: NCRA/TIFR/GMRTN; Infrared: 2MASS/UMass/IPAC-Caltech/NASA/NSF