Astronomers have discovered 12 smaller black holes orbiting the supermassive black hole in the centre of our galaxy, and their existence suggests that there could be up to 10,000 more within just three light years of the Galactic Centre.

The discovery, made by a team from Columbia University, helps support a long standing theory that thousands of black holes surround supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at the centre of large galaxies, but with black holes being what they are, it is a theory that up until now has been difficult to prove.

"There are only about five dozen known black holes in the entire galaxy – 100,000 light years wide – and there are supposed to be 10,000 to 20,000 of these things in a region just six light years wide that no one has been able to find," said Chuck Hailey, co-director of the Columbia Astrophysics Lab and lead author on the study.

The Milky Way is really the only galaxy astronomers have where the interaction of supermassive black holes with smaller ones can be studied, because researchers struggle to see the interplay between the two in other galaxies.

Extensive, but fruitless searches have been made in the past for black holes surrounding Sgr A*, the closest supermassive black hole (SMBH) to Earth and therefore the easiest to study, but so far, “there hasn't been much credible evidence,” added Hailey.

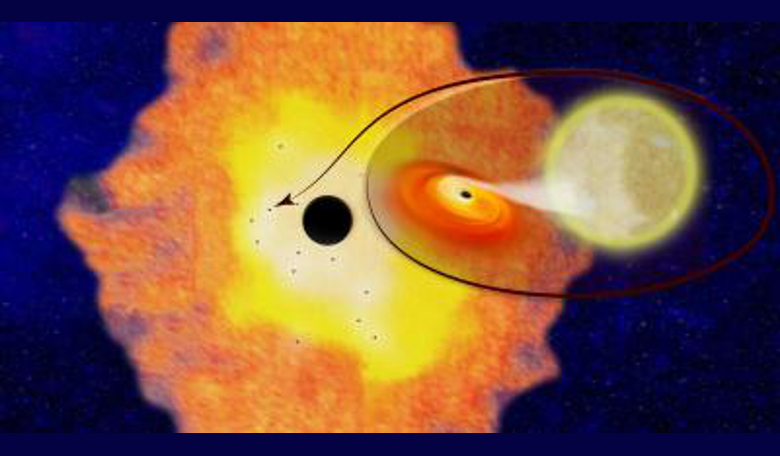

It has long been theorised that many smaller black holes should exist in the vicinity of SMBHs because conditions surrounding these behemoths are the perfect breeding ground for the birth of massive stars. As the fate of massive stars is generally to form black holes after their relatively brief lifespans, it stands to reason that there should be a lot more black holes than can be seen.

It is also thought that any black holes formed outside of the halo which are starting to lose their energy, can be pulled into the SMBH’s neighbourhood where they are held captive by its force, therefore adding to the glut of black holes already in the ‘local’ area.

Despite their apparent numbers, finding them is still difficult and astronomers have been searching for bright bursts of X-ray that sometimes occur when black holes capture and attach themselves to a passing star, forming a stellar binary.

"It's an obvious way to want to look for black holes," Hailey said, "but the Galactic Center is so far away from Earth that those bursts are only strong and bright enough to see about once every 100 to 1,000 years." Instead Hailey and his colleagues looked for the fainter, but steadier X-rays emitted when the binaries are in an inactive state.

Using archival data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory to test their technique, Hailey and colleagues searched for X-ray signatures of black hole-low mass binaries and were able to find a dozen within three light years, of Sgr A*.

By extrapolating what fraction of black holes will join with low mass stars, the team could infer the population of isolated black holes out in the galaxy and the figures are quite substantial; anywhere from 300 to 500 black hole-low mass binaries and about 10,000 isolated black holes are expected to exist in the area surrounding Sgr A*.

"This finding confirms a major theory and the implications are many," Hailey said. "It is going to significantly advance gravitational wave research because knowing the number of black holes in the centre of a typical galaxy can help in better predicting how many gravitational wave events may be associated with them. All the information astrophysicists need is at the centre of the galaxy."