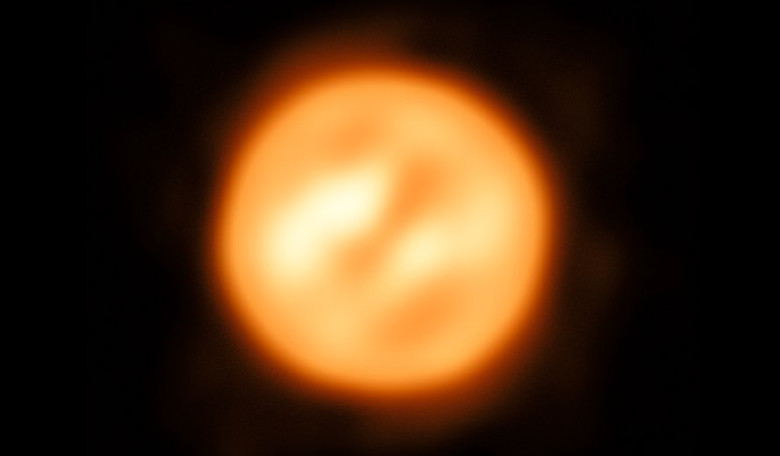

The most detailed image ever of a star other than our Sun has been constructed by astronomers using ESO’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI).

The star is the red supergiant Antares – the brightest star in the heart of the constellation of Scorpius. Red supergiants may be the largest stars in the Universe by volume, but they are not the most massive or luminous. In fact Antares is tinged red because it is relatively cool, despite being so huge.

Antares is now thought to have a mass around 12 times that of the Sun with a diameter about 700 times larger than the Sun, due to significant mass loss (around three solar masses worth), that it has shed over its lifetime.

Like all red supergiants, these huge dying stars are nearing the end of their lives, and indeed Antares is expected to explode as a supernova, possibly within the next few hundred thousand years. Now however, the bloated outer layers of the star’s atmosphere mean that if the star were placed in the centre of the Solar System its outer surface would lie between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

Understanding how these huge dying stars lose mass so quickly in the final phase of their evolution, has been a long-standing problem in astronomy. Consequently, a team of astronomers, led by Keiichi Ohnaka, of the Universidad Católica del Norte in Chile has now used ESO’s VLTI at the Paranal Observatory in Chile to map Antares’s surface and to measure the velocities of material in its atmosphere.

“The VLTI is the only facility that can directly measure the gas motions in the extended atmosphere of Antares — a crucial step towards clarifying this problem. The next challenge is to identify what’s driving the turbulent motions,” said Ohnaka, who is also the lead author of the research paper recently submitted to Nature.

With the new data obtained from the VLTI, the team calculated the difference between the speed of the atmospheric gas at different positions on the star and the average speed over the entire star, to produce the first two-dimensional velocity map of the atmosphere of a star other than the sun.

It was found that turbulent, low-density gas was located much further from the star than predicted - a result that was not consistent with movement from convection. Convection is the transfer of heat from one place to another by the movement of fluids, such as liquids, gases and plasma. In the case of Antares it is taken to mean the large-scale movement of matter which transfers energy from the core to its outer atmosphere.

So how did the gas get to where it was without convection? The team are unsure but they suggest that a new, currently unknown process may be needed to explain these movements in the extended atmospheres of red supergiants like Antares.

“In the future, this observing technique can be applied to different types of stars to study their surfaces and atmospheres in unprecedented detail. This has been limited to just the Sun up to now,” concludes Ohnaka. “Our work brings stellar astrophysics to a new dimension and opens an entirely new window to observe stars.”