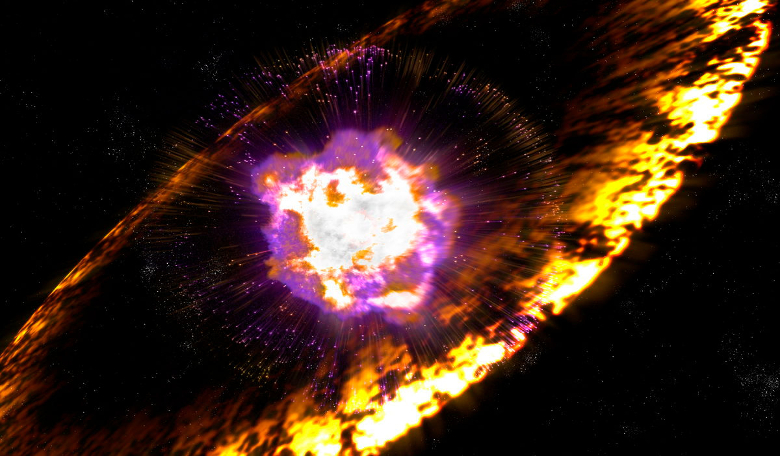

Did two prehistoric supernovae exploding about 300 light years from Earth cause mutations to plant and animal life as little as 2 million years ago? Scientists from the University of Kansas studying the effects of such an explosion, think perhaps so. Using computer modelling to ascertain the affects of two stars that went supernova approximately 1.7 to 3.2 million and 6.5 to 8.7 million years ago, Adrian Melott, professor of physics at the University of Kansas, suggests that along with disrupting animals' sleep patterns for a few weeks due to the incredibly light nights that would have occurred as a result of the explosions, cosmic rays may have caused mutations to life on Earth on a cellular level.

"I was surprised to see as much effect as there was," said Melott. "I was expecting there to be very little effect at all," he said. "The supernovae were pretty far way – more than 300 light years – that's really not very close. The big thing turns out to be the cosmic rays. The really high-energy ones are pretty rare… [these] are the ones that can penetrate the atmosphere. They tear up molecules, they can rip electrons off atoms, and that goes on right down to the ground level. Normally that happens only at high altitude."

The research suggests that the supernovae might have caused a 20-fold increase in irradiation by muons – an unstable subatomic particle of the same class as an electron – at ground level on Earth. This boosted exposure to cosmic rays would be equivalent to one CT scan per year for every creature inhabiting land or shallower parts of the ocean.

Muons make up much of the cosmic radiation reaching the earth's surface and usually they just pass straight through us, but with a mass around 200 times greater than an electron, they can penetrate hundreds of meters of rock. "Normally there are lots of them hitting us on the ground, but because of their large numbers they contribute about 1/6 of our normal radiation dose. So if there were 20 times as many, you're in the ballpark of tripling the radiation dose." Would this increased radiation be high enough to boost the mutation rate and frequency of cancer? “Not enormously. Still, if you increased the mutation rate you might speed up evolution,” explained Merlot.

It is perhaps coincidental, but around 2.59 million years ago a minor mass extinction occurred. This may be connected to a cooling in Earths climate, as the increased abundance of cosmic rays ionised Earth’s troposphere – the lowest level of the atmosphere – to a level eight times higher than normal and subsequently causing an increase in cloud-to-ground lightning.

"There was climate change around this time," said Melott. "Africa dried out, and a lot of the forest turned into savannah. Around this time and afterwards, we started having glaciations – ice ages – over and over again, and it's not clear why that started to happen. It's controversial, but maybe cosmic rays had something to do with it."