An unseen source of X-rays which appeared to blast out from one of the brightest supernovas ever recorded could have marked the birth of a black hole or neutron star say astronomers. If correct, this would be the first time such an event has been seen.

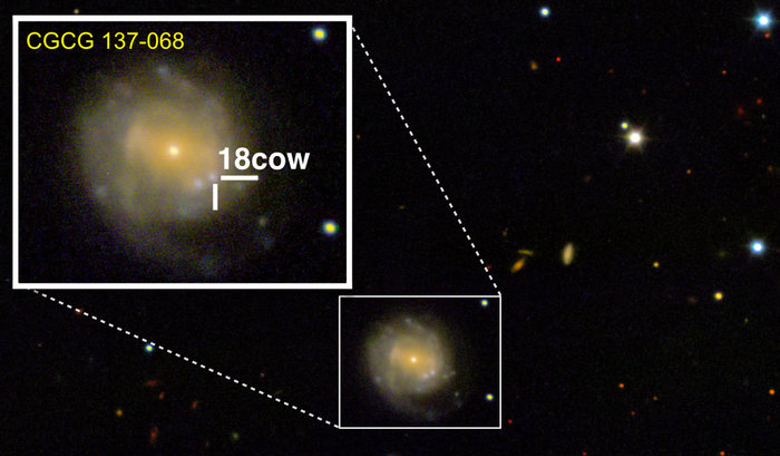

The supernova at the centre of the phenomena was first spotted by the ATLAS telescope in Hawaii, but it was soon apparent that this was no ordinary death throe of an ageing massive star. The objects unusual behaviour sparked a frenzy of activity from astronomers across the world who were quick to point a swarth of space- and ground-based telescopes including ESA’s Integral and XMM-Newton and NASA’s NuSTAR and Swift space telescopes at a galaxy some 200 million light years away, where the object suddenly appeared in the sky earlier this year.

Observed to be 10 to 100 times brighter than any other supernova previously detected, it also reached peak luminosity in only a few days compared to the usual two weeks associated with standard stellar explosions.

Although most of a supernova’s energy is blown out from its core in the form of neutrinos, they also bathe their surroundings in a gamut of radiation across the whole electromagnetic spectrum, as this almighty explosion ensues.

Most notable is the emittance of high-energy X-rays that gradually fade as the stellar explosion loses energy. However AT2018cow, as the object has become known, had other redeeming features that marked it out as being different from the rest.

Not only were low-energy X-Rays still visible from within AT2018cow, but the data also indicated that the object was drawing material back in.

“This is the most unusual thing that we have observed in AT2018cow and it’s definitely something unprecedented in the world of explosive transient astronomical events,” says Raffaella Margutti of Northwestern University, USA, lead author of the paper.

These strange phenomena therefore more than likely herald the creation of something never seen before. “We know that black holes and neutron stars form when stars collapse and explode as a supernova, but never before have we seen one right at the time of birth,” adds co-author Indrek Vurm of Tartu Observatory, Estonia, who worked on modelling the observations.

If this is indeed what is proposed, then astronomers should be able to confirm with continued observations of AT2018cow as accreting black holes leave characteristic imprints in X-rays, which might be able to be detected in any subsequent data that is collected.

“This event was completely unexpected and it shows that there is a lot of which we don’t completely understand,” says Norbert Schartel, ESA’s XMM-Newton project scientist. “One satellite, one instrument alone, would never be able to understand such a complex object. The detailed insights we were able to gather into the inner workings of the mysterious AT2018cow explosion were only achievable thanks to the broad cooperation and combination of many telescopes.”