Four weeks after the hugely exciting news that a gas associated with signs of life (PH3) had been spotted in the cloud tops of Venus, ESA’s BepiColombo mission might be able to add to this discovery as it makes its first flyby of Venus on its seven year journey to the innermost planet, Mercury.

In September, a team led by Jane Greaves at Cardiff University detected the spectral signature of phosphine (PH3), a phosphorus-hydrogen compound that on Earth can only be made via industrial processes or via microbes that do not need oxygen to survive.

Its discovery made headlines around the world and for a good reason; if PH3 is being produced by biological means, it will be the first detection of life on another planet.

However, while phosphine is a strong indicator of biological activity, it is hard to tell definitively without further detections. Even Greaves and colleagues hastily pointed out that PH3 “is not robust evidence for life, only for anomalous and unexplained chemistry.”

Nonetheless, the detection spurred on global private and governmental efforts to push ahead with missions that could provide irrefutable evidence for or against signs of life.

Quite by chance, that evidence, or at least further opportunities to study Venus from a much closer perspective, will happen next week.

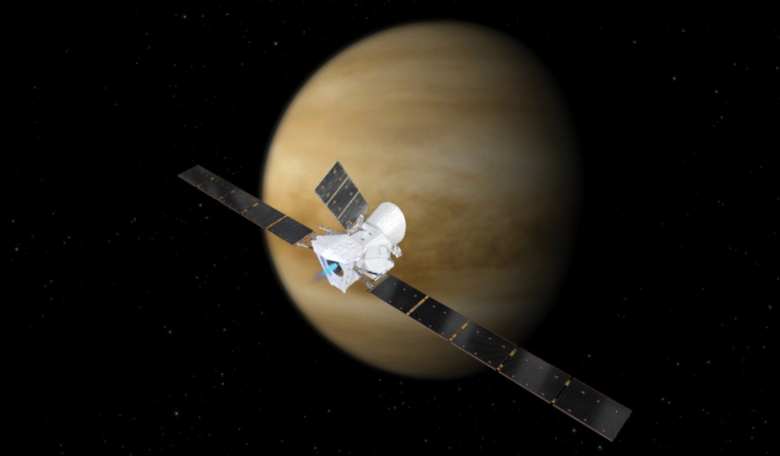

Launched nearly two years ago, the Mercury probe BepiColombo, a joint endeavour between ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA, will get within 10 720 kilometres of Venus on its way to explore the smallest terrestrial planet in the Solar System.

BepiColombo consists of two scientific orbiters: the European Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and Japan's Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO).

Even though the spacecraft will be quite far away from Venus during the first flyby, the BepiColombo teams were already planning to operate eight out of eleven science instruments on the MPO and three out of five on the MMO to examine the planet’s atmosphere and space environment.

Now, following the detection of phosphine from telescopes on Earth, the team want to see if one of those instruments – MERTIS (Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Imaging Spectrometer) – is capable of hunting for PH3.

“We possibly could detect phosphine,” ESA's Johannes Benkhoff, BepiColombo's Project Scientist said in an interview with Forbes. “But we do not know if our instrument is sensitive enough.”

It is probably too late in the day for the BepiColombo team to realistically search for phosphine, as the mission objectives for this flyby are already set, but a second flyby scheduled for next year that will get as close as 550 kilometers from Venus could hold out more hope.

“[On the first flyby] we have to get very, very lucky. On the second one, we only have to get very lucky. But it’s really at the limit of what we can do,” says Jörn Helbert from the German Aerospace Center, co-lead on the MERTIS instrument.

The prospect of BepiColombo independently corroborating the detection made by Greaves and colleagues is tantalising, but if it turns out the Mercury probe is not suited to search for PH3, others such as Rocket Lab’s intended Venus mission and future Venera missions planned by Russia, might get lucky instead.

Although the detection of phosphine is not expected, the Planetary Virtual Observatory and Laboratory (PVOL) is asking for amateurs equipped for UV or IR imaging to contribute observations to enhance the scientific return of next weeks flyby.

“We are seeking context observations of Venus provided by amateur astronomers to enhance the scientific return of the BepiColombo flyby in October 15, 2020,” the PVOL website says.

Highlights of these amateur observations will be posted on the PVOL webpage and on the BepiColombo ESA page dedicated to the flyby.