After two decades of collecting micrometeorite material at a remote outpost in Antarctica, scientists have determined that as much as 5,200 tons of interplanetary dust particles rain down on our planet every year – most of which comes from comets orbiting Jupiter.

Located 1,100 kilometres off the coast of Adelie Land, in the heart of Antarctica, is the Franco-Italian Concordia station (Dome C), which sits at 3,233 m (10,607 ft) above sea level.

Jointly operated all year round by scientists from France and Italy, this facility is perfectly suited to studying the influx of material bombarding our planet year in year out, as snow from central Antarctica offers a unique advantage for cosmic dust collection.

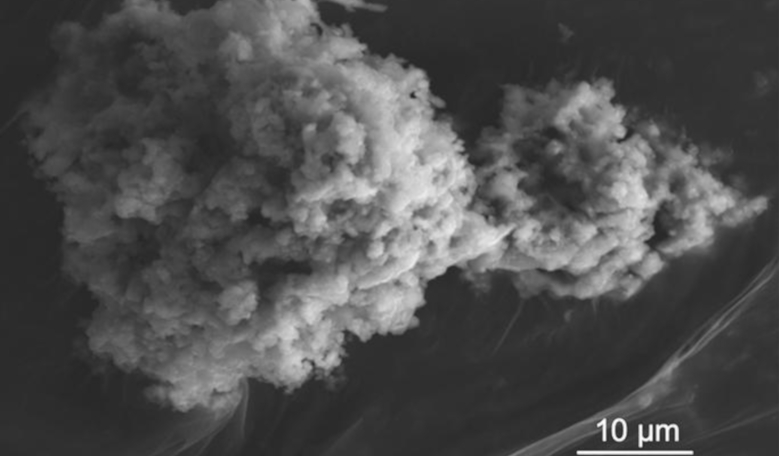

Trapped in this ultra-clean snow are tiny extraterrestrial dust particles and cosmic spherules no bigger than a fraction of a millimetre, which have found their way to Earth’s surface from a passing comet or asteroid.

Particles such as these have been found on Earth for over a century and were first discovered in deep-sea sediments collected by ships such as the HMS Challenger in the 1870s. But even after all of these years many uncertainties still remain due to the difficulties in collecting and analysing such delicate particles.

Now after sifting through snow gathered from the vicinity of the Concordia Station over a twenty year period, an international team of scientists from the CNRS (Centre national de la recherche scientifique), the Universite Paris-Saclay and the National Museum of Natural History with the support of the French polar institute, have the answer. And its a lot.

Heading up six expeditions in the snowy wilderness is CNRS researcher Jean Duprat and a dedicated team of scientists who have collected enough extraterrestrial particles to measure their annual flux, which corresponds to the mass accreted on Earth per square metre per year.

The particles range from 30 to 200 micrometres in size and were distinguished from their earthly counterparts by their composition.

A total of 1280 unmelted micrometeorites (uMMs) and 808 cosmic spherules (CSs) with diameters ranging from 30 to 350 μm (micrometre) were identified, say the team and from this they were able to use numerical simulations to extrapolate results to apply on a world-wide basis.

When calculated on a global scale extraterrestrial dust amounts to round 5,200 tons of particles in the 12-700 μm diameter range, say the team.

This is significantly more than the influx from larger pieces that are chipped off when meteorites plummeting through our skies, which accounts for less than ten tons per year.

But that is nothing to compared to the total amount of dust mass which could be floating about above our skies before it passes through the atmosphere.

From their models, the team estimate that as much as 15,000 tons per year could actually be swamping Earth on a yearly basis.

Although this estimated figure is significantly different from the actual extrapolated data, there are a number of reasons for this say the team, including dust evading detection or that it is being removed prior to atmospheric entry.

From their models, the team were also able to infer the source of all of this dust. Based on the density of the grains, whereby a higher density and lower porosity suggest a meteoritic origin and a lower density and higher porosity suggest a cometary origin, the team suggest that around 80 percent of the incoming extraterrestrial flux originates from Jupiter family comets and the rest from asteroids.

Understanding the role played by these interplanetary dust particles is invaluable say the team as it could provide information on how water and carbonaceous molecules were supplied to a young Earth.

This study will be available in Earth and Planetary Science Letters from 15 April, 2021.