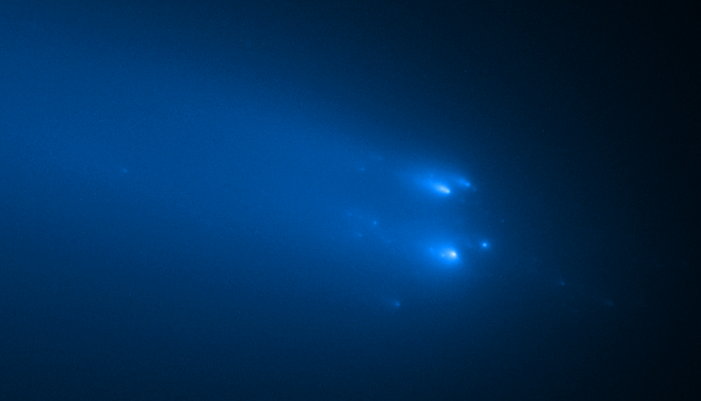

Hopes of observing what could have been one of the brightest comets to fly past Earth in years were dashed last month, when reports that Comet C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) had started fading in brightness and was potentially breaking apart. This was confirmed by images from Hubble which showed the football field-sized icy object breaking into chunks the size of a small house.

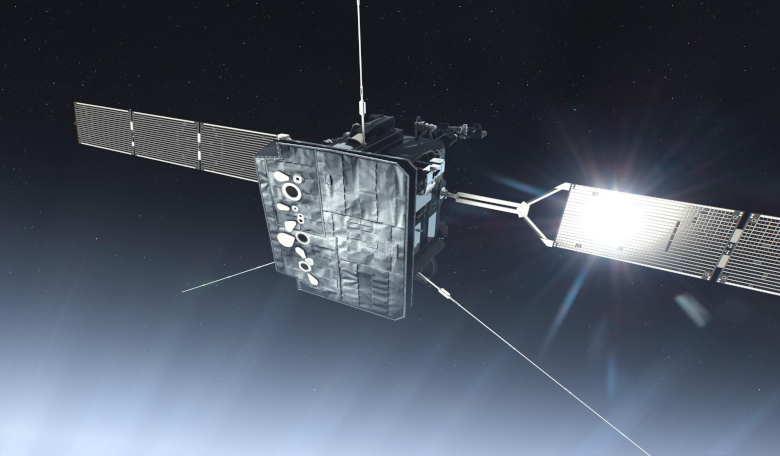

But in a new twist of events, it turns out it might not all be bad news, as ESA’s sun-observing satellite Solar Orbiter, could be in the right place at the right time to encounter the comet's ion and dust tail end of May/beginning of June.

Comet ATLAS was discovered on 28 December, 2019, by the system that gives it its name; the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) - a robotic astronomical survey stationed atop Mauna Loa in Hawaii.

With a 4000-fold increase in brightness between the beginning of February and near the end of March, the increase in activity of the Comet as it approached the Sun was expected to make it visible to the naked eye; a boon for comet watchers everywhere.

However, the anticipated spectacle was short-lived as by April, another monitoring programme, this time carried out by the 0.6-m Ningbo Education Xinjiang Telescope (NEXT), caught images of the possible disintegration of the comet. An event later confirmed by Hubble.

Although the comet has since undergone a resurgence in brightness following its demise, it is unlikely to stay bright for long, but handily astronomers might be able to learn more about comet ATLAS than originally planned thanks to a spacecraft on a mission to study the Sun and its inner heliosphere; The European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter spacecraft.

Launched on 10 February, 2020, the observatory is now on a two year cruise towards the innermost regions of the Solar System and is using Venus and Earth to slingshot itself into the correct trajectory.

But by a happy coincidence, the Orbiters path to the Sun will now place it downstream of the comet in the solar wind in a position that will potentially allow the craft to perform an in-situ detection of the comet's ion and/or dust tails, with the first encounter just over two weeks from now.

“The spacecraft may encounter the comet's ion tail around 2020 May 31—June 1, and that the comet's dust tail may be crossed on 2020 June 6,” write a trio of scientists, Geraint Jones, Qasim Afghan and Oliver Price, at Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London, who have calculated the positions of both the craft and comet.

Packed on board Solar Orbiter is a Solar Wind Plasma Analyzer (SWA). This instrument will be able to detect ionised atoms and molecules in the gas surrounding the comet as it gets bombarded by charged particles streaming off the Sun.

But, as timely as this stroke of luck is, there will only be something to see if the comet is losing enough material at the time say Jones and colleagues.

Failing that, a week later the Orbiter will have the chance to detect minute particles in the comet’s dust tail if they happen to bump into the spacecraft’s Radio and Plasma Waves experiment; an instrument that was initially intended to determine the characteristics of electromagnetic and electrostatic waves in the solar wind via both in situ and remote-sensing measurements.

Uncommon events known as Interplanetary Field Enhancements, IFEs, are another solar wind phenomenon that may be observed around the time of the orbital plane crossing note the authors in their paper published in the journal Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society.

All eyes will now be on Solar Orbiter and if the spacecraft’s instruments do detect material from Comet ATLAS, “it will be the first predicted serendipitous comet tail crossing by an active spacecraft carrying appropriate instrumentation for the detection of cometary material,” say the trio.

Comet ATLAS will reach its nearest point to Earth on 23 May and come to perihelion (closest to the Sun) on 31 May, 2020.

Hubble Space Telescope image of comet C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) on April 20, 2020. Image via NASA/ ESA/ STScI/ D. Jewitt (UCLA)

If you've enjoyed reading this article, please consider subscribing to ROOM Space Journal to gain immediate and full access to the latest magazine feature articles and receive your own print and/or digital copies of ROOM magazine delivered direct to your door or electronically.