Although the news about a possible ninth planet might have slowed down, the quest to find it has not. Using data gathered from Cassini’s flybys of Saturn, Jupiter and the outer planets to track the positions and velocities of solar system bodies, researchers have constructed models to constrain a possible location of Planet Nine.

The hunt for a Planet X started in 1915 and with the discovery of objects such as Sedna, a dwarf planet as big as Pluto and more recently another Kuiper Belt object known as (KBO) 2012 VP113 detected in the inner Oort cloud in 2014, the question of whether a massive planet really does reside in the outer solar system has been revived. Earlier this year, two Caltech researchers provided the most compelling evidence yet that Planet X or Planet 9 as it has been nicknamed, resides in a highly elongated orbit that would take between 10,000 and 20,000 years to make just one full orbit around the sun.

Planet 9 is calculated to have a mass about 10 times that of Earth and its theoretical discovery was made through mathematical modelling and computer simulations of a cluster of six other objects in the Kuiper Belt, whose orbits showed apparent unconnected alignments. It was then found by Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown that if they included a massive planet in an anti-aligned orbit in their simulations, their models predicted the alignment that is actually observed by the smaller objects. A predicted consequence of Planet Nine is that a second set of confined objects should also exist. These objects are forced into positions at right angles to Planet 9 and into orbits that are perpendicular to the plane of the solar system and indeed, five known objects that have already been discovered fit this prediction precisely.

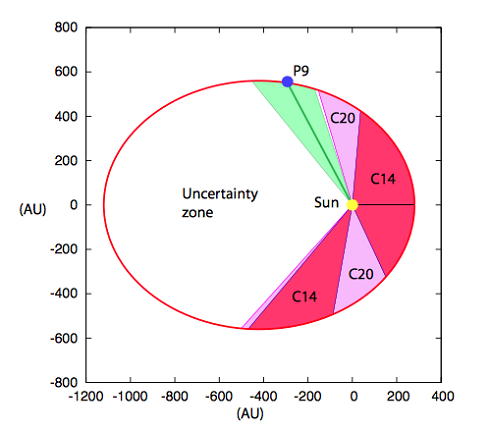

Allowed zone for Planet 9 (P9). The red zone (C14) is excluded by the analysis of the Cassini data up to 2014. The pink zone (C20) is how much this zone can be enlarged by extending the Cassini data to 2020.

Allowed zone for Planet 9 (P9). The red zone (C14) is excluded by the analysis of the Cassini data up to 2014. The pink zone (C20) is how much this zone can be enlarged by extending the Cassini data to 2020.

Now, using a database, known as INPOP, that tracks the orbits and velocities of planets and smaller objects such as the Moon, a team of researchers based in France have modelled how Planet 9 might affect the orbits of the main planets of our solar system, not just Kuiper Belt objects to help constrain the most probable location of Planet 9. Their derived location, shown in green in the included diagram, contradicts recent work completed by another researcher, who after studying the perturbing effects that a hypothesised distant planet would have on the orbital motion of Saturn, concluded that such a planet (with a mass ten times greater than Earth) is excluded from models if it resides closer to 1000 AU of the Sun.

INPOP is one of a handful of databases used by researchers to study the calculated positions of a celestial object at regular intervals throughout a period, known as an ephemeris. INPOP has been regularly updated with data obtained by Cassini in its recent flybys of the giant gas planets and is noted by the research team to be the most precise sensor for testing the possibility of an additional body in the solar system. INPOP planetary ephemerides are also regularly produced and used for studying variations in the solar plasma density, estimating asteroid masses and testing alternative theories of gravity.

The existence of a massive object in the outer solar system is important for studying the present solar system’s architecture such as the mass distribution of the material beyond the limit of 50 astronomical units (AU) and the spatial distribution of objects between 40 to 50 AU, but its discovery will also give important clues on why the solar system looks like it does today. Not only that, but as there have only been two true planets discovered since ancient times, finding something as significant as Planet 9 would surely ensure a place in

Additional information on this research can be found here: www.arxiv.org