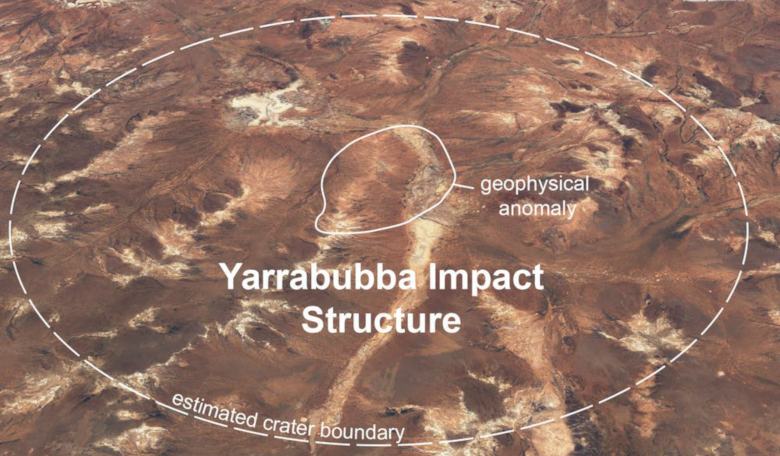

A barely-there shallow depression stretching 70 kilometres in diameter in the outback of Australia has just been confirmed as the oldest preserved crater on the planet and with an age of 2.29 billion years, it might have also helped end a long-term ice age.

Yarrabubba crater in Western Australia has long been regarded as one of the most ancient impact structures on Earth. However, until now scientists have lacked the evidence to precisely date this meteorite strike which is thought to have hit when our planet was just half the age it is now.

Finding evidence of these ancient collisions is difficult. Earth is very active and it’s land is constantly resurfaced through plate tectonics and volcanoes, amongst other things. Craters older that Yarrabubba most likely exist and indeed rocks within the Kaapvaal craton of southern Africa and the Pilbara Craton in Western Australia indicate these could be impacts which occurred around 3470 to 2460 million years ago. Unfortunately any telltale signs that mark out a meteorite strike, however worn away they might be, have not been found to authenticate their status.

Yarrabubba is no exception. No circular crater remains at the site, but a 20 kilometre diameter magnetic anomaly is present and scientists believe this marks what would have been the familiar central section of the crater which lifts up after impact.

“The landscape is barren, but not empty. Bits of rocks exposed near the centre of the formerly giant crater hold the microscopic clues to the past violence that occurred 2.229 billion years ago,” says Timmons Erickson at NASA Johnson Space Centre, Houston, US, lead author of a study published in Nature Communications.

Contained within those chunks of rock where tiny zircon and monazite crystals that left a "shocked" imprint in them when the meteorite struck Earth.

Monazite is a reddish-brown phosphate mineral containing rare-earth metals, one of which is uranium.

As uranium breaks down, it releases helium at a consistent pace, and researchers were able to calculate how much time had passed as the radioactive element decayed.

“When a giant impact forms, rocks in the centre get hot enough to cause the atomic bonds in the mineral to break open and reform. This process evacuates the accumulated lead. After the impact, lead starts collecting again,” says co-author Aaron Cavosie from Curtin University, Western Australia.

Aside from pushing back the date of the oldest known meteorite impact, which until now was believed to be Vredefort Dome in South Africa - now dated as forming 2000 years after Yarrabubba – this breakthrough finding might also have consequences for another significant period in our planet’s history - the end of Snowball Earth.

"[The] crater was made right at the end of what's commonly referred to as the early Snowball Earth, a time when the atmosphere and oceans were evolving and becoming more oxygenated and when rocks deposited on many continents recorded glacial conditions," says Professor Christopher Kirkland also at Curtin University.

The Snowball Earth hypothesis proposes that sometime before 650 million years ago, Earth’s surface became entirely or nearly entirely frozen. At some point, the icy crust melted and the planet began to rapidly warm.

It just so happens that the age of the crater corresponds closely with the end of a potential global glacial period, Prof Kirkland said and its possible the impact may have triggered a change in global climate.

To test the theory, Erickson and colleagues ran a number of numerical simulations to explore the potential effects that a Yarrabubba-sized impact may have had on climactic conditions.

If the meteorite hit Earth when it was covered by an ice sheet between 2 to 5 kilometres thick, up to half a trillion tonnes of water vapour, a greenhouse gas, could have been released into the atmosphere from the melting ice within moments of the impact.

This in turn could have helped the planet warm up during the Proterozoic era - a period when complex life had not yet formed and relatively little oxygen filled the skies.

Its hard to say for sure, but the effects of impact cratering have long been recognised as drivers of climate change over Earth’s history; the Chicxulub crater in Mexico is another example which is believed to have resulted in global cooling of oceans and production of widespread acidic rains.

"Obviously we were very excited just with the age itself," Prof Kirkland said. "But placing that right with the context of Earth's other events makes it become really very interesting."