In this NewSpace age, public and private interests are both cooperating and competing to build permanent outposts on the Moon, mine planets and asteroids, and colonise Mars, all supposedly with the best of possible intentions - the salvation of humanity through the exploitation of space. Philosopher of science and religion Mary-Jane Rubenstein irreverently describes the outer space of today as a place of utopian dreams, salvation dramas, saviour complexes, apocalyptic imaginings, gods, goddesses, heroes and villains. In this extract from her book, Astrotopia: The Dangerous Religion of the Corporate Space Race, she considers the currently ‘on-trend’ goal of terraforming and colonising Mars. Could it be done, should it be done and would it actually ‘save’ anyone?

Mars! Not the most hospitable planet in the galaxy (that would be Earth.) First of all, Mars is freezing: the average temperature is around -80 degrees Fahrenheit (-62C), a little colder than Antarctica. In the summertime, some places can reach 70F (21C), but in the winter, temperatures at the poles can drop to -220F (-140C), which is significantly colder than anything humans have recorded on Earth. And the temperature is just the beginning.

The atmosphere on Mars is 95 percent carbon dioxide, so we couldn’t breathe there. The atmospheric pressure is too low to support any sort of life we’ve learned about on Earth. The soil is superfine, toxic to plants and animals, and prone to forming ‘dust devils’ that whirl across the surface at 30 to 60 miles per hour, leaving an atmospheric haze in their wake for days or even weeks. And to top it all off, there’s no magnetosphere, so the Red Planet is constantly bombarded by carcinogenic solar and galactic radiation.

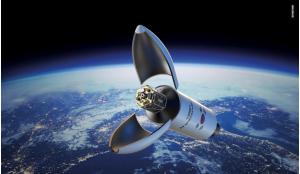

The second test flight of SpaceX’s Starship took place on 18 October 2023. The system’s software was triggered to terminate the flight, exploding the spacecraft around eight minutes after take-off when contact with it was lost.

The second test flight of SpaceX’s Starship took place on 18 October 2023. The system’s software was triggered to terminate the flight, exploding the spacecraft around eight minutes after take-off when contact with it was lost.

Fixer-upper

Why not put all that money, energy, and manly frontierism into bringing our own ecosystem back to life?

For anyone who’s wondering how bad Mars could actually be, science writer Ross Andersen explains, “if you were to stroll onto its surface without a spacesuit, your eyes and skin would peel away like sheets of burning paper, and your blood would turn to steam, killing you within 30 seconds”. (Viewers of the US TV show, Saturday Night Live, might recall the stomach-churning scene from the episode Elon Musk hosted in May 2021, when Pete Davidson’s monosyllabic character, Chad, tries to remove his helmet and his face explodes). “Even in a suit,” Andersen continues, “you’d be vulnerable to cosmic radiation, and dust storms that occasionally coat the entire Martian globe in clouds of skin-burning particulates, small enough to penetrate the tightest of seams.” In short, as SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell admits, Mars is a bit of a “fixer-upper of a planet”.

Okay, but how do you fix up a planet? Isn’t this already the question on everyone’s mind when it comes to our poisoned Earth? How do you scrub the carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, the acid out of the rain, the plastic out of the oceans, the infestations out of the trees, those few degrees out of the climate?

Well, it turns out that the same processes currently destroying life on Earth might actually create it on Mars. At least, that’s what the Red Planetarians tell us. Robert Zubrin, President of the Mars Society, says that the trick to making Mars habitable would be “intentionally manufacturing a greenhouse effect” akin to the one we’ve created here. It would just be a matter of “producing fluorocarbon super-greenhouse gases on Mars… and wilfully dumping these climate-altering substances into the atmosphere”.

Artist’s concept depicting the first astronauts and human habitats on Mars.

Artist’s concept depicting the first astronauts and human habitats on Mars.

What could possibly go wrong?

VaughanSpaceX“If there is life on Mars, I believe we should do nothing with Mars. Mars then belongs to the Martians, even if the Martians are only microbes.” Carl Sagan

Zubrin’s plan is one instance of a process called terraforming: the hypothetical recreation of a planet in the image of Earth. At first, humans on Mars would need to live in underground bunkers, grow food in inflatable greenhouses, figure out how to manufacture things in 37 percent gravity, and send rovers to find water and metal deposits. Once they’d harvested enough in situ materials and learned how to make bricks, plastics, glasses, metals and ceramics, the Martian pioneers could build pressurised structures above ground and move into “domains the size of shopping malls”. In the meantime, they’d be working to raise the planet’s temperature to a balmy 32F (0C), probably about as much as you can ask of this fourth planet from the Sun.

Proposals for warming up Mars vary dramatically. Some people join Zubrin in suggesting that tons of chlorofluorocarbons unleashed throughout the globe might just do the trick. Others focus on the frozen ice caps, which contain both water and carbon dioxide. We could melt the caps with orbital mirrors, or paint them with black soot, or cover them with lichens, or blast them with solar-powered space lasers… or, if Musk has his way, ‘nuke’ them with ten thousand missiles. Either way, planetary scientist Christopher McKay estimates it would take about 100 years to make the planet as warm as an ordinary springtime in Alaska.

But that’s just the temperature. Air is another matter entirely. Creating a breathable atmosphere on Mars would require far more than just heat; in fact, it would probably require the same mixture of hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorous, and sulphur, along with “methane, ammonia, formaldehyde, sulphides, nitriles and simple sugars,” that gave rise to life on our own planet.

Artist’s impression of early Mars with an atmosphere compared to Mars as it is now. Returning Mars to a ‘living’ planet would be an extremely long process, even if it was possible.

Artist’s impression of early Mars with an atmosphere compared to Mars as it is now. Returning Mars to a ‘living’ planet would be an extremely long process, even if it was possible.

As evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis demonstrated along with Earth scientist James Lovelock, these crucial substances are regulated by protobiotic life-forms themselves. That means that if we want to bring Mars to life, we’re going to need a planet’s worth of microbes, whose complex interactions will produce the conditions life needs to survive, flourish and evolve. And these microcreators would take anywhere between ten thousand and one hundred thousand years to shape Mars into the kind of planet across which big animals could walk or swim or hoverboard without a space suit. So it’s going to be a long time living in those shopping malls.

Should we do it (assuming we can)?

We might not know how to recognise life on Mars even if we looked straight at it

According to Zubrin, we not only should, we must. Rooted as he is in the long history of American conquest, Zubrin believes that “the creation of a new frontier [is] America’s and humanity’s greatest social need. Nothing,” he writes, “is more important.” Zubrin gets the idea from the early twentieth-century historian Frederick Jackson Turner, who argued that the identity of the United States has been fundamentally shaped by its progressive frontiers.

According to Turner, America gained a sense of itself apart from its European ancestors as it expanded from the Eastern Seaboard across the vast Midwest, up to the Great Lakes, down to the Mississippi delta and all the way out to the Pacific (“each,” he boasts, “was won by a series of Indian wars”). For Turner, each victory of the new nation over its European and Indigenous rivals contributed to America’s “perennial rebirth,” increasing the national character in strength, independence, energy and freedom. By the end of the nineteenth century, the conquest was complete, and the question for Turner in 1893 was how America could retain its character now that “the frontier has gone.”

For Zubrin, the answer is easy: it can’t. The signs, he insists, are everywhere: economic decline, technological stagnancy, bureaucracy and overregulation, reality television, loss of overall vigour: it’s clear the US is a nation in decline. We’ve got to get back to our roots, Zubrin cries, and our roots are on the open frontier. “Without a frontier from which to breathe life,” he writes in a tribute to Turner, “the spirit that gave rise to the progressive humanistic culture that America has offered to the world for the past several centuries is fading.”

The results of both NASA’s MAVEN and ESA’s Mars Express missions indicate that terraforming Mars could not be done with currently available technology and any such efforts would therefore be very far into the future.

The results of both NASA’s MAVEN and ESA’s Mars Express missions indicate that terraforming Mars could not be done with currently available technology and any such efforts would therefore be very far into the future.

In line with Johnson, JFK, Trump, and Pence alike, we might notice that Zubrin here is equating American flourishing with human flourishing. The US has offered the world a model of peace, decency, human rights and freedom, but it’s only the frontier that’s allowed the US to model those characteristics in the first place – or so the reasoning goes. “Without a frontier to grow in,” Zubrin insists, “not only American society, but the entire global civilisation based upon Western enlightenment values of humanism, reason, science and progress will die.” To his mind, the fate of any “humanity” worth mentioning rests on the fate of America, the fate of America rests on the opening of a new frontier, and “humanity’s new frontier can only be Mars.”

The Pathfinder rover on Mars inhospitable surface.

The Pathfinder rover on Mars inhospitable surface.

“Mars?” asks science journalist Shannon Stirone in an article that I’ve probably read fifteen times; “Mars is a Hellhole.” Responding to Elon Musk’s lust for immortality on the Red Planet, which is largely inspired by his mentor Zubrin, Stirone’s 2021 article for The Atlantic magazine cites the usual list of unsavoury Martian attributes: the lack of pressure, the freezing temperatures, the seeming lifelessness, the blood-boiling atmosphere. Mars, she argues, isn’t going to save us. “Mars,” she counters, “will kill you.”

For Zubrin, however, these atmospheric challenges are just what the languishing American spirit needs to reinvigorate itself. Every site on Earth is too easy, too decadent, not to mention too regulated to serve as a genuine frontier. Even in Antarctica, he says, “the cops are too close.” Venus is too damn hot. The Moon doesn’t have enough of the elements we need to survive. Mars, on the other hand, “possesses oceans of water frozen into its soil as permafrost, as well as vast quantities of carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, and oxygen, all in forms readily accessible to those clever enough to use them.”

And if we don’t act soon – here comes the urgency – we’ll lose the collective cleverness we need to figure it out. “Mars today waits for the children of the old frontier,” he says. But considering how stupid Americans are getting, how soft we’re growing around our pioneer edges, “Mars will not wait forever.”

If we want to bring Mars to life, we’re going to need a planet’s worth of microbes, whose complex interactions will produce the conditions life needs to survive, flourish and evolve

So we must act now. “Failure to terraform Mars constitutes a failure to live up to our human nature,” Zubrin writes. Should we succeed, however, we will not only fulfil this nature; we will surpass it. In the process of creating life on a dead planet, the (American-led) human species will approach divinity, making worlds out of nothing at all. “Gods we’ll never be,” says Zubrin, in the midst of the suddenly biblical flourish that culminates his Case for Mars, but we can become “more than just animals.” Terraforming the Red Planet will reveal humanity to be creatures who “carry a unique spark,” who are godly enough to provide a new planetary home for “the fish of the sea... the fowl of the air, and every living thing that moveth upon the Earth.”

Moveth! At the culmination of his “let’s terraform Mars” book, Zubrin cites not just the Bible but the King James Version, as if the arcane language might remind “humanity” of its God-given governance over “the fish of the sea” and every other creature. As if it might rekindle the “unique spark” of Genesis 1, which made Man in the image of God and now promises to make worlds in the image of Man. In case we’ve missed the point, Zubrin makes all these biblical references more explicit in a later article, writing that terraforming Mars would constitute “the most profound vindication of the divine nature of the human spirit – dominion over nature, exercised in highest form to bring dead worlds to life.” God’s Newest Israelites will be cosmic necromancers.

Younger advocates of terraforming, all of them influenced by Zubrin, tend to focus less on the power of creation than salvation. For these newer terraformers, Musk among them, the imminent danger we face is not just the decline of Western civilisation but the death of the human species itself. If some cataclysmic event was to wipe out life on Earth, they reason, everything worth anything would be gone. Therefore, it’s important to plant as many cosmic colonies as possible, to increase the likelihood that one of them might survive. This is what Musk means when he professes his “duty to maintain the light of consciousness, to make sure it continues into the future.”

Other advocates of terraforming go even further than Musk, expressing their intention to save not just humanity but life itself by giving it another place to take root. After all, when the Sun explodes in five and a half billion years, the game will be over for anything that eats, breathes or excretes. And sure, a dying Sun will do away with Mars as well as Earth. But Mars can serve as an eventual launching pad to another solar system. Therefore, as geologist Martyn Fogg concludes, “total extinction of terrestrial life can... only ultimately be avoided by vacating our planet for a more benevolent locale elsewhere in the cosmos.”

Planetary scientist Christopher McKay estimates it would take about 100 years to make the planet as warm as an ordinary springtime in Alaska

A more benevolent locale? Seriously, what are the chances? We don’t know a ton about the planets that orbit other stars, but the data so far isn’t all that promising. Some exoplanets seem to reach 1700F (927C). Some are losing their atmospheres to overactive solar radiation. Many of them orbit red dwarf stars, frigid little things that periodically fire forth solar flares to obliterate any life that might be trying to live. So, as Carl Sagan warned in the ecocidal 1990s, the “pale blue dot” we were born on – with its oxygen, nitrogen, liquid oceans, and plentiful sunshine; its forests and waterfalls and calling birds and fragile bees – seems still to be the most benevolent planet out there.

The first true-colour image of Mars generated using the orange (red), green and blue colour filters of the OSIRIS camera on the Rosetta probe, acquired in February 2007.

The first true-colour image of Mars generated using the orange (red), green and blue colour filters of the OSIRIS camera on the Rosetta probe, acquired in February 2007.

Perhaps we could resolve to terraform Earth, instead? In the words of astronomer and artist Lucianne Walkowicz, “If we truly believe in our ability to bend the hostile environments of Mars for human habitation, then we should be able to surmount the far easier task of preserving the habitability of the Earth.” Why not put all that money, energy, and manly frontierism into bringing our own ecosystem back to life?

Faced with this sort of argument, terraformers who claim to love their home planet (Musk is not among them) promise that hacking Mars will ultimately be good for Earth as well. With smart-sounding proposals like “comparative planetology,” they claim that figuring out how to bring life to another planet will also help us save life on this one.

Saving planet Earth

But this argument perplexes me. We already know what we have to do to save life on this planet. We have to reduce carbon emissions, stop using plastics, plant more trees, clean up the oceans, restore the rainforests, ban industrial farming, eat as little meat as possible, and divert subsidies away from oil and cars and toward public transportation.

We don’t need folks to aspirate on Martian dust and die of radiation poisoning in order to learn any of that. The terraformers just don’t seem to want to know what everybody knows, which is that the extraction, consumption, and runaway pollution that are wrecking life on this planet won’t suddenly become lifesavers when we export them to Mars.

Suspicious of the techno-tactics of terraforming, some of the more ecologically sensitive spaceniks suggest an alternative in ecopoiesis. Literally meaning ‘home building’, initiating ecopoiesis would mean sending a flood of microbes and chemicals to do the long work of allowing more complex life to evolve (or not) on Mars.

The extraction, consumption, and runaway pollution that are wrecking life on this planet won’t suddenly become lifesavers when we export them to Mars

Far from turning the planet into the terraformers’ shopping mall, garden paradise, or cosmic amusement park, Margulis explains that ecopoiesis “would transform [Mars] into a global cesspool – colourful, perhaps, but rich in mephitic vapours” and smelling like “sewer gas.” Such a protobiotic planet would not in any sense be for humanity – at least not for tens of thousands of years – but it might well be in service of some sort of life. So perhaps instead of sending rovers and drills and refineries, we should send the primordial ‘goo’ and see what happens.

A Mars Society conception of a terraformed Mars.

A Mars Society conception of a terraformed Mars.

As far as Carl Sagan was concerned, it all depends on what’s on Mars in the first place. Most arguments in favour of terraforming and ecopoiesis assume that, although life may have existed on Mars in the past, it no longer does. But it’s always possible that microscopic creatures are hiding somewhere under the ground or inside the rocks. And in that case, Sagan wrote, “if there is life on Mars, I believe we should do nothing with Mars. Mars then belongs to the Martians, even if the Martians are only microbes.”

As astrobiologist David Grinspoon has argued, however, our understanding of ‘life’ is based exclusively on terrestrial biota. We might not know how to recognise life on Mars even if we looked straight at it. So at what point would we decide Mars is sufficiently ‘dead’ to ecopoieticise it or terraform it? How would we ever know we weren’t interfering with the native biotic processes of Mars?

For Zubrin and Musk, it doesn’t matter. Whatever microbial life might exist in a frozen rock on the Red Planet, it’s nothing compared to the complexity of terrestrial vegetation, animal diversity and human arts on this blue-green one. So, we have an obligation to spread our earthly kind of existence, no matter what sort of existence Mars might be trying to sputter out.

At this point, a whole new coalition of ethicists begins to protest, telling us to leave the rocks alone.

This article is based on an extract from Astrotopia: The Dangerous Religion of the Corporate Space Race by Mary-Jane Rubenstein and published by The University of Chicago Press. It is reprinted with permision and all rights are reserved.

This article is based on an extract from Astrotopia: The Dangerous Religion of the Corporate Space Race by Mary-Jane Rubenstein and published by The University of Chicago Press. It is reprinted with permision and all rights are reserved.

About the author

Mary-Jane Rubenstein is Dean of Social Sciences and Professor of Religion and Science in Society at Wesleyan University. She is the author of several books including Pantheologies: Gods, Worlds, Monsters (Columbia University Press, 2021), Worlds Without End: The Many Lives of the Multiverse (Columbia University Press, 2015); and Strange Wonder: The Closure of Metaphysics and the Opening of Awe (Columbia University Press, 2010). She is also co-author of Image: Three Inquiries in Technology and Imagination (University of Chicago Press, 2021), and co-editor of Entangled Worlds: Religion, Science, and New Materialisms (Fordham University Press, 2017).