Buried underneath the allegorical plot-lines of all those Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica episodes is a very simple and uncomfortable fact that humanity as a whole does not often like to acknowledge: a single-planet species is ultimately doomed to extinction.

Everything in the observable universe tells us that this is a matter of when, not if. Whether it is the asteroid that ended the reign of the dinosaurs, or a telescopic glimpse of dying stars expanding to the point that they devour nearby planets, the universe is constantly reminding us of the fact that life limited to the confines of one planet is ultimately doomed.

Although the possibility of extinction is not a topic on which most of us like to dwell, the issue of humanity’s ultimate survival is, in one way or another, given a nod by most science fiction that deals with the topic of multi-planet civilizations. The Star Trek franchise essentially sprung from the notion that in order for humanity to better itself - as opposed to festering and waging senseless intra-species wars - it had to, both metaphorically and physically, reach for the stars.

The Star Wars franchise, on the other hand, is different, derived from mythological archetypes-arguably helping us to process our past, as opposed to a possible future-and famously set in ‘a galaxy far, far away’, with no planet Earth even mentioned. Both of these classics, however, directly and indirectly address the inherent fragility of a single-planet civilization.

Throughout its long and varied history Star Trek did this in different ways, some of them quite subtle. Perhaps one of my favourite episodes addressing this was Star Trek: Voyager’s ‘Friendship One’, set on a planet suffering from nuclear winter that came about as the result of the planet’s residents utilising information from an aging Starfleet probe improperly. The idea of a civilization crippled by a technology whose power it could not initially understand - and vying for the chance to relocate - can resonate deeply with anyone who has considered the risks of nuclear war and its consequences on planet Earth.

Although the possibility of extinction is not a topic on which most of us like to dwell, the issue of humanity’s ultimate survival is, in one way or another, given a nod by most science fiction

Even in the Star Trek universe, which frequently makes technological progress seem laughably effortless (often invoking convenient MacGuffins to advance the plot), the process of safely relocating an entire planet’s population is stated to be as long as three years. And although the starship Voyager has the necessary technology to ‘fix’ the planet’s nuclear apocalypse, the intense yearning of some among the native population to leave is made central to the episode, with dramatic consequences. Leaving is hard, we are told. Leaving could even be irresponsible. This dilemma isn’t likely to be presented to the human race in the near future, but when it does, it is bound to be difficult, as Star Trek reminds us.

Star Wars, being a much less sprawling franchise, has dealt with the dilemma of single-planet populations in much more dramatic ways. Who can forget the (now quite meme-tastic) destruction of the peaceful planet Alderaan, and its nearly two billion inhabitants, by the evil Galactic Empire? I say ‘nearly two billion’, because Star Wars lore points to the fact that at least 60,000 or so residents of Alderaan were away from the star system at the time the infamous Death Star unleashed its death ray upon the planet.

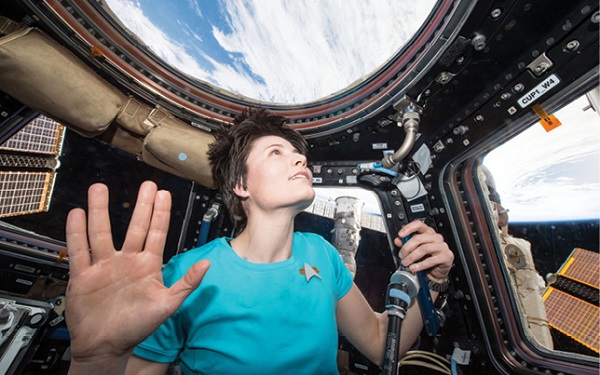

Space Station astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti pays tribute to actor Leonard Nimoy who played Spock in the original series of Star Trek

Space Station astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti pays tribute to actor Leonard Nimoy who played Spock in the original series of Star Trek

Alderaan has inspired a number of allegorical interpretations, but perhaps the chief meaning of its destruction is relayed in the famous quote by Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi, ‘I felt a great disturbance in the Force, as if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror, and were suddenly silenced. I fear something terrible has happened.’ The destruction of an entire world - one which the viewer does not even observe in the course of the original Star Wars Episode IV film - would appear to be practically an invocation of another famous quote, one that is frequently attributed to Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, ‘A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.’

Robot C3PO from the film Star Wars

Robot C3PO from the film Star Wars

No historical record of Stalin uttering these words actually exists. But it’s true that for the casual observer of the Star Wars universe, what happened to Alderaan can feel impersonal, even though extended Star Wars lore points to a variety of repercussions for the wanton act of genocide on the part of the Empire.

The Star Wars universe reminds us that a civilization can defiantly go on - provided it has both the technology and the will to do so

The fact that Obi-Wan sensed the event, and the fact that Leia, at that point a Princess of Alderaan, was forced to witness the horror, leant an immediate emotional dimension to the proceedings. More importantly, in follow-on Star Wars novels (which were considered canonical until Disney’s purchase of Lucasfilm), the off-world survivors of the destruction of Alderaan founded two successive colonies after their planet was destroyed. While there is tremendous symbolic power in the violent destruction of a planet, the Star Wars universe reminds us that a civilization can defiantly go on, provided it has both the technology and the will to do so. Alderaan culture and its people continued because when their home planet was destroyed, they were elsewhere.

In light of Star Trek and Star Wars dramas, environmental concerns that force a civilization to relocate can seem almost boring, yet on a real-life Earth currently struggling to come to terms with the notion that human-induced global warming is real, they are no less important to a multi-planet storyline.

In Joss Whedon’s Firefly space western series, which eventually also resulted in the film Serenity - the excellent cinematic continuation of the equally excellent show - the environment is almost casually, yet forebodingly, present.

In the show’s back story, Earth’s resources were depleted, as both the series and the film continually remind viewers. Many themes overlap within Firefly and in the film Serenity, yet one constant theme runs alongside all of the elegant plot twists we’re presented with - if you’re going to tirelessly consume and expand, your species will be forced to relocate to a new star system, and who knows what awaits you there? Everything from war to disastrous attempts to subdue a population, as it turns out.

By adapting the trappings of a Western, the Firefly universe hammers another point home: relocation for the purposes of survival is messy. Values shift, new alliances are forged. An entire realignment of a population’s priorities can take place - and if that population is scattered among different planets, feuding and battle are likely to take place eventually.

‘You can’t take the sky from me’ is the penultimate line of Firefly’s theme song. Meant to invoke the old-school themes of a classic Western, with its emphasis on personal freedom, self-determination and the occasional shoot-out, it is also a powerful reminder of a multi-planetary civilization’s ultimate ideology of limitlessness and freedom of movement.

Rey and BB-8 droid in Star Wars: The Force Awakens

Rey and BB-8 droid in Star Wars: The Force Awakens

Mobility, of course, is the single most important factor to a multi-planetary civilization’s survival. The importance of mobility is beautifully exemplified by such tense and at times claustrophobic shows as Battlestar Galactica and Farscape. The former in particular shows how, at times of devastation, a spaceship can become a vehicle for life and sustainability. When your enemies out number and overpower you, you flee.

There are many terrific interpretations of the Battlestar Galactica universe, but one of my own favourite ways of looking at it is through the prism of ancient history and humanity’s nomadic way of life. Our nomadic ancestors took what they could from the land and moved on - and while things are a tad more complicated in the Battlestar Galactica universe, the idea of constant movement for the sake of survival carries particular emotional weight for the franchise precisely because humanity itself knows what it is like to have to be on the move. This is a show that reminds us of what our ancestors already knew: being able to settle down is a privilege but it is also a risk. Both emotional and practical attachment to one place leave a society vulnerable.

Before you take a leap, it’s always a good idea to consider both why you’re doing it and where it is that you will ultimately land

In Farscape, a show very much enamoured of biological diversity, survival as a nomad is given an extra, powerful dimension via the ship the cast of characters resides on. Bio-mechanical spaceship Moya is as alive as any of the other characters on the show - so alive that she can give birth and suffer horrifically when her child eventually chooses to die in order to save his mother and her crew.

The choice to have a living vessel on Farscape - not a simple hunk of metal but an entity that can think and feel - is important in the context of survival. When we consider our own desire for our species to not become extinct, to persevere, to go on to new worlds, we must consider the simple question of, ‘To what end?’ It is Moya, as well as her son, Talyn, that rather nicely embody the answer. It is not enough to simply go on. If you go on simply as a plague of locusts does, without having both appreciation and respect for your surroundings, your existence doesn’t have much meaning, and its continuation is unimportant.

Plenty have argued that we should not even distinguish between humanity and your typical locusts. Both are organic. Both need to consume. In fact, I would argue that the very utilitarian thinking that proposes we simply ignore our impact on our home planet is de-humanising precisely because it would have us treat ourselves as just another invasive species, stripped of all responsibilities simply because its biological imperative is to thrive by any means necessary.

Humans, however, are slightly more complex than locusts. Our ability to reason, to employ abstract thinking, to exhibit altruistic tendencies and cooperation skills, alongside our more violent and destructive instincts, all bestow upon us a responsibility to think before we act. To weigh consequences. Farscape’s living Moya could very well be a stand-in for our own Earth. It is fragile, it is finite - and even when we are forced to depart from it, we must give it its due.

Spaceship Pegasus from Battlestar Galactica

Spaceship Pegasus from Battlestar Galactica

All the fictional universes I’ve described can be dismissed as far-fetched fantasies - created for the purposes of escapism alone - but arguably they address both our desire to survive and the many twisted and not-so-twisted ways to achieve that end.

Our technological capabilities do not yet allow us to cover great distances, but the rapid progress of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century show that humanity is perfectly capable of taking giant leaps as far as knowledge and the utilisation of knowledge are concerned. Before you take a leap, it’s always a good idea to consider both why you’re doing it and where it is that you will ultimately land.