Jan Woerner is no stranger to the international space scene. Between March 2007 and June 2015 he served as Chairman of the Executive Board of the German Aerospace Center (DLR). And, before joining as ESA Director General last summer, he headed up Germany’s ESA delegation after serving as chairman of the ESA Council between 2012 and 2014.

As such he knows ESA pretty much inside out and seems exactly the right person to inject fresh vigour and guide the agency into a new area of space exploration, building on the astute achievements of predecessor Jean-Jacques Dordain. In the nine months since assuming the role of Director General he has already begun to make his mark.

Plans to construct a lunar base - which might also serve as a staging platform for future missions to Mars and beyond - were outlined at an international symposium at ESTEC (the European Space Research and Technology Centre) in Noordwijk, The Netherlands, at the end of 2015. The symposium, ‘Moon 2020-2030 - A New Era of Coordinated Human and Robotic Exploration’ was the ideal platform for Woerner to articulate his vision.

He’s something of a catalyst and likes to paint pictures. “Okay,” he says. “So ‘Moon village’ is a synonym for a new type of exploration and corporation. Of course, it’s not a village in that we will build some houses and a church and a city hall and maybe a conference centre - that is not the concept.

“The idea is to put together different actors with different abilities to achieve something better - this can be human activities or robotic activities of different kinds. I think the Moon is an interesting object from a scientific point of view and the far side is even more interesting for a telescope, so we can put together several activities, astronomy, even tourism and then have it as a new international corporation. That is my idea.”

So, will this become the basis of a formal proposal? Not according to Woerner, explaining that such thinking is not comparable to the 1960s when John F Kennedy launched the US on a fast-track and competitive lunar trajectory. “The situation is very different today,” he explains. “Maybe it’s me throwing out the idea first,” he suggests. “Now we are ‘jamming’, which means all the different actors worldwide are throwing their ideas on the table, saying okay this is good, this is bad.

At the end of the day I hope we’ll have a full understanding of what we can achieve together

“At the end of the day I hope we’ll have a full understanding of what we can achieve together. If it’s a Moon village, as I propose, that’s fine, if it’s another solution but with the same advantages or even better then I would be happy.”

The International Space Station (ISS) has brought spacefaring nations together in an unprecedented endeavour of international cooperation but, according to Woerner, the future of space travel needs a new vision.

“Right now we have the Space Station as a common international project but it won’t last forever. Based on all the experience we are gaining with the ISS, good and bad, we should look for a common international exploration activity for the future,” he says.

“In a Moon village we would combine the capabilities of different spacefaring nations, using both robots and astronauts. Participants could work in different fields, perhaps they will conduct pure science and perhaps there will be industrial and business ventures.”

In Woerner’s vision the “been there, done that” view of the Moon does not arise. “No human has ever visited the far side of the Moon,” he says. “Astronomers want to set up radio telescopes there because it is shaded from Earth’s radio pollution. Building a telescope, perhaps using innovative techniques like 3D printing, would enable us to look much deeper into the universe.

“No human has ever visited the lunar pole regions, where unmanned missions have discovered water ice,” he continues. “This is an important resource because you can produce rocket propellant and oxygen from it. Both lunar polar regions are scientifically very promising places. A Moon village would also act as a ‘pit stop’ for the further exploration of the Solar System.”

Woerner sees much of his immediate role within ESA as interacting closely with stakeholders and shareholders to properly define future space activities. “Space agencies are facing several shifts of paradigm when it comes to commercialisation and a broadening of activities,” he observes. “This means the role of agencies will also change. Agencies will remain the strong financial providers for some areas, such as fundamental research, but will become the enablers, brokers and mediators for other areas.”

ESA serves both its member states (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom) and the European Commission (EC) at the same time. In addition, Canada, Bulgaria, China, Cyprus, India, Malta, Latvia, Lithuania, Russia, Slovakia and Slovenia have cooperation agreements.

Artist’s impression of a future lunar settlement

Artist’s impression of a future lunar settlement

“According to our convention, ESA should elaborate a long term plan,” says Woerner. “ I hope, that rising above all vanities, we will come to agree a single European space strategy defined jointly by ESA and the EC, and representing the parallel competences of all member states.”

Likening space to a ‘safety valve’ for humankind, he adds: “Space is right now an infrastructure which will be continuously developed. At the same time the inspiration of exploration is of utmost importance to secure the future through motivated people.”

Asked whether the space industry has become too risk averse when defining new projects, Woerner says not in all parts. But he certainly believes this could sometimes be a justifiable criticism levelled at projects that originate in the ‘public domain’. “People are afraid because they are spending taxpayer’s money,” he states. “But the example of Rosetta demonstrates that the public likes to see risky activities, which shows curiosity as one of humanity’s strongest drivers.

“To be risk adverse is not the right thing for the future,” he states. “So we need disruptive ideas and we have to allow them.”

During his tenure as ESA DG Woerner expects to witness significant break-throughs across different scientific disciplines, including in material sciences, control systems, engine and thruster systems. He expects national space agencies will increasingly redefine their roles and strengthen their abilities to act as brokers and enablers on space projects at different levels.

“If you expect something then you have already paved the way,” he says. “I hope for many break-throughs in all fields. Of course, launchers are a central part of this because it is not acceptable that launch costs remain such a high proportion of a mission. And, concerning science, the fact that 95 per cent of the universe is ‘hiding’ behind dark energy and dark matter gives plenty of room for hope and expectation. And, from industry, I hope to see more responsible actions to keep schedules and costs in pre-defined limits.”

Woerner believes it is important to advance on the path of space exploration and to him this is a central driver. “We do it not just for science and for technology but also for inspiration and international cooperation. And going to the Moon – this time in a totally different manner – would meet all these criteria. Additionally, it could help with planetary defence, which means protecting Earth from the hazards of impacting asteroids or comets. To venture into the unknown is in our genes, curiosity has always been a very strong driver for humankind. And exploration is especially part of the European heritage.”

Convivial but not always willing to tow the politically correct line, Woerner is prepared to pitch his European voice against NASA. And when it comes to Mars, he expresses a degrees of doubt that crewed missions to the red planet will be achieved anytime in the next three decades.

“There are several reasons,” he explains. “One, we don’t have the technology right now to go to Mars and back. Okay this can be built but even then the consideration of such a mission is going to be something like two years to go there and back. It’s not just technical problems but we would have to deal with health issues. Just say you get a painful illness after a month - what do you do? I mean minor surgery you can do but a major one would be really difficult.”

Paraphrasing Antoine de Saint Exupéry, the French writer and pioneering aviator, Woerner says his task as ESA DG is not necessarily to foresee the future but to enable it. His ideas will certainly be put to the test in the coming years and months. Among them is his often-expressed belief that a European nation’s support for an ESA programme should be based on that programme’s inherent appeal to the nation and not on the kind of horse-trading that often gets ESA missions funded. “The idea that I’ll support your favourite mission if you support mine is something we really need to get beyond,” he says.

But, against a backdrop of political instability for the wider European project - hampered by the ongoing refugee crisis, terrorism, currency fluctuations and a British in-out EU referendum in June - Woerner sees the need for integration as of even greater importance.

Any attempt to communicate in a negative manner or claim overall governance would result in deadlock and may in the end prove detrimental

ESA has an increasing role to play in procuring and promoting the continent’s space aspirations and amongst any wider political turmoil one question that will continue to demand close attention is relations with the European Commission.

“There is a tendency to prioritise national activities and a certain euro-scepticism is in evidence,” he states. “Fortunately, this tendency has had little impact on ESA, as the way in which the agency operates is very supportive of diverse interests and industrial policies. It follows, therefore, that we should make our next goal a ‘United Space in Europe’. To achieve this, pragmatic, transparent and reliable cooperation among the main space actors in Europe is of the utmost importance.”

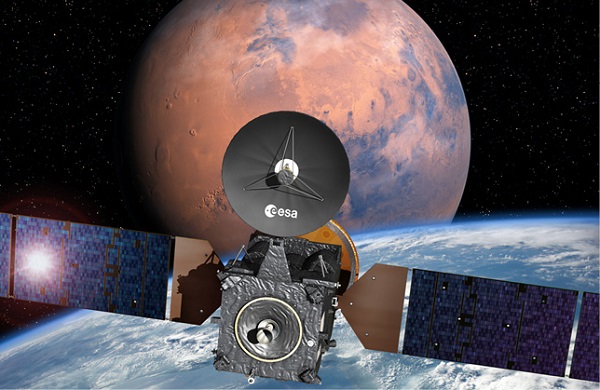

Artist’s impression depicting the ExoMars 2016 entry, descent and landing demonstrator module, named Schiaparelli, on the Trace Gas Orbiter, and heading for Mars. Separation at the red planet is scheduled to occur on 16 October 2016, some seven months after launch. Schiaparelli will enter the Martian atmosphere on 19 October, while TGO will enter orbit around Mars.

Artist’s impression depicting the ExoMars 2016 entry, descent and landing demonstrator module, named Schiaparelli, on the Trace Gas Orbiter, and heading for Mars. Separation at the red planet is scheduled to occur on 16 October 2016, some seven months after launch. Schiaparelli will enter the Martian atmosphere on 19 October, while TGO will enter orbit around Mars.

Within ESA itself, the relationship between ESA activities and the activities of member states constitutes a solid foundation laid down by the ESA Convention, paving the way for interaction and effective cooperation. There are also existing relations between ESA and EUMETSAT (European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites) and other organisations.

“At the same time,” explains Woerner, “there is a clear need to develop similarly effective relations with the European Union and, more specifically, with the European Commission. Instead of arguing over commas in legal documents, we should seize the opportunity to create coherent cooperative mechanisms that take full account of our respective experience, mandates and capabilities.

“Any attempt to communicate in a negative manner or claim overall governance would result in deadlock and may in the end prove detrimental to European citizens and to space activities in particular.

“Citizens and politicians alike expect us to approach our interactions at institutional level with great seriousness, as well as carrying out advanced, inspiring and educational European space activities - rather than engaging in quarrels over details about who has the power in whichever area. There is much important work to be done.”