Canadarm, the first robotic manipulator system designed specifically for use in space, was installed and used on each Space Shuttle from the second flight on, for 30 years until the end of the Shuttle programme in 2011. Its successor, the bigger, more complex Canadarm2, was extensively involved in the in-space assembly of the International Space Station (ISS). In the 20 years since it was first deployed the robotic arm, together with Dextre, a two-armed robot, has developed far beyond its early parameters, enabling the ISS programme to use it in unpredicted ways, including capturing free-flying cargo vehicles to berth them to the ISS. Tim Braithwaite takes us on a journey from the early days of Canadarm2 to a glimpse of what is to come with Canadarm3.

In March 2001, a newly minted Canadian flight controller rode the elevator down to the International Space Station (ISS) Flight Control Room on the first floor of NASA’s Mission Control Center in Houston. The ink was still drying on the paperwork – his own Robotics Operations Officer (ROBO) certification and that of his teammates (Mobile Servicing System (MSS) Systems and MSS Task) – upstairs in the Robotics Support Room. Starting that night and for the next few weeks, representing the tip of a massive iceberg of ingenuity, effort and expertise, this team of two Canadians and one American would be the ISS’s only certified robotics flight controllers... and they had work to do.

Two nights later, orbiting 380 km above Earth, the ISS crew unpacked and assembled the first robotics workstation in the ISS Destiny laboratory. Canadarm2 would launch in a month, and the flight controllers had that time to check out the new hardware. That night, though, they had one objective: to confirm that a video feed routed from a camera on the Space Shuttle – docked to the ISS – would appear on a monitor on the new ISS robotics workstation. Vital to every robotics assembly mission to come, this simple step had never been done before and had to be checked out.

The arrival of Canadarm2 on the ISS is part of an evolutionary thread that traces back to the 1970s. Canadian participation in the United States’ Space Shuttle programme sprang from the US’s desire for cooperation in human space flight after Apollo, and in 1975, the US and Canada signed an agreement for Canada to develop a robotic arm for the US Space Shuttle.

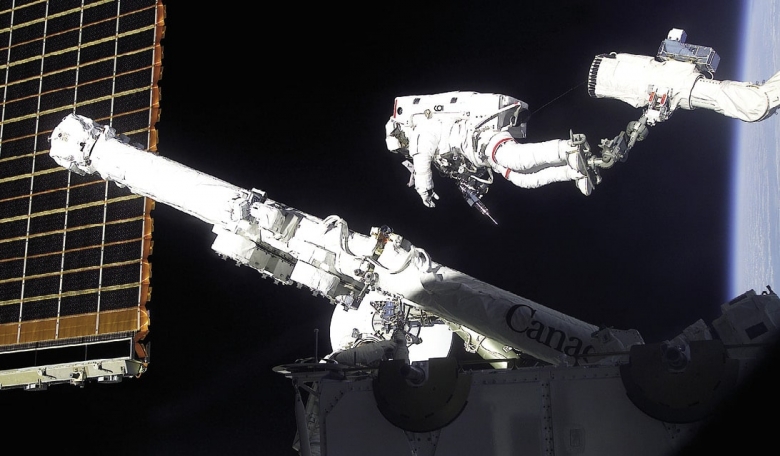

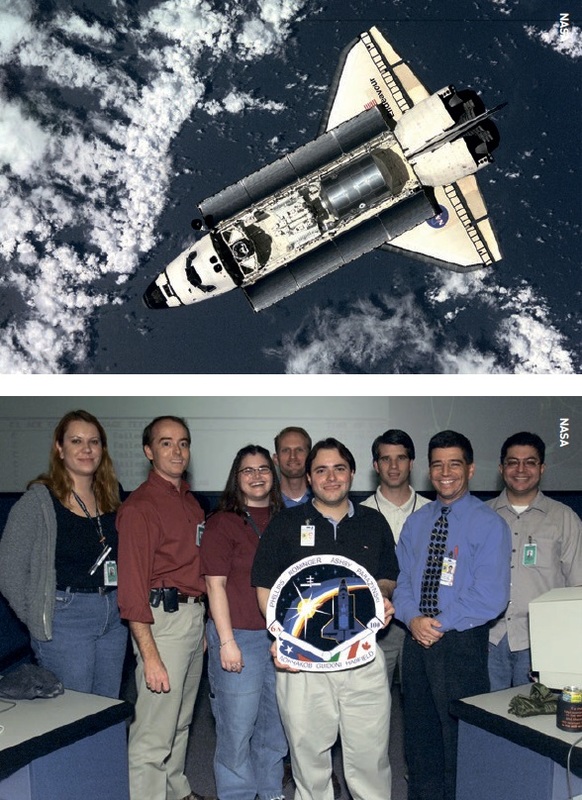

Canadarm on Space Shuttle mission STS-2 in November 1981.

Canadarm on Space Shuttle mission STS-2 in November 1981.

The Space Shuttle arm became a Canadian government programme, led by the National Research Council of Canada with Spar Aerospace (later to become MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates (MDA)) as the prime contractor. Under the terms of the agreement, Canada developed and delivered the first arm, and NASA procured three more from the Canadian industry team. The Spar Aerospace team went on to provide sustained engineering support for the duration of the three decade Space Shuttle programme.

The first Canadarm launched on only the second Space Shuttle flight, STS-2, conducting unloaded arm tests on 13 November 1981. By the time STS-135 landed in July 2011, ending the Space Shuttle programme, Canadarms had supported more than 60 Shuttle missions.

In addition to assembling the ISS, these missions serviced the Hubble Space Telescope, deployed and retrieved satellites, manoeuvred spacewalking astronauts, performed critical surveys and a number of improvised tasks only made possible by Canadarm’s flexibility – including some capabilities that the Space Shuttle programme never knew it needed. All this set the precedent for the extraordinary success of Canadarm2.

The first Hubble servicing mission.

The first Hubble servicing mission.

Canadarm2 and the MSS

Canada’s contribution of the Space Shuttle arm had been a boon for Canadian industry and had created flight opportunities for Canadian astronauts

In 1984, the US invited international friends and allies to join them in the Space Station programme. The success of Canadarm on the Space Shuttle led naturally to a study of potential Canadian participation in the programme. Marc Garneau’s first flight on the Space Shuttle that year fostered an even more favourable climate across Canada for Canadian involvement. Canada’s contribution would be a suite of space robots for Space Station assembly and maintenance. The MSS would include Canadarm2, the Mobile Base, and Dextre, a two-armed dexterous robot. Formal agreements were signed on 29 September 1988 – the same day that the Space Shuttle returned to flight, ending the two-and-a-half-year hiatus following the Challenger accident.

The intention to create the CSA had been announced in the Speech from the Throne in October 1986. The new agency was created on 1 March 1989, by which time detailed MSS design work was already underway with Spar Aerospace Ltd as the prime contractor.

As events unfolded with the flight controllers in NASA’s Mission Control on the night of 12 March 2001, Canada’s Space Agency was only 12 years old.

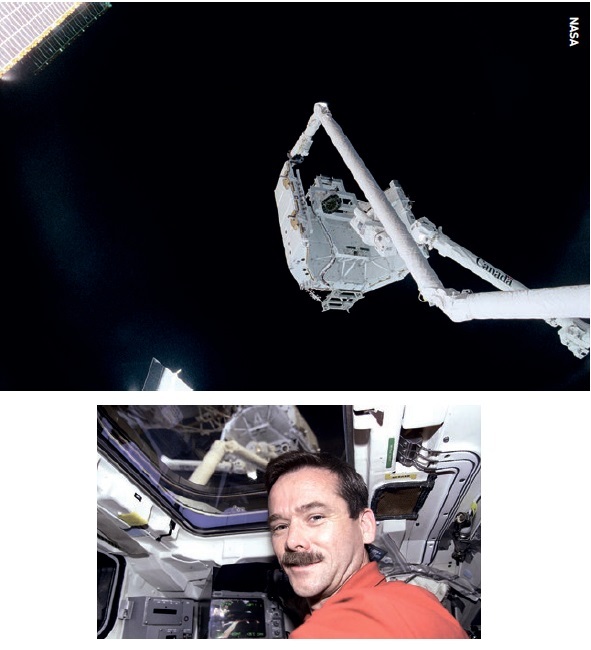

Top: Canadarm2 arrives at the ISS on Space Shuttle Endeavour on 21 April 2001. Above: Members of the ISS-6A ROBO team (from left): Danielle Cormier, Tim Braithwaite, Teri Rorabaugh, Michael Wright, Aaron Goldenthal (holding the mission plaque), Ian Mills (Flight Director), John Curry and Sarmad Aziz.

Top: Canadarm2 arrives at the ISS on Space Shuttle Endeavour on 21 April 2001. Above: Members of the ISS-6A ROBO team (from left): Danielle Cormier, Tim Braithwaite, Teri Rorabaugh, Michael Wright, Aaron Goldenthal (holding the mission plaque), Ian Mills (Flight Director), John Curry and Sarmad Aziz.

Arrival of Canadarm2

By the time Canadarm2 launched on Space Shuttle Endeavour on 19 April 2001, two more ROBOs had completed their certifications, along with the support teams they would lead. With three full teams, they could support the docked mission around the clock.

As well as Canadarm2, Endeavour carried Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield. He would deploy the arm out of its launch pallet, in the process becoming the first Canadian to perform a spacewalk. The flight had ample other Canadian content, with CSA astronaut Steve MacLean serving as the Shuttle’s CAPCOM in the Shuttle Control Room. On the ISS side, Danielle Cormier and Tim Braithwaite (the two Canadians from that first shift back in March) were joined by Sarmad Aziz and six of their American colleagues.

In addition, an integrated team of CSA & MDA engineering and programme staff was deployed both at the CSA in Saint-Hubert, Quebec, and on location at NASA’s Mission Control in Houston.

The day of the flight’s first spacewalk, 22 April 2001, was a milestone for Canada and an important step for the on-orbit assembly of the arm. Based in the Shuttle control room, Steve MacLean had placed a Canadian flag on every console as well as in the ISS control room.

With the spacewalk mostly complete, Hadfield ready to ingress the airlock, and the ISS flying over Newfoundland, MacLean had ‘O Canada’ played over the air-to-ground radio. He used a recording of Roger Doucet singing the national anthem before a Canadiens game at the Montreal Forum. This is thought to have been the first time any national anthem was played in space.

Between the unexpected demand for robotics support to external payloads and the increasing frequency of ISS maintenance, use of Canadian robots has gone up and up

Wearing a Canadian Olympic hockey sweater, MacLean stood at his CAPCOM console for this very Canadian moment! Hearing the music on the voice loops, Braithwaite rose and stood at the ROBO console in the ISS Control Room. Hadfield, floating outside the ISS, saluted.

Down the corridor in Mission Control, the CSA’s real-time programme office representative, Bill Mackey, was in NASA’s ISS Management Center... and he too had his hands full. In March, Mackey had set up the CSA’s IPCanada (International Partner Canada) console, responsible for communicating programmatic and technical issues to NASA’s management team. He was also helping establish the robotics real-time engineering support team, which during this pivotal mission hosted additional system experts from prime contractor MDA.

With the spacewalks completed, and the arm assembled and attached to the Station, there were handshakes all around and Bill broke out the maple cookies – a tradition that continues 20 years later for major events. Then the ISS main control computer failed. The redundant computer took over, but also failed... as did the third string.

Suspicion quickly spread that the newest addition to the ISS – Canadarm2 with all its complex software – was somehow causing the problem. It was later found that simultaneous hardware and software failures in the ISS computers caused them all to fail within a short time. This exonerated Canadarm2; however, the team still had to manage the multiple failure case and complete the mission.

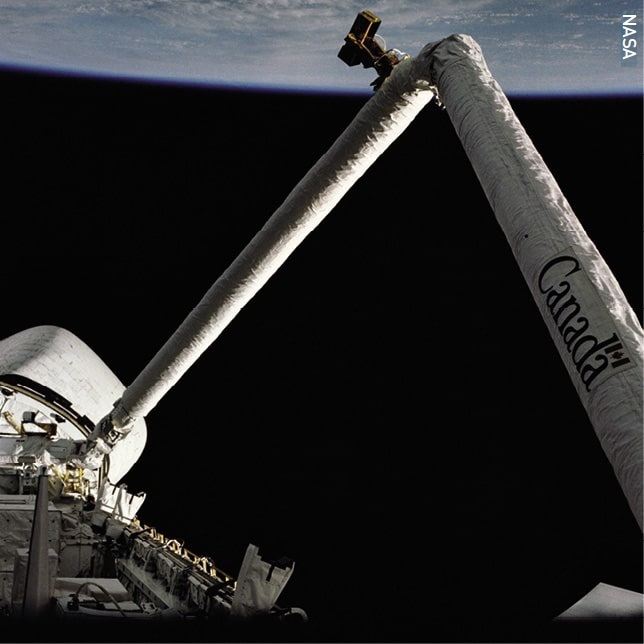

The ‘handshake in space’ – Canadarm2 hands its launch cradle back to the Shuttle’s Canadarm (April 2001) with Chris Hadfield (left) at the controls.

The ‘handshake in space’ – Canadarm2 hands its launch cradle back to the Shuttle’s Canadarm (April 2001) with Chris Hadfield (left) at the controls.

Robotic handshake

Despite the disruption, the team worked around the problems. Finally, with the ISS crew operating the Station’s new robotic arm from the US Lab module and Hadfield in the Shuttle, the ‘handshake in space’ took place. Canadarm2, based on the US Lab module, picked up the structure in which it had ridden to orbit and handed it back to the Shuttle arm, which stowed it in the payload bay. That same launch cradle would carry Dextre into space seven years later. Endeavour undocked from the ISS the next day.

The robotics operations that had begun in March with workstation checkouts quickly escalated to a new level of intensity with the complex commissioning process of Canadarm2 – all in preparation for installation of the US Quest airlock in July. The airlock would be the first of 34 new elements handled by Canadarm2 which, along with the Shuttle’s Canadarm, would go on to build the Space Station.

ISS partnership

Having a robotic arm on the Station has allowed the ISS programme to discover new flexibility and capabilities it hadn’t known it needed

Canada’s contribution of the Space Shuttle arm had been a boon for Canadian industry and had created flight opportunities for Canadian astronauts. In addition to these benefits, Canada became a full partner space agency – the first to join the US and Russia at the ISS programme table. More Canadian flight controllers were added as the ROBO team grew, forging a unique bilateral working partnership.

Within a few years, the CSA’s headquarters in Saint-Hubert on the South Shore of Montreal hosted its own robotics support room for Canadian flight controllers, as well as facilities to host the CSA’s and MDA’s engineering support, training and payload operations teams.

The CSA’s science research focused on human health and benefitted from partnering with the other agencies. The CSA’s valued partnership with NASA resulted in more Canadian astronaut flights on the Space Shuttle as well as long-duration missions on the ISS.

Canadarm2 manoeuvres the US Quest airlock for installation on the ISS, July 15, 2001.

Canadarm2 manoeuvres the US Quest airlock for installation on the ISS, July 15, 2001.

The CSA’s Remote Multi-Purpose Support Room in Saint-Hubert.

The CSA’s Remote Multi-Purpose Support Room in Saint-Hubert.

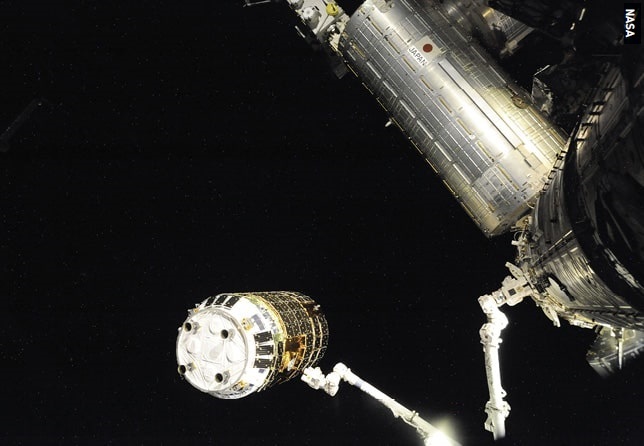

Canadarm2 captures the ISS’s first free-flying cargo vehicle, Japan’s HTV-1, in September 2009.

Canadarm2 captures the ISS’s first free-flying cargo vehicle, Japan’s HTV-1, in September 2009.

Evolution

Operation of Canadarm2 and Dextre has completely changed since those first components arrived on the ISS. The original MSS operations concept was based on how the shuttle arm had been operated, with astronauts driving at every step. However, years of intensive effort by the extended robotics team resulted in Ground Control, whereby arm motion is commanded from the ground. This allows flight controllers to operate the MSS from the ground the vast majority of the time, which in turn allows astronauts to focus on scientific research. This pivotal new capability was conceived and implemented after the arm was already in space.

The CSA’s robotics support room consistently supports more than 100 days of operations every year, while the Saint-Hubert Operations Engineering Centre has provided real-time engineering support for every single arm operation since 2001. Working with its American and Japanese partners, the CSA also added the capability to capture free-flying cargo vehicles. As of April 2021, Canadarm2 has captured 44 vehicles since the first (Japan’s HTV-1) in 2009.

Other enhancements, inspired by the experience of working on the ISS, have made the system much more robust. As with the Space Shuttle programme decades before, having a robotic arm on the Station has allowed the ISS programme to discover new flexibility and capabilities it hadn’t known it needed. Between the unexpected demand for robotics support to external payloads and the increasing frequency of ISS maintenance, use of Canadian robots has gone up and up.

In 2019, the joint Canadian-US flight control team operated the MSS on 170 days and sent it more than 100,000 commands. Arm usage was so high that Canadarm2’s end effectors (its hands) finally wore out, far exceeding their design life. Spacewalking astronauts replaced those parts, further proving the maintainability of the system and driving a massive hardware and logistics effort to manage and refurbish the spare parts flying to and from space.

Each milestone and system improvement has required huge effort from the CSA and MDA hardware, logistics, software, flight products, and analysis teams, under the leadership of the CSA’s ISS programme. The real-time operations team in the NASA and CSA Control Rooms represents just the tip of an iceberg that extends from Houston to Montreal to Toronto and beyond.

As the third decade of MSS operations begins, Canada is now developing autonomous control of its ISS robots. This autonomy will become the basis for future designs and operations. The CSA, MDA, and the Canadian robotics system itself have been evolving since the beginning. The ISS programme’s dynamic and constant operations environment has driven much of that evolution, with the CSA and its industry partners elevating Canadian robotics capabilities to new levels.

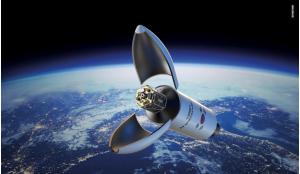

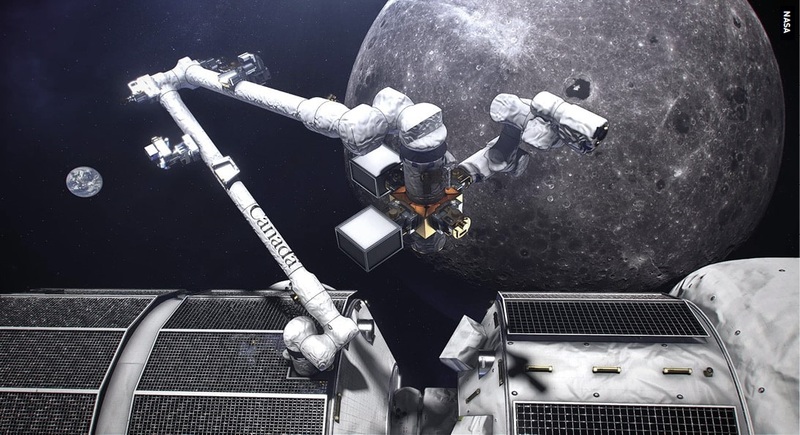

Concept for Canadarm3, Canada’s smart robotic system for the Lunar Gateway.

Concept for Canadarm3, Canada’s smart robotic system for the Lunar Gateway.

Lunar Gateway

Years of intensive effort by the extended robotics team resulted in Ground Control, whereby arm motion is commanded from the ground

Fifteen years after that first ROBO shift on console (on 11 March 2016), NASA astronaut and ISS Commander Tim Kopra called down from space with a message of congratulations on the 15th anniversary of that first certified ROBO team back in 2001: “I’d like to take a second here to commemorate an anniversary that’s coming up tomorrow; it’ll be the anniversary of the first shift ever for ROBO in the MCC…”

Fast-forward five more years to 2021 and Kopra, now retired from NASA, has joined MDA as Vice President of Robotics and Space Operations.

The evolutionary thread that began in the 1970s with the Canadarm design for the Space Shuttle and traced through 20 years of Canadarm2 operations on the ISS is now extending into the future.

Canada was the first country to announce its partnership with the US in the Lunar Gateway, and will provide a next-generation robotics system known as Canadarm3. The CSA, again working with MDA, is defining the requirements based on the lessons and experience of the ISS. This, combined with 21st century technology, will send Canadian space robotics much further from Earth and enable them in ways unimaginable when the original Canadarm was being conceived.

About the author

Tim Braithwaite manages the Canadian Space Agency’s Liaison Office at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. In this role, he acts as the principal in-person point of contact between the Canadian Space Agency and NASA International Space Station (ISS) and Gateway programmes. Tim started his career at Spar Aerospace in Toronto, working on the design of the Canadarm2. He joined the Canadian Space Agency and moved to Houston in November 1995, where he led the establishment of the Canadian-US ISS robotics flight control team. In March 2001, he became the first ISS Robotics Operations Officer (‘ROBO’) to be certified to work in NASA’s Mission Control Center.