In the pre-dawn hours of 24 September 2014, there was hectic activity coupled with an air of excitement and nervous apprehension in the mission operations complex at Bengaluru’s high-security Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network.

Scientists and hundreds of media representatives were frisked and checked by the police while entering the complex. After clearing this hurdle, the media were taken to a large conference hall from where it had an uninterrupted view of giant screens in the adjoining room. The screens were flashing the same data as those in the nearby mission operations complex, known as MOX-2 – the command and control centre for the Mars operations.

The Mars team, many of them in their early twenties, clad in jeans and t-shirts, full of excitement, energy and enthusiasm, had been living in this place for the last few days. They were glued to their computers, monitoring data, now and then exchanging a word or two. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was present to witness the important event about to take place and top ISRO scientists and engineers were in another section, focusing their attention entirely on their computers.

The mood became increasingly tense as the historic moment neared. The minutes ticked by and when the screens flashed to indicate the burn of the spacecraft’s 440 Newton liquid apogee motor had started, the team clapped and cheered – an important milestone had been reached.

A satisfactory test of the engine had been carried out 48 hours earlier, giving the team a degree of confidence that all would go well on the big day. If this test had failed, an alternative method (Plan B) would have been activated, which meant using only the spacecraft’s eight 22 Newton thrusters. However, as ISRO chairman Koppillil Radhakrishnan put it, this would merely have been a “salvaging exercise”.

Then, at 7.42 a.m. (IST) the long-awaited magic number – 1099.98 – flashed up on a screen, setting off an enormous round of applause in the control room. 1099.98 metres per second meant that the spacecraft had attained the correct velocity. The critical and nerve-wracking Mars orbit insertion (MOI) had been successful. The 24-minute burn of the motor had been executed flawlessly using Plan A. The team had spent agonising days and sleepless nights waiting for this important signal, which was first picked up by NASA’s Canberra Deep Space Network.

The scientists and engineers were quick to exchange congratulatory handshakes and embraces and flashed the ‘V’ sign. Many were unable to control their emotions and briefly shed a tear or two. Prime Minister Modi shook hands with all the team members. India’s Mars Orbiter Mission, affectionately called MOM, had at once become the nation’s brand ambassador. In his much quoted nationwide address following the success from the Mars command centre, Modi said "MOM will never disappoint us."

India had made it to Mars on the very first attempt – when almost 75 per cent of global missions have failed

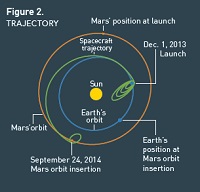

This mission, launched on 5 November 2013, at India’s vast spaceport Sriharikota near Chennai, had excited everyone, and millions across the country watched the developments on 24 September on TV. School children in the southern states of Tamilnadu and Kerala held programmes to celebrate India’s entry to the red planet. Congratulatory messages began to pour into ISRO offices from all over the world. A number of private companies made ads to sell their products using the image of MOM, such was its popularity.

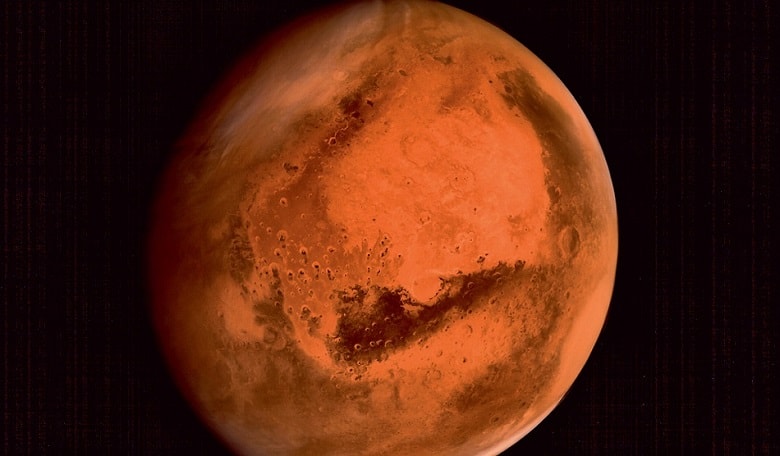

Yes, India had made it to Mars – and on the very first attempt – when almost 75 per cent of global missions to Mars had failed and the 25 per cent which were successful did not make it on the first try. India now became the fourth country to reach Mars after the US, Russia and the European Space Agency, catapulting it into the league of world space powers. In total, MOM had covered a distance of 680 million km.

International accolades

The mission, initially with a six-month life span, was essentially a technology demonstrator designed to establish that India had the capability to enter the Martian orbit. The next mission, which is being planned for 2018 with a lander and rover, is expected to have more scientific content. The first was a natural follow-up to India’s maiden mission to the moon, Chandrayaan-1 in 2008, which discovered water. The success of the lunar mission had given confidence to the Indian space community that it was capable of undertaking tougher and more challenging missions. Various options were evaluated and finally Mars became the natural choice.

S. Seetha, Programme Director at ISRO’s space science office, remarked: "The more missions to Mars, the more questions it throws up about the red planet. Science never ends. We have to find out what is not known."

The Mars Orbiter Mission spacecraft attached to the fourth stage of the PSLV-C25 rocket, awaiting closure of the heat shield

The Mars Orbiter Mission spacecraft attached to the fourth stage of the PSLV-C25 rocket, awaiting closure of the heat shield

With this triumph, which won international accolades, including one from Pakistan’s nuclear weapon scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan (a known critic of India) and another from China, India had excelled on several counts:

(a) It was the first country to have succeeded in the very first attempt.

(b) It was a solo effort - the European Space Agency’s Mars Express involved the teamwork of 17 nations.

(c) India accomplished this complex mission in just 15 months, compared to five or more years by NASA and other space agencies.

(d) India achieved it on a low budget – just $74 million dollars (Rs 450 crores.) Compare this to the cost of the film ‘Gravity’, which cost $100 million, and the price of NASA’s most recent mission to Mars, MAVEN, of $671 million.

What intrigued the international scientific communities, especially the space agencies, was how India had pulled it off at such a low price, even though it was a newcomer to Mars missions?

First, the rocket used for this record-breaking mission already existed – the proven four-stage Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV). The use of this launcher, however, imposed weight constraints, reducing the total mass of the five payloads to 15 kg. The original plan was to have nine instruments weighing 25 kg in total, if the rocket had been the three-stage Geo-Synchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV), which is capable of carrying more weight. However, there was some uncertainty regarding GSLV’s performance, resulting in it being replaced by the PSLV.

Second, only home grown components were used for the spacecraft, which went a long way to cutting down costs. For example, critical items like the attitude control, the gyro, a sensor and the star tracker were similar to those used in other Indian space missions.

Third, expensive ground tests were reduced. To minimise the costs, ISRO did away with the idea of building many models, such as a qualification model, an engineering model and a flight spare. It went straight to a flight model, which flew to Mars. Most importantly, it cut costs without compromising the safety of the mission and this was proved in no small way – perhaps setting a global trend for future Mars missions.

Fourth, personnel costs were low. In the words of the director of the Houston-based Rice Space Institute, David Alexander, space engineers cost much less in India than they do in the US.

Roddam Narasimha, a leading Indian aerospace scientist, in an interview with the New York Times, described the Mars mission as “a triumph of low-cost engineering”.

Future collaboration

Significantly, ISRO was in ‘go’ mode for this mission, even prior to the government giving the green light, which explains why it was possible to accomplish it in just 15 months. Although government approval was not granted until 3 August 2012, a Mars Mission Study Team had been formed in August 2010 (which endorsed the programme) and ISRO had taken delivery of the spacecraft from Hindustan Aeronautics Limited on 25 June 2012 and had already begun working on it.

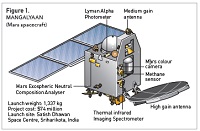

Likewise, the design and fabrication of the five payloads had also been initiated. The five payloads were:

(1) Lyman Alpha Photometer – studying the escape process of the Martian upper atmosphere.

(2) Methane Sensor For Mars – focusing on detecting the presence of methane.

(3) The Mars Exospheric Neutral Composition Analyser (MENCA) – analysing the neutral composition of the Martian upper atmosphere.

(4) The Mars Colour Camera - capable of capturing high-resolution pictures of the planet in a single image. Most other missions have had to stitch together multiple pictures to create a complete image.

(5) The Thermal Infrared Imaging Spectrometer – mapping the surface composition and mineralogy of Mars.

While the camera was switched on much earlier, the other four instruments were activated immediately after the Mars orbit insertion. The data is being downloaded at the Indian Space Science Data Centre at Byalalu near Bengalaru and is being transmitted to the principal investigators for analysis.

Geopolitically, the success of the Mars mission now allows India to stand shoulder to shoulder with other powerful nations at international forums such as the UN.

The success of the Mars mission now allows India to stand shoulder to shoulder with other powerful nations

Space experts feel that this low-cost mission could open the door to lucrative space deals with the US and Europe. This seems to be borne out by the fact that a few days after India entered Mars’s orbit, Prime Minister Modi and US President Barack Obama announced a joint mission to Mars. Even before this, India and the US had decided to set up a joint Mars mission working group.

This newly-formed group will explore how ISRO and NASA scientists can join forces to analyse data generated by both MOM and MAVEN missions. This will be mainly in the area of atmospheric research relating to Mars.

The launch of PSLV-C25 from Satish Dhawan Space Centre, Sriharikota on 5 November 2013, carrying the Mars Orbiter Mission

The launch of PSLV-C25 from Satish Dhawan Space Centre, Sriharikota on 5 November 2013, carrying the Mars Orbiter Mission

This apart, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Pasadena in California provided back-up support to track MOM through its deep-space networks at Goldstone in California, Madrid in Spain and Canberra in Australia. MOM Project Director Subbiah Arunan had earlier stated that nearly 250 NASA staffers at the three deep-space networks had been earmarked specially to monitor MOM’s Mars orbit insertion on 24 September. “Such is the high level of collaboration between India and the US in the space sector,’’ Arunan said.

The Mars mission has given a boost to India’s scientific sector and inspired youngsters to take science, technology, engineering and mathematics

The Mars mission has given a boost to India’s scientific sector and inspired youngsters to take science, technology, engineering and mathematics. In fact, it is said that after India became a member of the elite global Martian club, ISRO was flooded with applications from young scientists and engineers who wanted to join the space agency.

Further missions

Following the successful and historic rendezvous with the red planet, ISRO’s next goal is to test-fly an advanced version of the GSLV, designated GSLV Mark 3, which, once it becomes operational, will have the capacity to place in orbit four-tonne class communication satellites. This flight, which is provisionally slated for December 2014, will also evaluate the performance of the crew module during re-entry, which is part of India’s human space-flight programme. The current version of the GSLV can carry only two-tonne class communication satellites. Those with a higher mass have to be launched by Arianespace’s Ariane-5 rocket from the European spaceport of Kourou in French Guyana.

Thereafter, there are any number of missions relating to remote sensing and communication and the next major flight is expected in 2017, with the launch of the second mission to the moon, Chandrayaan-2, with a lander and rover.

As a whole, India has benefited from its space programme, especially in fields such as education, health, disaster warning, coastal management, mapping and agriculture. Thanks to the space programme and its Indian National Satellite Programme (Insat) almost every house today, including those located in remote areas, has a TV.

And of course, one should not forget the mobile telephone services which again are the result of the space age. A poor hawker on the road may not have a house but may well possess a mobile phone.

The PSLV, the work horse of ISRO, is in great demand by foreign countries to launch their satellites. This vehicle has so far carried about 40 foreign satellites (under a commercial agreement with Antrix Corporation, the business arm of ISRO) and 30 indigenous ones. This 44.4 metre tall rocket has logged nearly 25 successful launches since its maiden mission on 20 September 1993.