In the year 2000, writer, scientist and prophet, Sir Arthur C. Clarke sent a fax to an unknown inventor who had created an odd and innovative aircraft wing. Clarke complimented the inventor, Pat Peebles, and included a quotation from Clarke’s own ‘Laws’: Every new and revolutionary idea goes through four stages, which may be summed up by the following reactions:

1. What a stupid idea! Don’t waste my time.

2. Well, there may be something in it - but it’s not useful for anything

3. I said it was a good idea all along

4. I thought of it first The letter was a reassurance, a prediction and a warning.

The quote was to become what Peebles calls ‘a sort of template’ for his own experience as he continued to take the project forward to commercialisation.

What a stupid idea

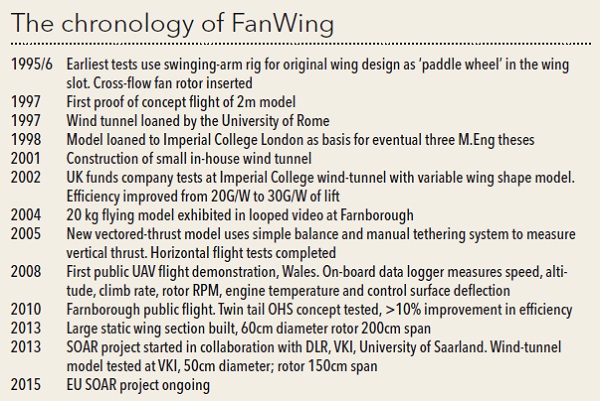

The FanWing company was officially incorporated in 1999. However, the story of the new wing had begun several years before. Peebles, a lifetime hobby tinkerer with an eclectic history of odd inventions, had long nursed a private dream of creating a new kind of rotor-powered flight. There were already experiments worldwide within his area of interest. Some of the aircraft took off but it seemed from the records that nothing sustained flight. Peebles thought he was as well qualified as any other eccentric inventor with a dream, and decided to have a try himself.

Money was short but private letters and emails from international figures in the aerospace world represented a form of moral capital.

He appeared to be the classic crazy night-time inventor with a non-flying flying machine and a day job. Then, his so-far 100% failure rate led finally to a test on a disused country road. Watched by family, a friend with a camera and two stray dogs, Peebles turned on the remote control for his latest experiment. And this time the little workshop prototype, maybe more resembling a mini grass cutter than an aircraft, took off and flew for a few seconds. Not an impressively long flight perhaps but it was a crucial turning point. For those few seconds of flight were the first proof of concept of what the New York Times would later describe as ‘one of the few truly new aircraft since the Wright Brothers’.

The innovation is apparently quite simple. It incorporates a system of fan blades within the wing. The aircraft has a normal fuselage and a motor that powers the rotors, which are contained within the open wings. The rotors take in air in front and eject it behind. Peebles’ goal was to spread the propulsion as far over the wing as possible. He had tried every kind of variation and finally this one not only worked but seemed, according to patent searches, to be new. Acceleration of the air over the wing results in both short take-off and heavy lift capability.

Pat Peebles at the SOAR wind tunnel, von Karman Institute.

Pat Peebles at the SOAR wind tunnel, von Karman Institute.

The media were the first to take up the story, along with a group of friends and family who covered initial patent costs for the newly-formed FanWing company. Establishment response was more sceptical and Peebles now thinks that he was naive in assuming that a new way to fly would be exciting to Money was short but private letters and emails from international figures in the aerospace world represented a form of moral capital. everyone. He hadn’t taken into account how arrogant the whole thing would appear. The aircraft looks odd and amateurish, and the provenance was, as Peebles says himself, ‘a self-educated nobody from nowhere.’ He realises now that from the outside it would have been almost impossible to take the invention seriously. However, background professional support did start to consolidate.

Money was short but private letters and emails from international figures in the aerospace world represented a form of moral capital. Then in 1998 one establishment figure provided a new turning point for the invention.

Turning point

Professor JMR Graham, then Head of Unsteady Aeronautics at Imperial College, London, asked Peebles to authorise his own departmental use of the wing as the basis for a graduate thesis because as he said, “Many have tried but this one worked.” There followed a series of three graduate papers each based on studies of the early model wing Peebles lent to the college.

Credibility grew. A Royal Aeronautical Society UK branch invited the company to present a guest lecture attended by the Society’s Chief Executive. Professor David Nicholas, UK Government advisor and dedicated defender of inventors, championed the company, and FanWing Ltd. won three grants. The BBC and Discovery Channel filmed the aircraft, Newsweek picked up the story in a major spread and the company, maybe with more bravura than experience, set up its wares at Farnborough Airshow.

Professional as well as media and investment interest took off, raised further by Peebles winning second prize in the International Saatchi & Saatchi ‘World Changing Ideas’ Award. The New York Times listed it in 2004 as one of the year’s best inventions. A journalist from the Royal Aeronautical Society’s journal, now its editor, wrote a detailed analysis of the whole project, comparing it favourably to the helicopter and entitled it: “Revolution in the Air”.

Interest was added by the fast-growing general commercial interest in the then new unmanned aircraft market. UAVs/drones seemed particularly suited to the FanWing technology. Peebles was approached for discussion of ‘potential collaboration’ in turn by Boeing, British Aerospace, and Lockheed Martin. The Hungarian Government Defence University lectured on the technology and a Swiss company offered partnership.

The Russian version of the magazine Popular Mechanics ran a long article and Gazprom emailed for more information. A several-day meeting in China resulted in an invitation to set up a development programme, and the company was invited to meetings with both Arab and Israeli organisations. However, despite all the overtures, the company was struggling.

An artist’s impression of a FanWing cargo carrier.

An artist’s impression of a FanWing cargo carrier.

Unable to afford professional management, it passed due diligence but was amateurish in presentation, and the technology was still neither professionally tested nor documented. Additionally off-putting, the company was basically a husbandand- wife partnership, with one other US director - or as a major organisation put it, ‘a mom-and-pop garage outfit’. One leading UK aerospace assessment company later fatally summed up the FanWing for one top-level investment negotiation: “It looks funny.” Crucially, while the Imperial College papers had maybe conferred professional credibility on the invention they had also removed it. For one of their academic conclusions claimed that the aircraft, while taking off almost immediately and with a heavy load capability, would never hit more than bicycle speed.

The FanWing had now it seemed reached the second stage originally described by Clarke: It may be interesting but it’s not useful for anything.

Cherish your gains

However, Peebles was learning to cherish his gains. It was after all, he said: ‘a new way to fly. That couldn’t be all bad’. The company had attracted private investors in several countries and a talented aerospace artist for projected images. There was a growing team of strong commercial representatives. There was less obvious support too. A national UK newspaper and some top-level aerospace experts had expressed public or private excitement with the invention and a growing impatience with the UK, which they said seemed about to continue its record of losing major inventions.

And there were other pluses. Patents issued internationally had proved that the FanWing was unique. There were proven advantages in its almost instant take-off and landing on unprepared ground, fuel efficiency, heavy lift, manoeuvrable operation and no stall. Potential commercial applications ranged from security surveillance, disaster aid, minesweeping and fire watch to crop dusting and cargo lifting. The company possessed filmed proof of concept in the form of a series of successfully scaled flying model prototypes. And it had the invaluable and ongoing interest of a group of top-level journalists both in and out of the aerospace world.

Nevertheless, it was increasingly obvious now that in order to gain any further backing, the company needed not only better management and presentation: professional testing and academic analysis were more and more obviously the only way to breach the walls of the established aerospace world. As Sikorsky designer and former vice president of research Ken Rosen succinctly put it to Peebles: ‘You need the science.’

The project went into decline. The company had to survive on mainly free labour and the generosity of their long-suffering investors. But there was nothing left after patent and basic running costs to cover the level of management, PR, and the professional documentation that was badly needed to attract more investment. It was Catch-22.

However, there were good surprises as well as setbacks. The next turning point was an approach by a UK engineer. George Seyfang had formerly been responsible for assessment of New Concepts for BAE Systems and was part of the team that had previously rejected the FanWing. He had taken early retirement and was now engaged in what he called ‘hobby’ projects and he suggested to Peebles an experiment. He saw the FanWing as particularly suited to the ‘Outboard Horizontal Stabiliser’ concept - OHS is based on observation of flocks of migrating birds where each bird in the V formation receives lift from the wing tip of the bird in front.

The suggestion was what Peebles calls a lightbulb moment. He was already booked to fly his original model at the 2010 Farnborough Airshow and met Seyfang there. Immediately after the demonstration he made a first flying experiment with the new concept. The potential improvement in efficiency was immediate and obvious.

Seyfang re-investigated the basic technology. As a professional sceptic with over forty years’ experience of assessment of major aircraft, he tunnel-tested the wing independently over several months. He concluded this time round that the FanWing had a convincing commercial future, specifically in shorthaul heavy-lifting cargo transport. He and Peebles set up an informal technical partnership to develop the new twin-tailed FanWing.

The first flight of the first FanWing model.

The first flight of the first FanWing model.

Still ‘looked funny’

It was still a workshop development Seyfang called a hobby project and it still ‘looked funny’. However, Seyfang had brought to the company a new level of credibility and technical input. He was also now publicly presenting at international conferences his own conviction that the FanWing would with the right development present advantages in speed (the previous bicycle prediction had been long disproved), heavy-lift, forward flight efficiency and in lower noise output that would challenge the helicopter.

Then in 2013 via the European Union, the ‘science’ suddenly started to arrive as a full package. Peebles had been producing promising efficiency results with Seyfang on a newly upscaled static wing when he was unexpectedly invited by a leading Russian aerospace professional to attend a meeting in Brussels. The discussion included a potential and small addition of the FanWing technology to a large European group project. Following Peebles’ presentation, an American research engineer at a German university, among others, approached him for more information. Finally a group of three organisations together with the FanWing company then presented to the EU a new proposal described neutrally as ‘an Open-Fan Wing Concept’. Several months later the team’s project SOAR won a twoyear research award. And that’s where the company stands now.

Fanwing’s future

The project is led by DLR, the German Space and Aerospace Research Centre; the team has conducted preliminary wind-tunnel tests and computational fluid dynamics simulations at the Belgian von Karman Institute, and the University of Saarland led by engineer Chris May has provided the wing motor and actuation mechanisms.

He concluded this time round that the FanWing had a convincing commercial future, specifically in shorthaul heavylifting cargo transport.

Test results are yet to be fully assessed and documented. Peebles says: “It’s open ended and we’re not sure yet where we’re headed, whether towards upscaled cargo lifters or smaller drones. But for the first time the technology is being investigated, documented and finally being taken seriously by some of the world’s top research organisations.”

From a small ‘funny looking’ model taking off in the middle of nowhere to an EU-funded team enterprise, Clarke’s Law may yet still apply, but there is no doubt that the concept has taken a major step forward.